By Dr. Amy Zigler, an Ethel Smyth scholar and Associate Professor of Music at Salem College. She will be speaking about the recording, the female characters, and issues of agency in Der Wald at the Operatic Feminisms symposium on March 25, 2023, at Columbia University. Event info here.

On January 10-12, 2023, I had the privilege of attending the world premiere recording of Dame Ethel Smyth’s second opera Der Wald. The recording session took place at the BBC Maida Vale Studios in London; it was conducted by John Andrews of the National Symphony Orchestra (UK) and the English National Orchestra and performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Singers. Principal roles were sung by Robert Murray (Heinrich), Natalya Ramaniw (Röschen), Claire Barnett-Jones (Iolanthe), Morgan Pearse (Rudolf), Andrew Shore (A Pedlar), and Mathew Brook (Peter).

Portrait of Ethel Smyth by Aime Dupont, 1903

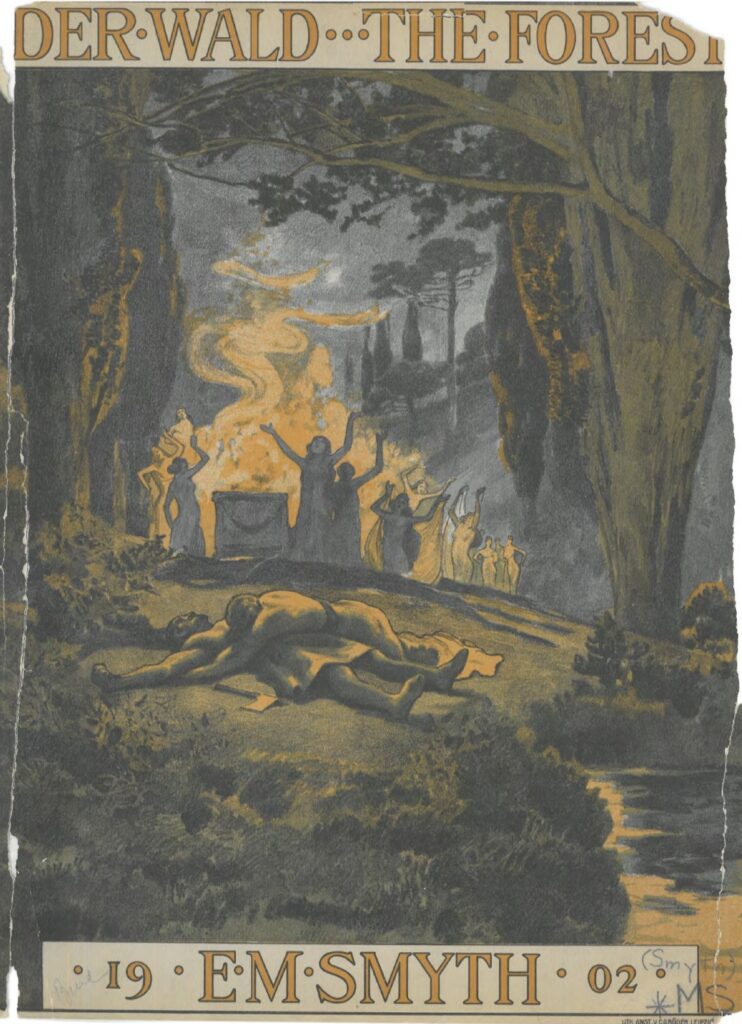

Der Wald, a one-act late Romantic opera, premiered in Berlin and London in 1902, was the first opera by a woman to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1903 and was last seen in 1904 in Strasbourg. 119 years have passed since it was performed by a professional opera company. Articles and dissertations have been written on the work since then, but none of us have heard it and we had no way to judge the validity of audience or critic reaction – until now.

Der Wald is a composition influenced by Brahms and Tchaikovsky but also Massenet and Puccini. Smyth’s orchestration of the work and her treatment of the voices is powerful and poignant. The prologue and epilogue exhibit lush string writing, colorful use of winds, and an ephemeral choir. Within the nine scenes, Smyth has written gorgeous and haunting solos for the viola, bass clarinet, and cello. Like The Wreckers (1906) and The Prison (1930), the harp also figures prominently throughout. Hearing the fully realized version of this work has altered my interpretation of it. John Andrews expertly led the seventy-five members of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble that included the usual slate of woodwinds plus no less than three trumpets, two trombones, bass trombone, tuba, five horns plus an offstage horn. In 1903 this was described as a “clangor of brass, the shrieks of strings, and the plaint of wood winds,” but 120 years later Smyth’s orchestrational choices deftly match the story as it unfolds. While Smyth often treats the orchestra as a collection of soloists in this work in order to balance with the voices, some of the most powerful moments, including the love duet between Röschen and Heinrich, are bolstered by the full orchestra.

Smyth’s writing for the soloists is at times better than in The Wreckers. The melodies are more natural, more tuneful, more memorable even, despite their difficulty. Heinrich’s lied is folklike, befitting his profession as a woodsman, while the baritone Peddler sings mostly in an expected patter style. The writing for the two lead female characters presents a curious case study in vocal type. In the 1902 Schott-Söhne vocal score, Iolanthe, the purported witch, is listed as a “Soprano, (or Mezzo-Sop.);” on this recording, it is superbly sung by mezzo-soprano Claire Barnett-Jones, whose wide vocal range was perfect for the role. Röschen, the “innocent” bride-to-be, is also a soprano role, skillfully navigated by Natalya Ramaniw. In fact, the two roles have the same range, C4 to B6, raising questions too speculative to be addressed here. For now, I will simply say that the music presents both women as powerful and independent, a treatment I did not expect, and a refreshing change in fin-de-siècle opera when power and independence were seen primarily as female vices.

The full recording of Der Wald is slated for release in the Fall of 2023 on the Resonus Classics label.