By Sarah Baer

Our 2023-2024 repertoire report for the top 21 orchestras in the US (as determined by operating budget) is out — with not-great news about the current state of programming as it relates to works by women and non-binary composers. In this post I’m returning to the same data set and looking at the representation and inclusion of BIPOC composers, in particular in comparison to last year. Note: this data refers to Black and Indigenous People of Color, and the individuals included were self-identified as such. However, it may be unintentionally omitting BIPOC individuals that don’t specifically identify as such.

Orchestras across the United States began programming more works by BIPOC composers directly after the murder of George Floyd, amidst the protests and upheaval that followed. Their true motivations are always unspoken – whether they actually want to stand with the Black Lives Matter movement in calling for an end to police violence and equity for BIPOC people, or if they were just riding the tide of what was popular, got good publicity, and allowed for marketing opportunities to place their brand in a timely light.

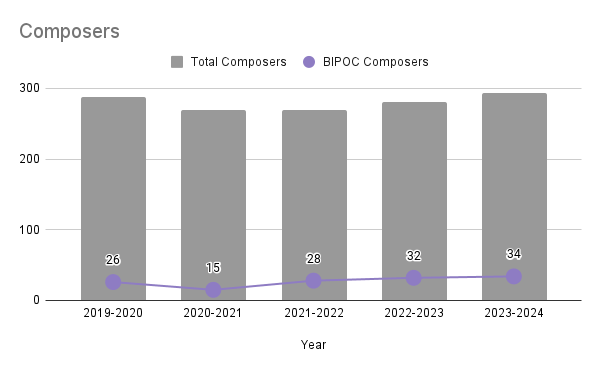

To get a sense of overall trajectory, I looked at the data from the past five seasons of programming, beginning with the 2019-2020 season. Though the pandemic shutdown disrupted planned programming as of March 2020, it’s important to remember that these concert schedules were released in the spring of 2019. When looking over the five-year period we can see that the number of BIPOC composers being programmed fell dramatically in the 2020-2021 season (where concerts were largely only taking place virtually and with chamber works to meet Covid-19 restrictions), but has been increasing since. The composers range from historic (Le Chevalier De Saint-Georges, William Grant Still, Florence Price, Julia Perry, and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor) to new commissions (Jessie Montgomery, Valerie Coleman, Hannah Kendall, Tania León, and James Lee III). Familiar names return year after year, with some variations and new inclusions.

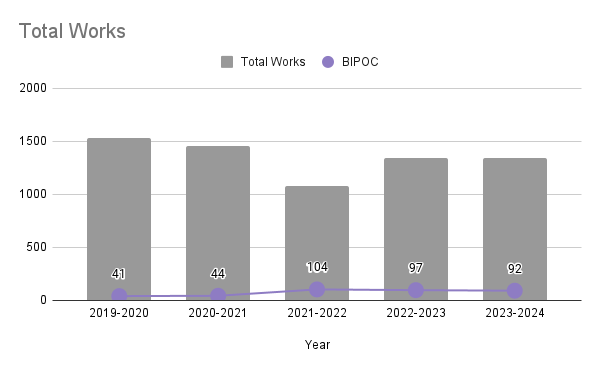

However, the far more interesting data set is the number of performances of music by BIPOC composers heard over the course of the five seasons. There was a clear reaction to the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the overwhelming call for more equity throughout society, including the arts. The number of works by BIPOC composers being performed more than doubled from 44 in 2020-2021 to over 100 in the 2021-2022 season. However, since that peak there has been a small but steady decline in the number of works being programmed.

We see a similar trajectory from the same ensembles when looking at the number of works by women composers being performed – after the performative allyship with issues surrounding representation and inclusion, the entrenched culture of white supremacy and patriarchy make sure the old, “comfortable” programming returns.

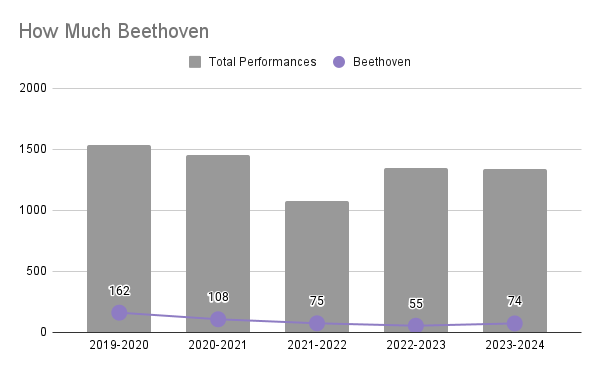

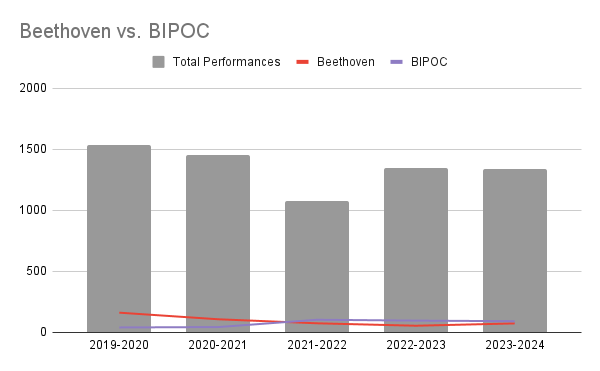

I also couldn’t resist comparing these numbers to the performances of works by Beethoven:

While we saw a dramatic decline in the performances of dear old Ludwig during the pandemic, those numbers are again on the climb.

It’s not hard to predict what the 2024-2025 season will hold if these patterns continue. The masks of feigned alliance with social justice movements are slipping. If they are at all sincere in their commitment to dismantling the systems of white supremacy and patriarchy, these institutions need to step up to a stronger commitment.