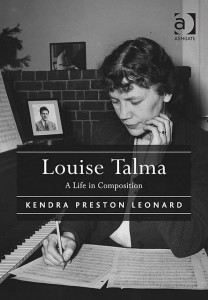

Featured Guest Blogger: Kendra Preston Leonard

We are happy to be launching a new series of guest bloggers. Leonard’s book Louise Talma: A Life in Composition (Ashgate) was published last year and caught our attention, so we are honored to have her as our first “FGB.” A musicologist whose work focuses on women and music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; music and screen history, and music and disability, Kendra Preston Leonard is the Director of the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive. The intro chapter to Leonard’s book on Talma is available as a PDF, or through Amazon with the Kindle App. The essay below is drawn from the book, but also from Leonard’s other research. She will continue her exploration of Talma’s music in future blog posts, as well!

We are happy to be launching a new series of guest bloggers. Leonard’s book Louise Talma: A Life in Composition (Ashgate) was published last year and caught our attention, so we are honored to have her as our first “FGB.” A musicologist whose work focuses on women and music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; music and screen history, and music and disability, Kendra Preston Leonard is the Director of the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive. The intro chapter to Leonard’s book on Talma is available as a PDF, or through Amazon with the Kindle App. The essay below is drawn from the book, but also from Leonard’s other research. She will continue her exploration of Talma’s music in future blog posts, as well!

American composer Louise Talma (c. 1906-1996) is today best known for her vocal and choral works, but she also wrote several works for orchestra and orchestra plus vocalists. These works are infrequently performed today, in part because of a lack of available printed parts and scores. Interest in her music will, I hope, help bring about the greater availability of her music for larger forces.

Following her 1934 conversion to Roman Catholicism, Talma composed a number of religious works or pieces that set religious texts: In 1934 or thereabouts, Talma composed her first religious and orchestral work, The Spirit of the Lord for “bass-barytone,” mixed chorus, and orchestra. She followed this in 1938 with The Hound of Heaven, for tenor and orchestra. The Spirit of the Lord is highly representative of her early, primarily tonal period; The Hound of Heaven, which uses a {0,1,4} set—which at the beginning of the piece is realized as {D D# B}![]() —as a guiding mechanism for melodic and chordal constructions, suggests the directions she would later take towards serialism and atonality.

—as a guiding mechanism for melodic and chordal constructions, suggests the directions she would later take towards serialism and atonality.

1934 was an important year for Talma. Following a period of religious study, she converted in July in a ceremony replete with new baptismal names, gifts, and her first communion. Her mentor and close friend Nadia Boulanger stood as her godmother, welcoming her into the faith with a ring and other tokens. Talma’s conversion remains controversial: her initial desire to convert appears to have come from wanting to become closer to Boulanger, whose belief in her faith was absolute, if sometimes unorthodox, and who encouraged many of her students to convert. Nonetheless, once having embraced the Church, Talma defined herself as a devout Catholic for the rest of her life and composed religious works during her entire career.

Talma’s new religion provided her with a wealth of material through which she could express herself. The Spirit of the Lord sets texts from the book of Joel in the Douay-Rheims Catholic Bible, Acts, and Psalms. The chosen texts reify god’s power and position in the life of the believer, god’s ability for munificence and wrath, and praise for god. It seems to reflect Talma’s broad understanding of her new, chosen deity, and her desire to create musical works that celebrate that deity. The work calls for the bass-baritone soloist, 3 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons (one to play contra-bassoon as needed), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, piano, and strings. Talma’s orchestration list calls the latter a “quintet” of strings, but since she indicates divisi in several areas, I would assume she is simply making sure that the typical complement of violin I-violin II-viola-cello-bass is used without omission. The range for the vocal soloist is: ![]() . The work requires an experienced choir capable of chromatically and rhythmically difficult singing.

. The work requires an experienced choir capable of chromatically and rhythmically difficult singing.

Talma uses a fluid approach to meter in the work, creating melodic lines to fit the natural stresses of each line. While the work is non-developmental, like much of her oeuvre, Talma creates a sense of movement through the use of counterpoint and quick harmonic movement. The extant score, available in fair copy at the Library of Congress, is mostly in short score form, but Talma provides the full instrumentation and cues for instruments throughout the score. It has not been published and there do not appear to be any extant parts. There is no record that The Spirit of the Lord has ever been performed.

In 1938, Talma worked on two religious compositions that called for orchestra and voices. Her Domenica Decima Quinta Post Pentecostas, written for tenor, men’s chorus, and orchestra, went unfinished, despite a large number of sketches. However, she did complete The Hound of Heaven, composed for tenor and orchestra, that year, and in many ways it is a more personal and developmentally important work in Talma’s output. The Hound of Heaven is a setting of the famous poem of the same name by Francis Thompson (1859-1907). Thompson, an Englishman whose work influenced J. R. R. Tolkien and other prominent thinkers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, recounts in the poem a conversion narrative, in which the narrator is chased by the force of the Christian God until at last he submits to belief in and obedience to that god. Talma’s own conversion process had not always been easy for her, and the poem spoke to her experiences as an agnostic making what she found a difficult decision to believe in a religion despite her misgivings in things such as Papal infallibility, the Church’s censorship of scholarship and dissent, and its historical treatment of women and minorities. In any event, the work was at least in part a result of her religious experiences.

The Hound of Heaven is one of Talma’s most important pieces from the 1930s and is the first piece in which she uses a metrical/rhythmic device that permeates her later religious works. Throughout the piece, she uses duple meters and rhythms centered on groupings of twos to signify mortal life, while assigning triple meters and rhythms to text signifying or speaking on behalf of the holy. Although the work is, for the most part, freely atonal, Talma moves from tonal center to tonal center to suggest the places of stability the narrator desires before finding god in stable tonal areas around B-flat and, in the end, D minor.

The orchestra Talma uses is described in the score as “small,” and it is likely that she wrote with the intention of a chamber-sized string section and perhaps two players each for the winds and brass. The scoring is for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, trombone, timpani, harp, piano, strings, and solo tenor. The texture throughout is sparse, a characteristic present in much of Talma’s works: it allows the listener to clearly hear the complex rhythmic, metrical, and pitch class set variations and manipulations Talma creates as part of her compositional process. There is some awkward writing for the strings, which is not unusual for Talma’s works. The vocal range for the tenor soloist is: ![]() . Talma’s own fair copy of the manuscript is available at the Library of Congress in the Louise Talma Collection; it has never been published.

. Talma’s own fair copy of the manuscript is available at the Library of Congress in the Louise Talma Collection; it has never been published.

I have digital copies of both of these works that I would he happy to share with anyone who is interested. Recently, the MacDowell Colony, Talma’s legal heir, has been interested in and very supportive of projects and initiatives regarding the publishing and performance of her music, and I imagine that the officers there would welcome a performance and/or recording project.