We apologise for taking so long to get back to Part II of our post about composer and violinist Maddalena Laura Lombardini Sirmen (1745-1818). Part I, about her life, is found here. Our guest author is the London-based musician Martin Ash, whose website is www.martinashmusic.com.

When Maddalena Laura Lombardini Sirmen embarked on her career, the most standard chamber music format was the trio for two violins and bass (in theory any instrument, though cello was increasingly required in title pages and in compositional demands). Her op. 1, like many other composers’, was therefore a set of trios, six of them in this case. (At this date, opus numbers were applied by publishers not composers and so indicate order of publication rather than composition. As publishers and composers did not always communicate closely, they also do not necessarily form an orderly sequence.)

Like many other instrumental compositions of the time, they are referred to as ‘sonatas’ in the early editions, but they should not be thought to be baroque trio sonatas, a style which was long out of fashion by 1770. Each has two movements, a common structure in early Classical chamber music. The first movements are in sonata form, generally with a recognisable development section (a lot of first movements, particularly chamber music ones, at this date were still in a ‘rounded binary’ form in which there was no thematic development), though in the fourth trio the tempo is Andante and in the last, Lento, making them effectively slow movements. The finales use the common choices for the time of minuet or rondo; but it should be noted that rondo finales were at this early date a quite modern, even innovative, and more ambitious structure often reserved for orchestral compositions. Also, while rondos with a rhythmically contrasting final episode became fairly common, in half of the trios Lombardini Sirmen wittily plays with the conventions by writing rondos which alternate two tempi and time signatures (one for the subject, the other for all the episodes), one of which is a minuet and the other a brisk two beats to a bar as commonly used for rondo finales.

The second violin part largely divides its time between voice-leading of the first violin’s melody and straightforward accompanying patterns of the kinds familiar to any listener to Classical music. The cello part is frequently confined to repeated or held bass notes, alternating octaves and broken chords for most of a movement on end, but there are several occasions where it breaks out into much more surprising demands, which back up the title pages’ specification of violoncello obbligato. Tenor clef and treble clef 8vb are used, and these upper register passages involve themselves in the violins’ melodic material.

All in all, it is clear that Lombardini Sirmen was in mature command of the art of composition by the time of these first publications, and that she was by no means bound by convention, though there is nothing here so exceptional as to cause controversy that might damage sheet music sales. The trios are perhaps ignored today because the format has not returned to the mainstream of chamber music performance, or perhaps because of the continued cultural erasure of women composers.

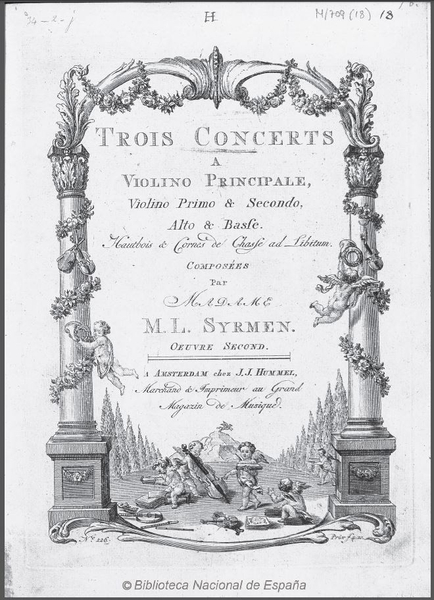

Lombardini Sirmen’s opus 2 consists of three violin concerti. Opus 3 consists of six: the same three, plus another three! All six are now usually referred to by their op. 3 numbers only. Given they were published in Paris during the concert tour with Ludovico, it seems likely that at least some of the concerti were composed in advance of the tour for use on it. However, the lengthy stay in Paris, including at least the later stages of Maddalena’s pregnancy and the nursing of her newborn daughter, may have provided some time for composition too, even if she did not compose ‘on the road’ (as many touring performers did). Interestingly, one Tommaso Giordani adapted the set as harpsichord concerti, seemingly in time for the sets to be published simultaneously; someone must have felt the pieces were good enough to justify investing time in the alternative versions.

The orchestra is the standard early Classical concerto: one of pairs of oboes and horns (all in theory dispensable), first and second violins, violas and ‘bass’ (which would have been used by cello, double bass and keyboard continuo). All are in the usual three movements, sonata form, slow, rondo, with space for improvising a cadenza at the end of each movement and a ‘lead-in’ from each episode of the rondo back into the theme. However, the rondos are less formulaic than many of the time, particularly as the rondo subject (often printed only once at the time!) is usually given substantially different orchestration on at least some of its occurrences, or even interrupted to head off in a different direction before it has concluded. Once again, Lombardini Sirmen was not necessarily going to settle for the easiest and most conventional option if she had more interesting ideas.

The listener’s ear is immediately caught by the near-constant rhythmic variety of Lombardini Sirmen’s writing, in any of her compositions (she has a particular love of swapping between triplet and duplet rhythms), and by a knack for witty chromaticisms. Another highly striking feature, certainly compared to more familiar Classical concerti, is that the bass (and therefore the continuo’s thickening as well) and viola are almost always tacet during the soloist’s passages, making a radical change in texture and tessitura as only violins are playing. The soloist is required to deliver clean execution of very fiddly ornamented fast passages in many places in the outer movements, and to ascend into what are still today considered quite high registers. In the first three concerti, double, triple and quadruple stops are generally ones which lie easily under the fingers and the same ones are often required of the orchestral violinists. We might guess at Lombardini Sirmen gathering ideas from other violinists between Venice and Paris, since there is much more expansive use of double stops, particularly voice-leading in thirds and sixths, in the solo parts of the fourth, fifth and sixth concerti which were first published as part of the op. 3 set.

The fourth concerto has the two-rhythm rondo finale we encountered in the op. 1 trios – evidently Lombardini Sirmen was fond of the device around this time. In this case the two time signatures do not map neatly onto the rondo structure however, making this movement unique. In the fifth, the variation of the rondo subject extends to the point that we might suggest it is being ‘developed’; the division of solo and tutti passages in the finales in particular develops away from the large-scale blocks typical in early Classical concerti towards the flexible dialogue that would characterise the later part of the period and the transition to the Romantic concerto.

Lombardini Sirmen was an ‘early adopter’ of the string quartet, publishing her set of six in 1769 when the trio was still the dominant chamber music format and only a few years after the Haydn set that is generally considered to initiate the genre as we know it. Like the trios, the quartets are in two movements each. However, they are notable for the interest of the inner parts – the importance of quartets being fun for all four players, as essentially participative amateur music rather than performance material, appears to have been realised by the composer. These have been the most popular of Lombardini Sirmen’s works with recording artists, and it is not hard to see why; they are assured, well-balanced between the four instruments, and show the same boundary-pushing attitude to, in particular, tempi within movements notable in the trios and concerti, with perhaps a greater deployment of dramatic contrast. The finale of the second quartet even makes prominent and repeated use of canonic entries between the parts, though there is no pretence of a contrapuntal construction for most of the movement. The finale of the last quartet is another of Lombardini Sirmen’s trademark duple-minuet combination movements, and like some of the concerto finales the framing (non-minuet) material uses unexpected paused rests to rather Haydnesque comic effect. (an excerpt can be heard in this recording).

Like most Classical composers, Lombardini Sirmen wrote overwhelmingly in major keys, though a couple of the concerti have minor-key slow movements. However, the third quartet is in G minor, with an unconventional second movement that alternates fast major-key duple-time and slow minor-key triple-time sections. The first movement of the fifth quartet, meanwhile, has a conventional F major Allegro with slow F minor sections before and after it (so not just the slow introduction that would gradually gather popularity in sonata-form movements throughout the Classical period); and the movement as a whole unusually ends with an imperfect cadence, so that the second movement is necessary to ‘resolve’ it.

String duos were a fairly common early Classical form, with very varying degrees of equality between the parts. Lombardini Sirmen published a set of six as op. 5 in 1775. Structurally they show most of the same features as her earlier chamber music: two movements, sometimes with more than one tempo or metre within the same movement and in one case with a slow movement first. Neither part is exactly easy (both are required to execute double stops, particularly drone notes with a moving part, which is hardly surprising with such limited forces), though only the first part equals the high-register excursions of the concerto solo parts. It would be fair to say that some of the duos are violin sonatas with the accompaniment of a second violin, even including pauses that are almost certainly for the first violin to improvise a cadenza. However, in the second, fifth and sixth duos Lombardini Sirmen engages in more role-swapping, with melodic material in either part and accompanying figures in the other, as well as the passages of voice-leading throughout the duos.

Further resources

A biography, collates known information and documentation (scant and patchy, sadly) about Lombardini Sirmen’s life and music: Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen, Eighteenth-Century Composer, Violinist and Businesswoman, by Elsie Arnold and Jane Baldauf-Berdes. Second only in importance to that for in-depth study is Francesco Passadore’s thematic catalog of the compositions of both Sirmens.

Recordings are still few, but many more and (thanks to the internet) easier to access than they were 20 years ago. There have been two recordings of the complete string quartets, by the Accademia della Magnifica Comunità on the Tactus label and by the Allegri Quartet on Cala. The Spotify artist listing for ‘Maddalena Laura Lombardini Sirmen’ brings up these two albums, and some works on multi-composer albums as follows:

- The third concerto, on Les trésors cachés d’Italie by Stefano Montanari and the Arion Baroque Orchestra

- The sixth violin duet, on Tartini e la scuola delle nazioni, album as a whole credited to Orchestra Barocca Andrea Palladio, again on Tactus

- The second and third quartets, on the Erato Quartet’s 2000 CPO album of Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, Emilie Meyer and M. Laura Lombardini Sirmen

All of these are also available to download from Presto.

Available from Amazon as a physical album (but seemingly not elsewhere) is Baroquen Treasures, by conductor JoAnn Falletta and the Bay Area Women’s Philharmonic (which rebranded as The Women’s Philharmonic): an album of women composers, including Lombardini Sirmen’s fifth concerto with Terrie Baune as soloist.

There is a 2007 recording of the complete set of concerti, by violinist Piroska Vitárius, conductor Pál Németh and the Savaria Baroque Orchestra, on period instruments and with harpsichord continuo. The full set has been uploaded to YouTube by at least three different users (!); the first concerto in one upload is HERE and all are easy enough to find through the search function. The double CD appears to be out of print, but some second-hand copies can be found on Amazon and doubtless elsewhere.

Also on Youtube is the exciting 2011 live performance by Ensemble Mont Rose de la Vallée d’Aoste with le Soliste de Le Cameriste Ambrosiane (the soloist is not named ).

Jane Berdes, a consistent champion of Lombardini Sirmen, edited three of the violin concerti (Concerto I in B-flat Major, Concerto III in A Major, Concerto V in B-flat Major); the scores and solo parts are available to buy and orchestral parts to rent for performance from A-R Editions. Hildegard Publishing, meanwhile, has editions of all the chamber music (duos, trios and quartets) for sale, and German company Furore Verlag have a different edition of the complete quartets, and one of the fourth concerto. Yet a third edition of the quartets is available from SJ Music. All these quartet and Trio editions include scores as well as parts. Theodore Front have taken over supplying the Broude Brothers performing facsimile editions of the duos and trios (Search their website here).

IMSLP has contemporary sets of parts (generally clearly-written and well scanned, so more legible than many scans of 18th-century printings) to the trios, concerti (including the Giordani harpsichord versions) and violin duets, as well as a modern typeset score and parts (interpreting the cello part as continuo, somewhat peculiarly) to the trio op. 1 no. 2, as free PDF downloads.

Barbara Harbach has transcribed the first concerto entire as a solo organ piece, published by Vivace Press (described here, and available from sheetmusicplus) and recorded on her album Summershimmer: Women Composers for Organ.

I for one am excited to learn about Lombardini Sirmen and her music and I hope — once we are back to performing — that more ensembles will take up her music, and in the mean time the chamber works can be explored with social distancing in practice!