We originally published this post on Feb 26, 2021 and are now reposting, since it is so important to our work! Guest author Mary Purpura completed an MA Thesis about The Women’s Philharmonic in 2016. Her research provided an important history of our founding organization, and we encouraged her to draw from her thesis and blog for us! So here it is (the first of several parts), just in time for celebrating the 40th anniversary of The Women’s Phil.

By Mary Purpura, MA, HTR

During my graduate studies in music, I actively sought out information on women composers and conductors. I had heard of so few! I always tried to write my seminar papers on women composers, which allowed me to delve into these women and their works. I wrote about Pauline Viardot, Sofia Gubaidulina, Clara Schumann, and Ruth Crawford Seeger, among many others.

When I started writing about Fanny Mendelssohn (Hensel), I learned about her full-length symphonic work, her Ouverture of 1830. I also learned that it had been premiered publicly in 1992 by The Women’s Philharmonic of San Francisco. Amazing! I grabbed ahold of the end of that golden thread and started pulling. I learned about a nonprofit women’s orchestra—founded by women, staffed by women musicians, showcasing women’s compositions and women conductors—that had survived for nearly a quarter century. It’s hard, isn’t it, to imagine a project like that taking root and thriving in today’s environment.

As I started talking to people about The Women’s Philharmonic (TWP), I began to understand that the organization had deep taproots in my local Bay Area music community. Mariko Abe, the Music Department administrative support coordinator at California State University, East Bay, where I was a student, had played bass clarinet in TWP. One of the administrators had performed for years with TWP’s related community orchestra in the East Bay (the Community Women’s Orchestra, that continues to this day). My daughter’s piano teacher had performed with TWP.

Here’s the thing: Each of these women remembered TWP so fondly. When I mentioned it to Mariko, she closed her eyes, threw back her head, and said, “Oh yes! It was wonderful to play with them. That was a magical time.” This organization had made women feel valued as artists, yes, but its commitment to discovering and celebrating forgotten works by women composers–like Fanny Mendelssohn’s Ouverture–was enlivening and hopeful and positive and strengthening in very specific and nourishing ways.

When I looked for a published history of TWP and didn’t find one, I decided to write a history of the organization for my thesis. As part of my research, I spoke with two of the three founders of the Philharmonic, who generously shared certain vivid anecdotes that offered an incredible picture of what the group accomplished.

One such story was about the Orchestra’s May 1992 performance of Fanny Mendelssohn’s Ouverture. Fanny Mendelssohn wrote over 500 pieces, but only one symphonic work: her Ouverture of 1830. The piece had been performed twice with miscellaneous musicians during her family’s Sunday salons, but had never been performed publicly. (The Women’s Philharmonic Programs, Stanford University Special Collections.) The Women’s Philharmonic members learned (through research) that copies of the score were held at the Mendelssohn Archive in Berlin. The organization did not have the resources to fund a trip to Germany, but when TWP Board Member Judith Rosen traveled there, she visited the archive and arranged for the release of a copy of the score, and for permission to perform and record the work. The program notes from the concert stated:

As is the case with many historical works rescued from obscurity by The Women’s Philharmonic, this manuscript, written in Fanny Mendelssohn’s own hand with numerous corrections, smudges, and other ambiguous markings, required extensive reconstructive work prior to its first Women’s Philharmonic rehearsal. (The Women’s Philharmonic Programs, Stanford University Special Collections)

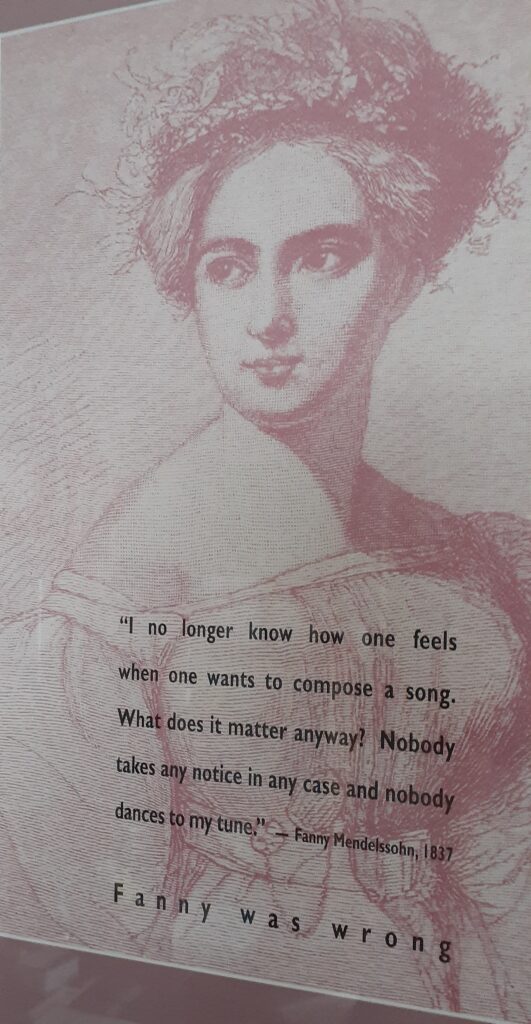

The program also included a quote from Fanny Mendelssohn: “I have composed absolutely nothing this winter (1837). I no longer know what one feels when one wants to compose a song. What does it matter anyway? Nobody takes any notice in any case and nobody dances to my tune.” (The Women’s Philharmonic Programs, Stanford University Special Collections) Later, TWP staff had a poster made with this Mendelssohn quote on it and a final added line: “Fanny was wrong.”

At that May 1992 performance of Mendelssohn’s Ouverture, both Executive Director Miriam Abrams and Music Director JoAnn Falletta gave pre-concert talks about the historic nature of the show that was to follow. Between the talks and the program notes, the audience knew they were participating in something unique and special. And here’s the image that has really stayed with me, ever since I heard the events of that day described: At the end of the concert, JoAnn Falletta fanned out the pages of the score and, holding it out in front of her as if it were holy scripture, she walked through the audience. “People in the audience were crying and cheering,” said WP co-founder Miriam Abrams. “They knew they were there for a historic moment.”

The persistent and painstaking work that went into making that performance of the Ouverture will be understood and appreciated by anyone working in the field of women’s music history. We can imagine that much has been lost—manuscripts written by women that were not valued, and thus have not survived, as well as compositions by women with great talent and potential that were never realized because of lack of support or competing demands on their time because they were women.

I began to fully grasp the dimensions of this issue: how much has been lost—and thus how incredibly precious is what survives—while researching my graduate thesis. In Part II, I’ll share several anecdotes and experiences really drove home how we hold on to what remains of our precious women’s musical history by a thin and fraying thread.

Listen to The Women’s Philharmonic performing Fanny Mendelssohn’s Ouverture, on their second commercial recording (1992) — amzingly, still the ONLY commercial recording of that work! Directed by JoAnn Falletta, this classic CD first brought Fanny Mendelssohn’s Overture of 1830 to light. Also, the first recording of Germaine Tailleferre’s Harp Concertino, and works by Lili Boulanger and Clara Schumann. Koch International Classics, 1992; reissued 2008 with support from Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy.