By Sarah Baer

Our favorite spring tradition at Women‘s Philharmonic Advocacy is collecting the season announcements from America‘s top orchestras. This process, which is always full of trepidation and hope as we gather data that indicates the direction of classical music programming in the United States, is extensive. Which makes it all the more heartbreaking when the results demonstrate how little progress has been made. As I‘ve mentioned before, the tumultuous events of recent years – #MeToo, pandemic programming, the first glimmers of larger institutions reckoning with the history of white supremacy that dominates classical music programming – have offered many opportunities for organizations to have thoughtful internal conversations and decision making processes, to make conscious choices and to opt in to the change that is so desperately needed in order for these ensembles to do more than merely survive in the coming years. As we look at the data compiled from the just-announced 2024-2025 season, particularly in year-over-year comparisons with past seasons, the possibility for a more equitable future, sadly, seems further out of reach than before.

An explanation of our methodology:

As in years past, I looked at the top 21 ensembles in the United States (as ranked by annual budgets) and looked specifically at the works that they programmed for their primary subscription series. Any concerts labeled as Family, Holiday, Pops, or other special events not included in typical subscription packages were omitted. The goal is to look at what a typical concert season includes and sells to the largest portion of their audiences. While several ensembles have exciting chamber music, “new music,” or family programming including works by women, as these events are “special events” and not heard by a majority of the listening audience, they are not included in the data.

All of the information was taken from official press releases, concert calendars, and ensemble websites and was accurate at the time of this writing – and with full understanding that programming can change for various reasons throughout the season.

Now, for the numbers.

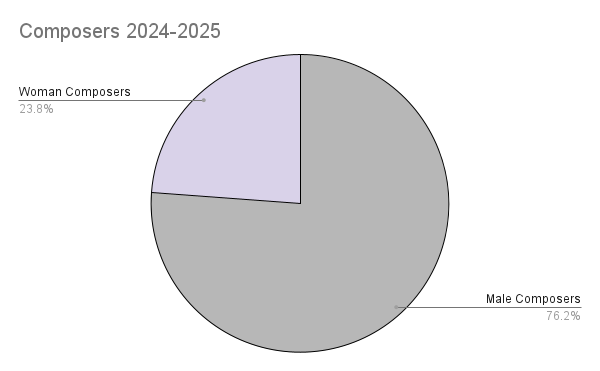

Throughout the coming season, the combination of all 21 ensembles will feature music by 281 different composers. Of those, 67 identify as women – a total of 23.8%, and a full percentage point more than in the 2023-2024 season. There is a discernible trend of agonizing slow progress, but progress nonetheless.

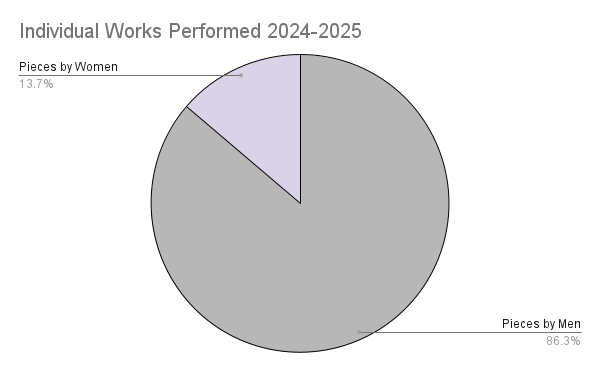

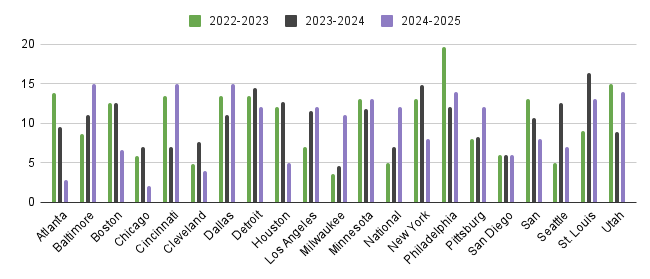

Among the ensembles there are 874 individual works being performed, with 121 pieces having been written by women – 13.7%. In the 2023-2024 season pieces by women made up only 7.8% of programming, so on its face, this appears to be significant gains. It’s less encouraging when we factor in that in 2022-2023 pieces by women made up 14.1% of total programming.

However, and as always, the most telling figure is the relationship of the number of works to individual performances. For example, each of Beethoven’s symphonies counts as an individual work (i.e.: Symphony No. 3 counts as one work) and the individual performances are how many times it is heard across the various ensembles during the season (in the 2024-2025 season, Beethoven‘s Symphony No. 3 will be performed by ten of the ensembles). Note: when collecting data I only looked at what was programmed, not how many individual performances are given by each ensemble. Some ensembles perform the same program two or three times to accommodate their subscribers, but it is still accounted for only once in the programming data.

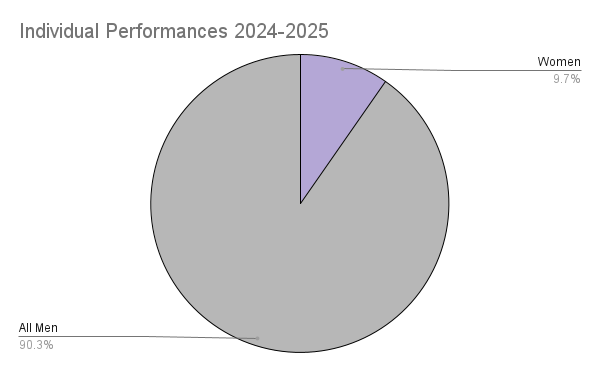

Of the 1448 individual performances of works planned for the coming season, 141 of the performances are of works by women: 9.7% of the total, and less than the 10.5% of the total that women‘s works saw last season. This is the latest data point in a consistent downward trend: 2022-2023 heard works by women performed 10.7% of the time, and 2021-2022 shared works by women 11.9% of the time.

As I mentioned last year: whatever forward momentum that was gained over the past several years, the opportunity for meaningful self-evaluation and change, is now quickly backsliding into how things used to be. These ensembles, those with the highest operating budgets in the country, and with the most to gain and least to lose by incorporating new programming and leading the charge in real change, have demonstrated that their supposed commitment to performing works by women was an opportunistic publicity grab. While they are happy to perform works by women when it suits them, there is no larger impetus for larger, systemic changes.

Something that is far harder to calculate, but should be noted, is the actual time spent performing/listening to works by women versus men in any given concert, as well as throughout the season. Without knowing the running time of each of the 874 individual works being heard (some of which are new commissions, or works by women that have never been recorded), it‘s impossible to calculate. But consider that the most performed work by a male composer this coming season is Brahms Violin Concerto (being performed by 12 ensembles) with an average running time of about 42 minutes. In contrast, the most performed work by a woman composer is Florence Price‘s Violin Concerto No. 2 (being performed by five ensembles) with an average run time of 15 minutes. The second most performed work by a woman is Sofia Gubaidulina‘s Fairytale Poem (being performed three times), which has an average run time of 12 minutes. The second most performed work by a male composer is Beethoven‘s Symphony No. 3 (will be heard 10 times this season) with an average run time of between 41 and 56 minutes.

The point being, while women‘s works are being included, they are rarely the featured work. They are rarely even discussed in the season program blurb about the concert itself. It‘s a convenient addition to round out the concert, while also being a performative nod to us – those squeaky wheels who are calling for change that the large organizations never intend on actually making. The inclusion of many of these works is clearly performative and done from a point of pressure, not by ensembles embracing the changes that need to occur for the industry to continue on in any meaningful way.

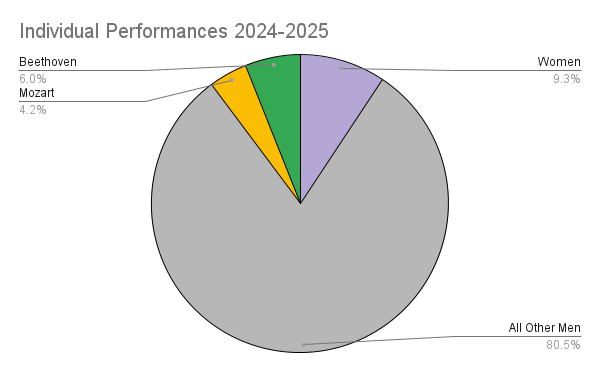

As some proverbial food for thought, the combined performances of works by just two composers (Beethoven at 90 performances, and Mozart at 63) equal 12 more performances than all of the works by women combined (141). Even this is a point of disappointment – last year the combined performances of Ludwig and Wolfie were three fewer than the combined performances of all works by women. WE ARE MOVING BACKWARDS.

And, as has been the case since we at WPA have started looking at this data, it is primarily works by dead men and living women that are heard. While contemporary women – who are actively winning awards, advocating to have their works heard, and networking throughout the industry – receive a significantly higher percentage of performances, it is always exciting to see when historical composers are also included. In the coming season these include:

Elfrida Andrée

Grażyna Bacewicz

Amy Beach

Margaret Bonds

Mel Bonis

Lili Boulanger

Louise Farrenc

Augusta Holmès

Dorothy Howell

Vítězslava Kaprálová

Leokadiya Kashperova

Alma Mahler

Julia Perry

Florence Price

Mary Lou Williams

When looking at individual ensembles, it is clearer to see where the commitment to diverse works are beginning to fade away, or maybe grow. In one instance, it’s clear to see where the limits of the organization’s commitments lie.

Eight Orchestras Increase their Programming of Works by Women

Of the 21 ensembles, only a few significantly increased the number of works by women programmed versus their performance calendar last year. In considering who was making actual progress I looked not only at the number of works performed, but the percentage of works performed over the course of the season. For example, playing five works by women composers when the season contains 50 individual works is more significant than playing five works by women composers when the season contains 75 individual works.

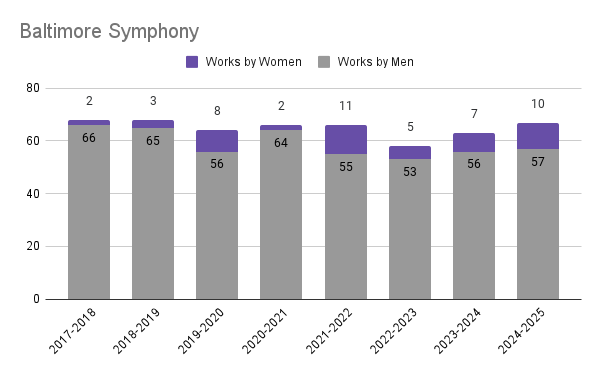

The Baltimore Symphony will be performing 10 works (vs. 7 in 2023-2024). In total, works by women composers make up 14.9% of their 2024-2025 programming. Their season includes works by historic (Louise Farrenc, Mary Lou Williams) as well as contemporary composers (Jessie Montgomery, Chen Yi, Anna Clyne).

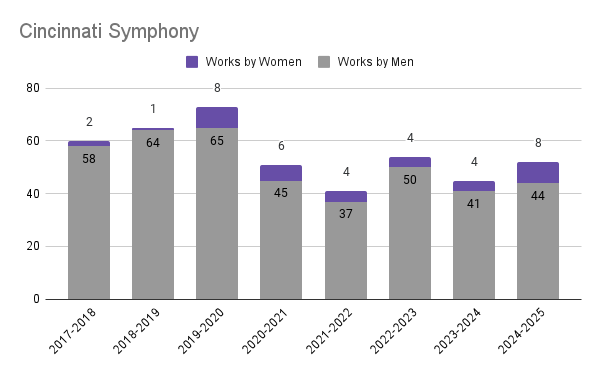

The Cincinnati Symphony doubled their representation of women from the prior season, from four works to eight, making performances by women composers from three works to scheduling eight works by women in the coming season, making performances by women 15.3% of their programming. Their season includes Florence Price, Wang Lu, Julia Perry, and Unsuk Chin.

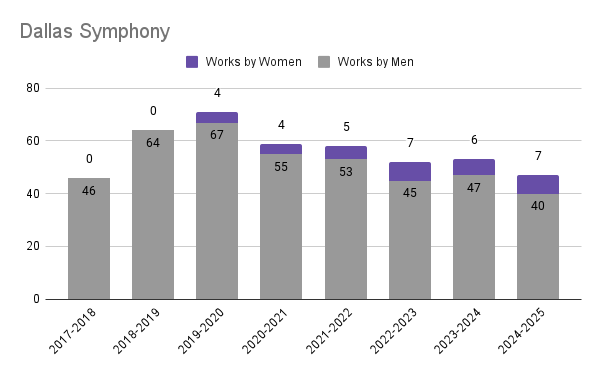

Dallas Symphony will perform seven works by women – a total of 14.89% of their relatively small season. They include works by Alisson Kruusmaa, Amy Beach, Hannah Eisendle, Sophia Jani, Arlene Sierra, Julia Perry, and Henriette Renie. It is encouraging that three of these seven works are by historic women, including Amy Beach’s monumental Piano Concerto op. 45.

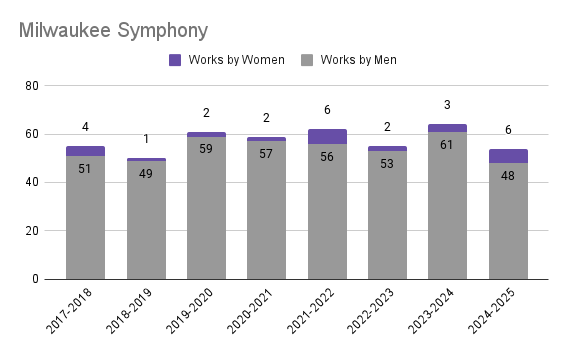

The Milwaukee Symphony also doubled their programming of works by women composers from the previous year, from three pieces in 2023-2024 to six pieces in 2024-2025, making compositions by women 11% of their programming. They are, in fact, opening their season with Dobrinka Tabakova‘s Orpheus‘ Comet. Other works throughout the season include pieces by Tania León, Anna Clyne, Jessie Montgomery, Lili Boulanger, and Clarice Assad.

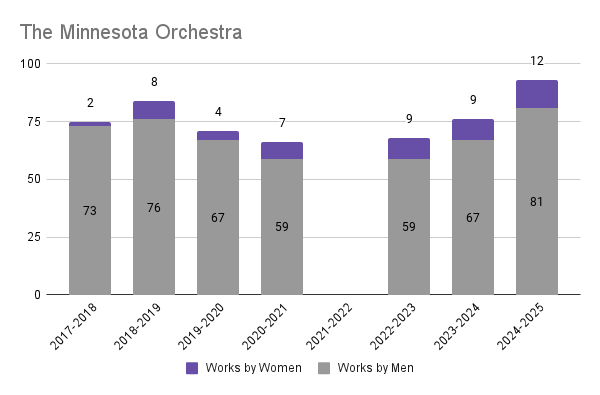

The Minnesota Orchestra is showing growth in many ways – increasing not only the number of works by women they included, but the total number of works in the season, as well. Women make up a total of 13% of the season, and include works by: Andrea Tarrodi, Unsuk Chin, Gabriela Ortiz, Betsy Jolas, Margaret Bonds, Elfrida Andrée, Outi Tarkiainen, Du Yun, Dorothy Howell, Dobrinka Tabakova, Grażyna Bacewicz, and Hannah Kendall.

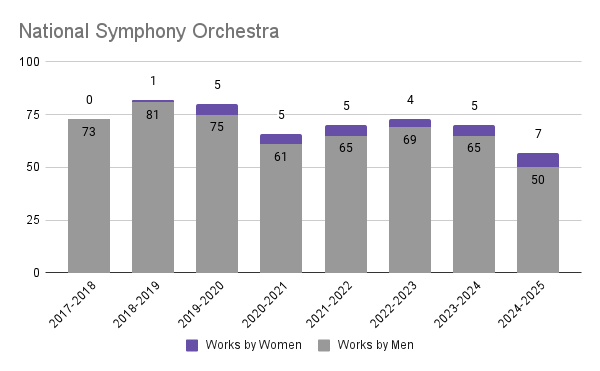

The National Symphony Orchestra will perform works by: Jessie Montgomery, Mel Bonis, Jennifer Higdon, Cindy McTee, Gabriela Ortiz, and Julia Wolfe. Works by women will make up 12% of their programming.

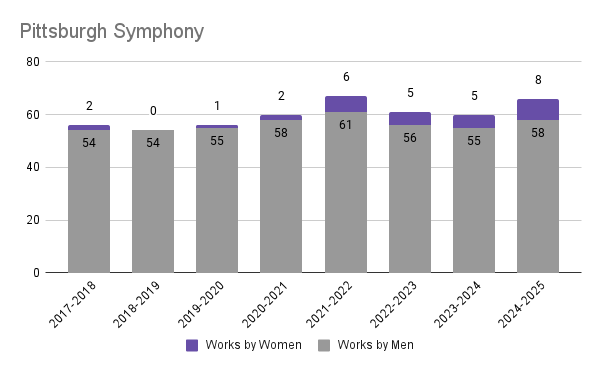

The Pittsburg Symphony also shows exciting growth in the coming season. Performing eight pieces in the 2024-2025 season, a total of 12% of their programming, this coming season also marks the most works by women that the ensemble has ever performed. They will include pieces by Reena Esmail, Maria Huld Markan Sigfusdottir, Hannah Ishizaki, Noriko Koide, Hannah Eisendle, Sophia Jani, Unsuk Chin, and Lera Auerbacher.

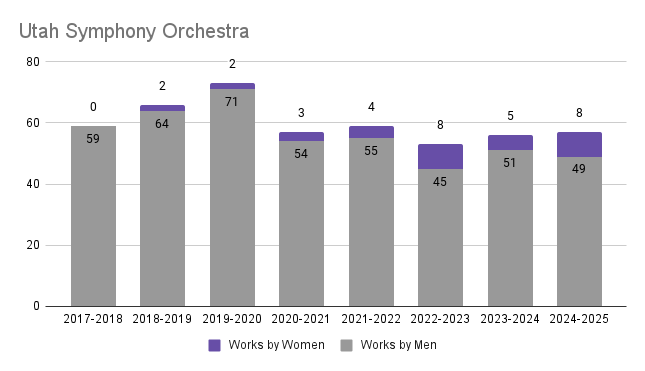

The Utah Symphony and Opera, which is another highly conservative organization, is providing a bit of optimism in their programming. Women are included in 14% of the 2024-2025 programming. Composers include: Dobrinka Tabakova, Jennifer Higdon, Gabriela Ortiz, Florence Price, Angel Lam, Elizabeth Ogonek, and Jessie Montgomery.

MOST ENSEMBLES DECREASE THEIR PROGRAMMING OF WOMEN

What is more striking – and concerning – are the numerous ensembles that significantly decreased their efforts in performing diverse and representative works in their concert program.

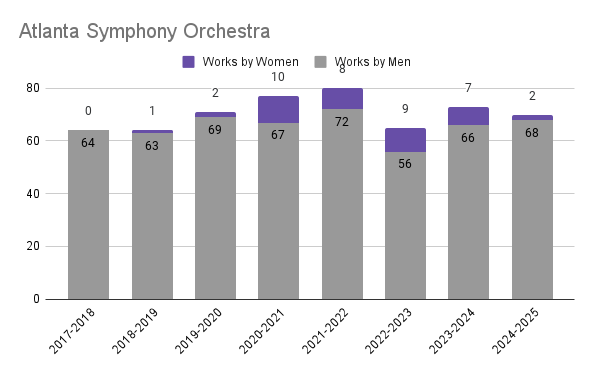

The Atlanta Symphony dropped from including women in 12.12% of their programming in 2023-2024 to including works by women in just 2.8% in 2024-2025. The two works that will be heard are Winter Bells by Polina Nazaykinskaya and Jennifer Higdon‘s Harp Concerto. But, no need to worry – they are including what they‘re calling the Beethoven Project in the coming season, with performances of all of his symphonies.

The Boston Symphony also significantly decreased their programming of works by women, with compositions by women composers making up only 6.66% of the 2024-2025 season. This is half the amount of the previous season (12.69%). They will perform works by Tania León, Hannah Kendall, Chen Yi, Gabriela Ortiz, and Aleksandra Vrebalov. Not to be outdone by Atlanta, Boston will also be performing the complete symphonies of Beethoven. Again.

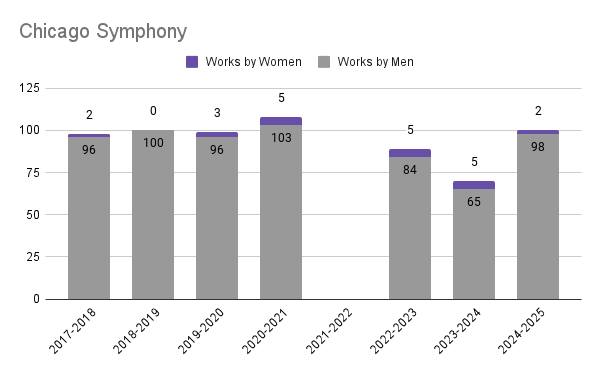

Chicago will have women incorporated in 2% of their programming for the coming season, performing exactly two works by women composers: Florence Price‘s Violin Concerto No. 2 and Sofia Gubaidulina‘s Fairytale Poem.

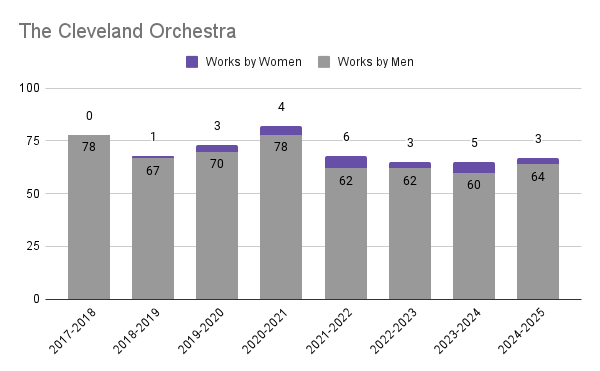

Cleveland is at least ahead of Chicago, with women making up a total of 4.4% off pieces programmed. The three compositions they are including this season are by Silvia Colasanti, Kaija Saariaho, and Allison Loggins-Hull. Cleveland is also performing all of Beethoven‘s Piano Concertos.

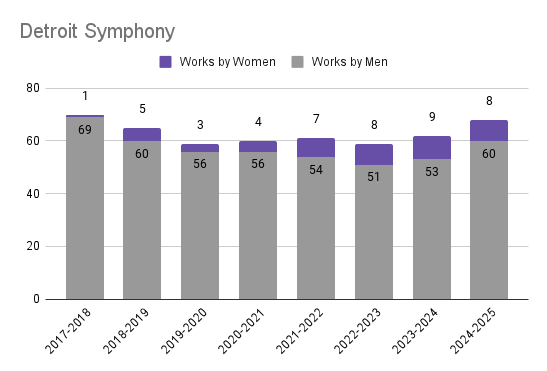

The Detroit Symphony will hear works by Joan Tower, Anna Clyne, Camille Pepin, Florence Price, Jessie Montgomery, and Leokadiya Kashperova. Works by women make up 11.76% of their programming.

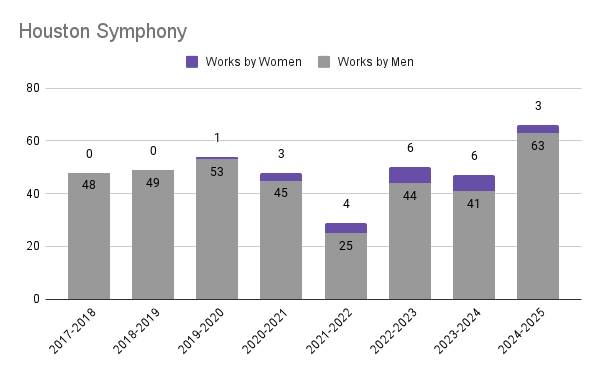

While there were a handful of ensembles that doubled their representation of women from the year prior, Houston decided to go the other route and cut theirs in half. The three works by women that will be heard in 2024-2025 are Vitezslava Kapralova‘s Military Sinfonietta, Anna Thorvaldsdottir‘s Metacosmos, and Unsuk Chin‘s Alice in Wonderland: Prelude to a Mad Tea Party. Works by women make up a total of only 4.76% of programming.

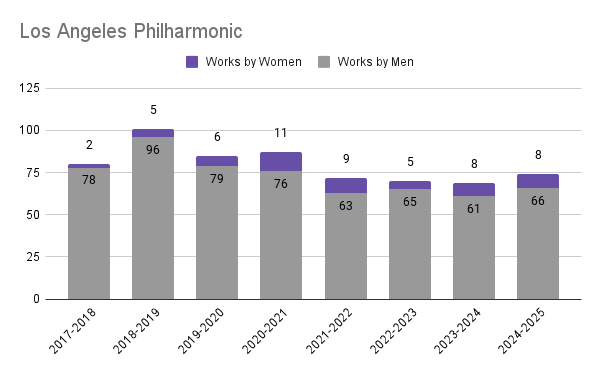

The Los Angeles Philharmonic decreased the programming by women slightly by keeping the same number of works by women, while growing the total works performed in the season.. Works by women will make up 10.8% of their programming in the coming season, and will include pieces by: Gabriela Ortiz, Kaija Saariaho, Grazyna Bacewicz, Alma Mahler, Florence Price, Julia Adolphe, and Caroline Shaw.

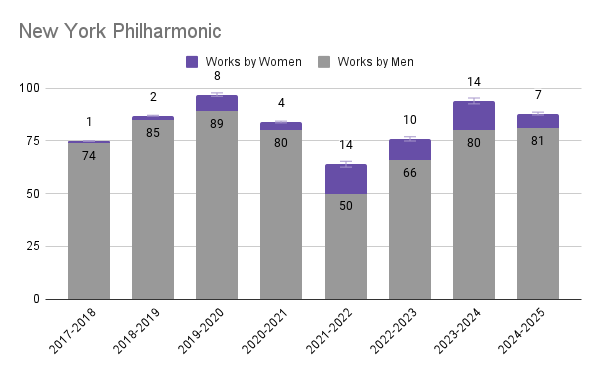

The New York Philharmonic decided to follow the same route as Houston and cut their programming of women composers in half. This is also likely due to the completion of performances tied to Project 19, the original timeline of which was altered due to the pandemic. With no more commitments to perform commissioned works, they are quickly slipping back to the status quo. The works by women heard in the coming season, which make up a total of 7.8% of the programming, are composed by: Augusta Read Thomas, Nathalie Joachim, Sofia Gubaidulina, Julia Wolfe, Gabriella Smith, Kaija Saariaho, and Kate Soper.

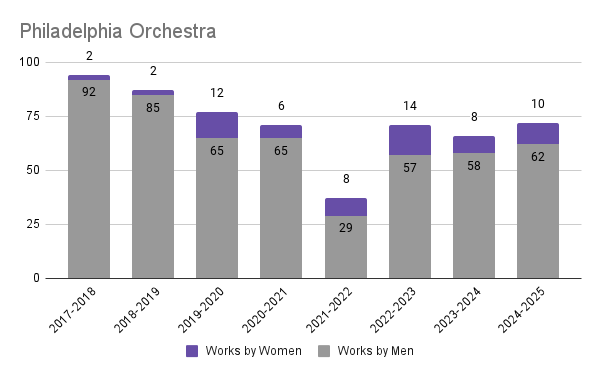

The Philadelphia Orchestra, while not yet returned to the great heights they achieved during the pandemic, is maintaining fairly decent attention on equitable programming, with women making up 13.8% of the programming in the coming season. While this is growth from the previous year (they performed 12% works by women composers), it pales in comparison to the almost 20% works by women they achieved in 2022-2023. They can do better, they just choose not to. In the coming season Philadelphia will perform works by: Betsy Jolas, Augusta Holmès, Margaret Bonds, Kaija Saariaho, Julia Wolfe, Louise Farrenc, Gabriela Lena Frank, Missy Mazzoli, Barbara Assiginaak, and Florence Price.

The San Diego Symphony, as is clearly demonstrated by the image above, has always been conservative when it comes to expanding their programming. The four works that they are including in the 2024-2025 season are by Unsuk Chin, Gabriella Smith, Augusta Holmès , and Anna Clyne. Women comprise 6.4% of the programming. While this is one piece more than the previous two years, and the most pieces by women composers that the ensemble has ever played in the years we’ve been keeping track, they continue to program women for no more than 6% of their programming.

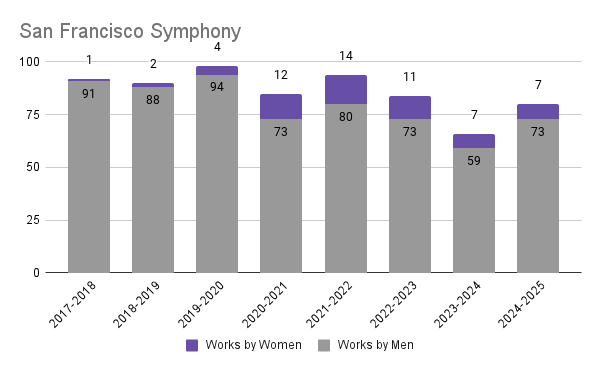

The San Francisco Symphony will include seven works by women composers in the coming season, a total of 8.75% of their programming. The composers that will be heard include: Missy Mazzoli, Gabriela Ortiz, Gabriela Montero, Joan Tower, Kaija Saariaho, Anna Thorvaldsdottir, and Gabriella Smith.

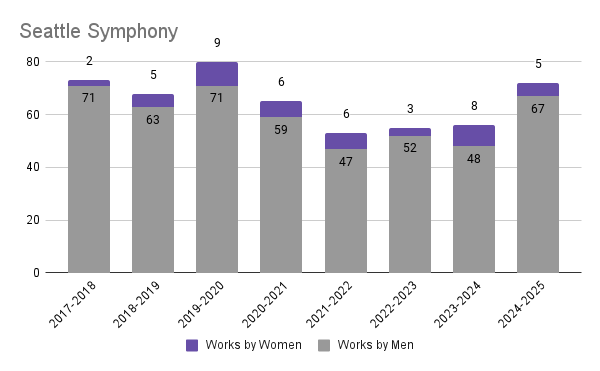

The Seattle Symphony has had its ups and downs in programming over the years – with wonderful work bringing forgotten pieces to light, but also years where it is clear that equitable programming fell from being a priority. The five works that will be heard in the coming season are by Angelia Negron, Kaija Saariaho, Lili Boulanger, Jennifer Higdon, and Allison Loggins-Hull. Works by women make up 6.94% of the season.

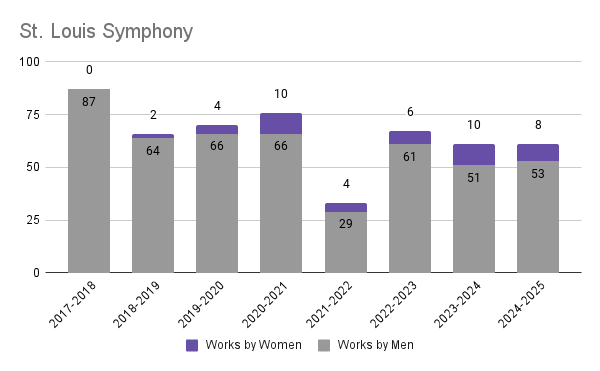

The St. Louis Symphony will include women in 13% of their programming, including works by Gabriela Lena Frank, Cindy McTee, Anna Clyne, Nina Shekhar, Outi Tarkiainen, Kaija Saariaho, and Grazyna Bacewicz.

THE BIG PICTURE

Though there are particular high (and low) spots throughout the different ensembles, looking at the big picture – a year over year comparison of the percentage of works by women composers that they have performed – it’s easier to see where the truth lies:

The momentum has vanished. Calls for change are now falling on deaf ears as arts administrators, board members, and high level donors are insisting that these ensembles move beyond what they consider to be fads and back to the status quo that is rooted in white supremacy and patriarchy. While there is some progress in the diversity of programming, we continue to return to The Canon in ways that will only contribute to the eventual demise of orchestral institutions. In the 2024-2025 season works will be heard by 281 composers. In the 2023-2024 season that number was 294. The answer is to hear more distinct voices, not fewer, and to hear more from those new voices. That there are two high powered and deeply influential orchestras who feel it is necessary to feature the complete performances of Beethoven’s symphonies in the coming season – works that any regular symphony attender could easily and heartily sing along with the orchestra, having heard them so often – is evidence enough of the brokenness of the system.

As mentioned above, the focus on these particular ensembles in each annual repertoire report is to highlight the work being done by the ensembles with the most power, privilege, resources, and influence in the larger classical music world. These are the ensembles that young musicians are aspiring to join one day, who have the financial backing to make recordings, who are held in the highest esteem. When these ensembles – our supposed “best of the best” – continue to fail so tremendously in making the changes that have long been called for, it’s easy to become beyond disheartened. Yet, as the work of the social justice movements have taught us, worthwhile change takes time and persistence on the part of those calling for that change.

So, what can we do?

Continue to call for change, in whatever way works best for you. Maybe a bullhorn would be helful, but one would think that enough politely worded emails to any organization sharing your disappointment in their lack of equity in programming will be hard to ignore.

Support the ensembles that are doing the work, that are performing the pieces that you want to hear. Many community and regional ensembles have fantastic programming that is worth supporting, likely even in your backyard. Look to our list of annual grant winners and other updates on our blog can help you to find an organization in your area.

Continue to educate yourself, and others, as to the vast amount of and value in the music that is still so underrepresented in concert halls. Advanced music education has widely failed students for decades, teaching little outside of the traditional Canon – which is based in white supremacy and patriarchy. Look outside of the music that we were told was inherently good and valuable and recognize that we need to experience a much wider range of music, so we can learn ourselves about these broad horizons. All music has inherent value – it represents a time and place, a perspective, and the retelling of experiences. Those experiences are inherently different, and, naturally, the music is as well. While not all music fits all tastes, it is all a valuable part of the human experience and its artistic documentation and legacyf. The deliberate omission of works by women composers and BIPOC composers continues to reinforce the deeply unfortunate and also seemingly immovable foundations in white supremacy and patriarchy that continue to dominate every aspect of classical music education and performance.

We will continue to call for change, and to hold these 21 high-budget ensembles – the ones with the most influence, funding, and opportunities – accountable for their oles of leading the change that is needed, that is being called for, and that is the only viable way forward for classical music.