Paired with a work by Stanford in Irish-themed evening

An edited and shortened version of this article appeared in the Boston Musical Intelligencer.

The Boston Globe had an exciting piece last week in anticipation of the performance of Beach’s “Gaelic” by the Mercury Orchestra on August 7. The Mercury Orchestra‘s performance of Beach’s monumental work emphasizes that the grass-roots momentum of recognizing Beach’s achievement continues to build. In anticipation of the concert I had a few more pertinent thoughts to share.

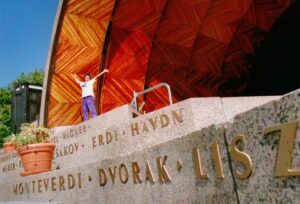

A local-history sidebar pertaining to the venue, the Hatch Shell: The Aug. 7 performance takes place 20 years after the announcement (June 22, 1999 in the Beacon Hill/Back Bay Chronicle) that the Metropolitan District Commission would add Beach’s name to the 87 composers’ names that decorate the that august structure. Announcements in the Globe and the Somerville Journal followed (illustration)

1999 photo, original caption: Music historian Liane Curtis successfully lobbied to have composer Amy Beach’s name added to the Hatch Shell. Photo credit: Winslow Martin, Somerville Journal

and the addition of Beach’s name was unveiled on July 8, 2000, in a concert of the Boston Pops, directed by Keith Lockhart. It was a fun and tangible step in bringing deserved recognition to this remarkable composer. The detailed story of changing that iconic “writing on the wall” is here. (because of impending rain, the concert has been moved to NEC’s Jordan Hall).

Because Beach’s Symphony includes Irish tunes, it is sometimes assumed that she was Irish — for instance, this 2017 review of the Landmark’s Orchestra performing the scherzo of the “Gaelic” Symphony erroneously states that she was part of Boston’s Irish-American community! Such a remark shows ignorance about Beach’s social role and the status of the Irish community of that time, that faced considerable prejudice and hostility. While she had some distant Irish heritage, both sides of her family had been in the U.S. since the 18th century or earlier. She had married up into Boston’s elite class, and for her to empathize with the Irish refugees and immigrants was to take a stance discouraged by her circle; musicologist Sarah Gerk suggests that anti-Irish sentiment was the source of some of the (few) negative reviews that her Symphony did receive. That Beach would step across class boundaries to express compassion for these immigrants is a topic that is especially relevant when issues of migration and refugees are in the news daily.

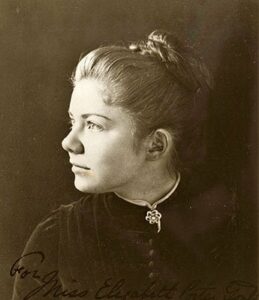

Amy Beach, ca.1887.

Photo by Baldwin Coolidge

Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy (of which I am the President) produced a new edition of Beach’s “Gaelic” Symphony in honor of Beach’s 150th birthday anniversary in 2017. We are thrilled to have helped many dozens of performances take place using these materials, newly edited and engraved by Chris A. Trotman, M.M./M.L.I.S.. (More information about the edition here) In the anniversary season of 2017 and 2018 a wide range of orchestras, from Maine to California, from Anchorage AK to Albany GA, student and community ensembles, and a wide range of professional groups. Wide, but missing that highest echelon: the top tier of U.S. orchestras. David Weininger’s Globe article mentions that the possibility of anti-American bias (discussed extensively in Douglas Shadle’s book) has influenced Beach’s legacy, along with ingrained sexism. Indeed, implicit bias is perhaps more a problem among the highest ranking orchestras. Andris Nelsons, with his eastern European upbringing and training – and continued focus – obviously knows little about American music in general, and is clueless about Beach. He is too busy bringing us the worst of Shostakovich’s Symphonies (in 2006 I heard Valery Gergiev state there was really no reason to waste time with Shostakovich’s 2nd). BSO Artistic Admin Anthony Fogg seems to think that Beach is a mere local novelty, not the major figure on the international stage that she was in her own era and is becoming again now. At the highest level of artistic planning these are men (still almost always men) who think that what they know is always right. There might be music – new music – to learn about, but you can’t tell them they need to learn something new about the late 19th century symphony. That would entail admitting they had been wrong in the past!

The leaders and planners of other orchestras are more open to human curiosity and to admitting the possibility of their own fallibility, more likely to say “there just may be some music written decades ago that I don’t know now that is worth considering.” Thus the revival of Beach’s works for large ensembles has come through open-minded artistic leadership, listening to the enthusiasm of their audiences and musicians, and exploring off the beaten path of the inscribed canon. We hope this interest is now beginning to “trickle up” – In April, the Minnesota Orchestra – one of the top-10 U.S. ensembles — performed Beach’s Symphony This is a real break-through! And performances by other ensembles continue, from Boston’s own Eureka Ensemble in 2018 (you can listen here) to the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, and many more. To my mind this shows a grass-roots growth of interest. Dedicated musicians who are in the trenches of everyday music-making are building an enduring fan-base for Beach’s orchestral music. That the Boston Symphony will be the last to notice Beach’s music reveals their arrogance and implicit bias.

Charles Villiers Stanford is perhaps best known as the teacher of Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst and Rebecca Clarke, and for some Anglican Hymns. A prolific composer, his music is a rarity, especially in the U.S. His choral-orchestral ballad Phaudrig Crohoore also was premiered the same year as Beach’s Symphony, 1896, at the Norwich Festival (in the UK).

Stanford, c. 1894

With a lively narrative text by J. Sheridan Le Fanu, its protagonist is a bold, craggy Irishman with a heart of gold. Those who would like a preview can listen here (a section of the text is also included). Stanford’s biographer, Jeremey Dibble, suggests that because of the “mannered colloquial … ‘stage Irish’ text” the choral ballad is rarely performed, and Wednesday’s performance will be one of the first in the U.S. since the early 20th century. The performance history is detailed here (pdf). It observes that for some Victorian choristers, the use of the word “divil” and a reference to possibly licentious behavior on the part of the hero made the text unsingable, and resulted in the choral work’s censorship. The poem, however, was popular and widely known from public readings, so this was a frustration for Stanford and his advocates.

Thanks to the Mercury Orchestra for their inspired programming, and I am glad that the show will go in the beautiful Jordan Hall.