That the professional music world, and professional orchestras in particular, aren’t known for welcoming women musicians with open arms isn’t news. It is a truth and a challenge that women have always faced and, as was recently reported by the BBC, is an ongoing concern.

But of the challenges that women musicians have always been up against, from being thought not physically capable to play among men to the problem of being “too distracting” (I’m afraid I’m not joking), one of the greatest concerns is still largely unaddressed even today: the lack of compositions by women composers being heard on symphony stages.

There has been conversation as of late about the limited range of symphonic repertoire in general. After hundreds of years of compositional history, and thousands of pieces to choose from, the greatest orchestras in the world (with the most resources at their disposal and most devout audiences), continue to turn to the same “masterworks” season after season.

Martin Anderson, in his first blog post on behalf of Toccata Classics, raises this point noting that “95% of (classical music’s) assets (are) unheard.” With the countless works that are hidden in archives or simply ignored on library shelves unperformed and unrecorded, how can we possibly stand to sit through another concert season of Bach, Beethoven, and the boys? Scott Cattrell of the Dallas News points out specifically the lack of works by American composers in today’s repertoire and goes to such lengths of suggesting pieces that should be included on concert programs, including—and here we get to the heart of it—Amy Beach’s Symphony in E Minor.

We should be concerned not only with the number of women in top symphony jobs, or conducting major ensembles, but also with the representation of women’s works on concert programs. The statistics on all fronts are shocking – but unlike the (halting and agonizing) progress that women are making as professional musicians, the role of woman as composer, and in particular the recognition of works by historic composers, is making little to no progress at all.

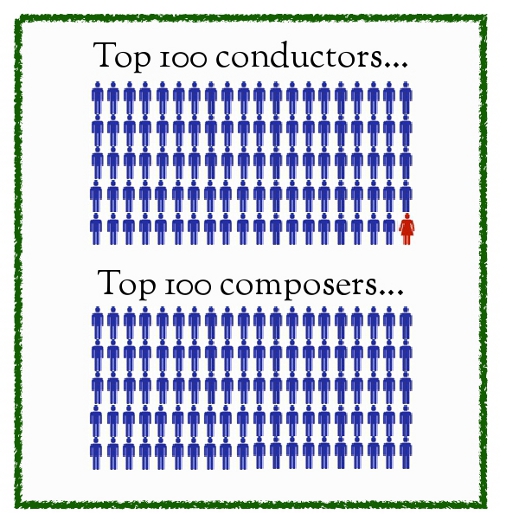

In the 2013 year end review of classical music performance from around the world, as tracked by the website Bachtrack, the figures for performances of works by women were, as the article states, “rather discouraging.” Not a single woman was represented among the top 100 composers heard throughout the year. Clara Schumann rose the highest—at 182. (And of conductors, only one woman—Marian Alsop, the acclaimed music director of the Baltimore Symphony and principal conductor of the São Paulo State Symphony.)

Tom Service, of The Guardian, sums it up fairly succinctly:

Together, those statistics are a revealing indictment of the gender imbalance of the industry, and despite any protestations to the contrary, there’s still a ludicrously long way to go.

Looking ahead to the rest of the 2013-2014 concert season, it is clear that the classical music community is indeed a very long way off from significant change. In a quick review of the 2013-2014 season schedules of nine of the top orchestras in the United States (deemed “busiest” by BachTrack for 2013), five are performing a single work by women composers this season—and while there is good news in that all five works are contemporary (and most were commissioned by the performing ensemble), it shows no progress in the representation of works by historic women.

Boston: no works by women

Chicago: Anna Clyne – <<rewind<<

Cincinnati: Jennifer Higdon – On a Wire

Cleveland: Gabriela Lena Frank, commission – Piccolo Concerto

Los Angeles: Missy Mazzoli, commission – Sinfonia and Bolts of Loving Thunder (Piano Solo)

New York: No works by women

Philadelphia: No works by women

San Diego: No works by women

San Francisco: New commission from Zosha Di Castri

Clearly, I am not the only one who is interested in hearing something new and recognizing the value in a work not yet deemed a “masterpiece”—or who that feels that the work of women is, as a whole, tragically unrepresented in concert programs. In the current market of continually falling ticket revenue, perhaps music directors and conductors will pay attention to these conversations that are taking place. This will encourage them to break away from what has become the fixed repertoire to include more interesting and innovative programming, leading to more diverse and larger audiences (and revenues). I’ll look forward to the 2014-2015 season announcements, hopeful for more progress. We have a ludicrously long way to go.