Distinguished Guest Blogger Timothy Diovanni joins us again with a sequel to his previous article about Germaine Tailleferre, Malicious Men: The Harmful Effects of Tailleferre’s Father and Husbands on her Life and Career.

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, 1913

Imagine yourself in Paris in late May of 1923. You stand in front of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, an ornate hall constructed ten years prior, in anticipation. Today’s performance includes the premiere of Le Marchand d’oiseaux, with music by Germaine Tailleferre, story, costume, and production by Hélène Perdriat, and choreography from Jean Börlin. The Eiffel Tower looms darkly to your left. You spot Darius Milhaud, here to see his close colleague’s opening night. Your friend leans over to say that they recently heard Ricardo Viñes solo in Tailleferre’s Ballade for Piano and Orchestra. They enthuse about Tailleferre’s musical style. You enter the theater, show your ticket to the steward, and take your seat.

That night, back in your six-floor walk-up, you write home to describe how much you enjoyed the ballet. You want to see it again, and do so a week later. You’re elated.

You live in Paris for the rest of your life. Yet, you never hear even a mention of Le Marchand d’Oiseaux again.

What happened to it?

Contemporary critics are notably to blame for the disappearance of Tailleferre’s Le Marchand d’Oiseaux. In response to the premiere, Raoul Brunel wrote in the Echo de Paris, “The hall applauded a long time and called back to the stage the two young authoresses, who were probably amused by their production of this fun spectacle, as much as we were to watch it.” [Emphasis added by the author throughout.] Brunel’s assessment makes it seem as if Tailleferre and Perdriat constructed their ballet casually, without care. His demeaning comment steered intellectual discussion away from the work.

Perdriat’s sketch of the bird merchant (Accessed from Heel’s dissertation)

André Levinson of Comœdia chimed on a similar note, “Le Marchand d’oiseaux has indeed the futile but coaxing charm of feminine things.” These trifles did not deserve respect, the critic suggests, so they were laughed away with the stroke of a pen. Most acidic, Charles Tenroc of Le courrier musical de France even suggested Perdriat and Tailleferre had “nothing better to do,” hence they “amused themselves by dressing up their dolls.” (See Laura Hamer’s Germaine Tailleferre and Hélène Perdriat’s Le Marchand d’oiseaux (1923): French feminist ballet? and Kiri Heel’s dissertation Germaine Tailleferre beyond Les Six: Gynocentrism and Le Marchand d’Oiseaux and the Six Chansons Françaises for more on these critics’ effects. I am indebted to both authors for these above translations.)

The responses to Le Marchand d’oiseaux responses demonstrate the pervasive style of the criticism used to reflect on Tailleferre. Critics discussed Tailleferre’s works using gender-coded traits, such as “sensitive,” “seductive,” and “pretty,” terms that relegated Tailleferre to a compositional niche based on an aesthetic of pleasure; they evaluated her music predominantly in reference to prominent male composers; and they described her appearance in order to thrust her into a satisfaction role. In taking these approaches, critics shaped the desire of and interest by musicians (from the time of their writings up to the present-day) to perform, record, or commission works by Tailleferre.

American critics of the 1920s tended to emphasize Tailleferre’s visual appearance. Deems Taylor, an American composer and music critic of The World, had the audacity to write that although he found Tailleferre’s music subpar, at least she was “decidedly the best looking” of Les Six. A year later, an unnamed Boston Daily Globe critic, after seeing Tailleferre take her bows with Serge Koussevitzky for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s performance of Jeux de plein air, evaluated Tailleferre’s beauty. “She has barely turned her thirties and they are kind; she is fresh and charming, modest and gay. Her dressmaker does a capital job, and she, like every onlooker, appreciates it… Music or no music, not often on a Friday afternoon does the stage of Symphony Hall proffer such a figure.” Olin Downes of the New York Times called Tailleferre “precociously gifted and pleasant to look upon” (He proceeded to question Tailleferre’s originality). Paul Rosenfeld, a New York music critic, suggested Tailleferre’s inclusion in Les Six was merely a byproduct of “a fine enthusiasm for the sex on the part of the five male members.” The New York Times announced Tailleferre’s arrival to New York City in February 1925 with a description of her as a 26-year old “attractive blond with slim graceful figure and blue eyes.” Not only did the New York Times shift the focus from her music to her body, but they also littered the clip with inaccuracies and inconsistencies.

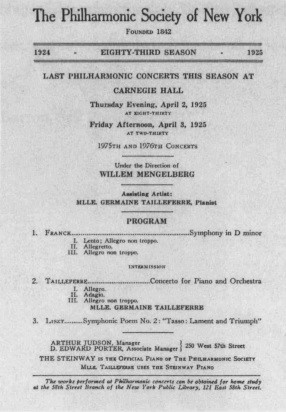

Program advertising Tailleferre’s performance of her Piano Concerto in NY, April 1925 (Accessed from Hamer’s Women Musicians in France during the Interwar Years, 1919-1939)

These American critics focused on Tailleferre’s body in order justify the existence of a woman composer in the world of classical music composition. By focusing their attention on Tailleferre’s appearance, critics disregarded both the quality and the and reception of her work. This is obviously a gender-specific problem.

In other cases, American newspapers chose to compare Tailleferre’s music to more famous (male) composers. In a 1925 clip in The Boston Daily Globe, an anonymous critic juxtaposed Tailleferre’s Piano Concerto (1924) against Stravinsky’s, “But his [Stravinsky’s] concerto has significant and beautiful melodic ideas, or themes in it and hers has not.” The critic did not describe what they heard in Tailleferre’s concerto, rather they compared in order to subordinate through unoriginality. This degradation not only ignored Tailleferre’s actual achievement, but also pushed the concerto out of the public’s recognition. Since (according to the critic) Tailleferre’s concerto was simply a poor imitation, why not just program the authentic Stravinsky to get the “better” version of the work?

Critics justified Tailleferre’s presence in the male-dominated field of composition by conflating the sound of her music with her gender. Her work was described as “pleasant,” “lively,” and “sentimental,” among other similarly feminine terms. Since the feminine has been historically devalued, the critics thus marginalized Tailleferre’s oeuvre.

When asked about the feminine aspect of her reception, Tailleferre responded:

The essential thing is that it be music. I don’t see any reason why I shouldn’t write what I feel. If it gives the impression of being feminine, that’s fine. I was never tormented by explanations. I tried to do the best I could, but I never asked myself if it was feminine or not. If it is music, it is music. I find that I place myself more among the little masters of the 17th and 18th centuries. I have always been attracted to simple things like that. (Quote from One of ‘Les Six’ Still at Work, Laura Mitgang)

While Tailleferre attempted to compose unhindered by criticism, femininity’s traditional connection with triviality decreased the interest for her music. Moreover, the preceding quote exhibits Tailleferre’s routine degradation of her music (“I place myself more among the little masters.”). Her self-diminution—a performance of femininity—hurt her reception.

As time passed and the memory of Les Six grew more distant, music historians determined that they needed to address the group’s legacy. The authors exhibited several main characteristics, all of which negatively shaped Tailleferre’s reception. The writers consistently:

- Dismissed Tailleferre’s work as inconsequential.

- Directly compared her to Louis Durey, one of Les Six.

- Asserted the concept of pleasantness in her music.

- Employed perceived-importance wording, i.e., wording that expresses ranking by placing the more important elements first.

- Described her work only in comparison to more famous male musicians.

- Labeled her as the “most in tune with” neoclassical ideals, thereby creating a false aesthetical narrative.

- Omitted any discussion of her oeuvre post-Les Six.

- Expanded upon Honegger’s, Milhaud’s and Poulenc’s career only.

The earliest textbook example was penned directly following the Les Six period. Cecil Gray in Survey of Contemporary Music (1927) created an awful metaphor: “Of Mlle Germaine Tailleferre one can only repeat Dr Johnson’s dictum concerning a woman preacher, transposed into terms of music. ‘Sir, a woman’s composing is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well, but you are surprised to find it done at all.’” The quote stung with patronization. Gray condescendingly called Tailleferre “Mademoiselle,” then promptly dismissed her entire creative oeuvre.

Other textbooks written while Tailleferre was alive were summarily dismissive. Martin Cooper in French Music from the Death of Berlioz to the Death of Faure (1951) stated, “The music of Germaine Tailleferre embodies many of the more feminine characteristics of the new school…. It was indeed a happy time for the little talents.” Joseph Machlis in Introduction to Contemporary Music (1961) commented that “Durey and Tailleferre, after a brief taste of fame, passed into obscurity.” Peter Yates in his prematurely-entitled Twentieth Century Music (1967), asserted, “Two of ‘the six,’ Durey and Tailleferre, came to nothing.” Mosco Carner claimed in The New Oxford History of Music: The Modern Age 1890-1960 (1974), “Durey and Tailleferre are the least significant members of the group…Tailleferre wrote for the most part small-scale, unpretentious, and rather short-winded works possessing, however, a typically Parisian chic and elegance.” In 1979, Machlis slightly revised his negative assessment, “Of the six, two–Louis Durey and Germaine Tailleferre–soon dropped from sight.” Crucially, Tailleferre was still composing when these textbooks were published. In effect, the historians closed the book on her career before it ended.

Authors have continually written Les Six names in a priority-based order, with the composers that the writers deemed most important at the front of the list. Tailleferre was at the end of these rankings. From their hierarchies, historians chose Honegger, Milhaud, and Poulenc as the most important and devoted paragraphs to their music. Tailleferre was disregarded. Even when Tailleferre managed to appear in a textbook independent of her Les Six connection, the writer’s estimation of her emerged through word choice and sentence structure. In A Chronicle of 20th Century Music (1984), Richard Burbank described Tailleferre’s premiere of her Piano Concerto:

Serge Koussevitzky premieres the Piano Concerto, by Germaine Tailleferre, the female member of Les Six. The performance takes place in Paris, with the composer as soloist.

On the very same page, Gershwin’s premiere of his Piano Concerto is described thus:

George Gershwin is soloist at the world premiere of his Concerto in F for Piano and Orchestra, as Walter Damrosch conducts the NY Symphony.

Burbank crafted these reflections on one page. However, the excerpts asserted different historicization priorities. For Tailleferre’s Piano Concerto, the hierarchy is 1. Conductor 2. Composer and soloist; while for Gershwin’s it’s 1. Composer and soloist 2. Conductor. Tailleferre was introduced by the more famous male, Koussevitzky: She needed his authority for inclusion. Conversely, Gershwin was considered a prodigious enough (male) composer to hold priority, with the conductor left in a tertiary position.

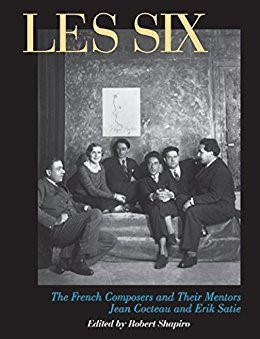

Recent textbooks have treated Tailleferre more fairly. But, writers still employ techniques that discourage inquiries about Tailleferre. They continue to order Les Six names according to their perception of success and assert pleasantness in Tailleferre’s music. Despite increasing Tailleferre recognition, Robert Shapiro evaluates Tailleferre’s oeuvre using the latter methodology. He ends his chapter on Tailleferre in Les Six: The French Composers and Their Mentors Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie (2011) thus:

“…Tailleferre was successful as a composer of music because she was able to translate her intriguing interior life into a form of expression that is at once deceptively simple but to which are attached threads of human insight too compelling and characteristically too pleasing to ignore or to dismiss.”

In Shapiro’s view, pleasure is yet again the byproduct of a woman composer’s work. Some scholars argue that feminine terms, like pleasure, were used to describe music by French composers en masse. However, Shapiro emphasizes pleasure only in Tailleferre’s music; he does not do so for any other member of Les Six. Furthermore, critics and historians have historically labeled the music of the rest of Les Six as “masculine” because of jazz influences. Tailleferre’s work has evidently been valued with different gendered terms than her compatriots.

Given the work of critics and historians, how can contemporary writers and musicians respond? It is paramount for authors to reevaluate their treatments of Les Six. It is simply historically negligent to list then promptly dismiss Tailleferre without a consideration of the actual significance that she achieved. Authors can highlight Le marchand d’oiseaux, which was performed by the Ballet Suédois more often than any other Les Six work. I like the direction of Taruskin’s survey, which acknowledges prejudices against women composers and describes Tailleferre’s “Quadrille” from Les mariés de la Tour Eiffel (1921) (The Oxford History of Western Music, 2005). I prefer Bonds’s textbook, which analyzes the finale of Tailleferre’s Harp Concertino (1927) (A History of Music in Western Culture, 2010). Bonds’s study stirred my interest in Tailleferre’s music, which demonstrates the impact that textbook writers can have on their audiences.

In the concert hall, Tailleferre’s work can be integrated into a variety of genres, from chamber to ballet to solo piano recitals. Score location remains an obstacle, as orchestrations of Jeux de plein aire and Le marchand d’oiseaux, have gone missing. It is exciting to find a recording of the latter on Youtube, but it provides no information about the sources for the recording (apart from naming the conductor). Is it a reconstruction? How can score and parts be accessed?

While advocates scour for Tailleferre’s music, there is still plenty to play. I, for example, will perform Arabesque pour piano et clarinette (1973) in October as part of a chamber recital. I will preface the recital with a synopsis of Tailleferre’s career, in which I will highlight the social agents that caused her current obscurity.

Despite over 100 years of written neglect, I see new Tailleferre perspectives blossoming. I highly recommend research by Laura Hamer and Kiri Heel, whose assessments have guided my pursuits. Because of the recent re-thinkings, increase in performances, and uptick in recordings, I am hopeful that audiences and musicians will learn and care more about Tailleferre.

With persistence and energized support, you—the imagined Parisian—might even one-day see Le marchand d’oiseaux at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées again.