Today we are delighted to feature the work of Maria Noriega Rachwal, a music teacher and musicologist living in Toronto, Ontario. She lectures widely on women in music and has written articles on the subject for professional organizations. Her work on the Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra was featured on the CBC Radio documentary, “It Wasn’t Tea Time: Ethel Stark and the Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra.” Her new book, From Kitchen to Carnegie Hall, is being released October 6 by Second Story Press.

The twentieth century witnessed the advancements of North American women in politics, suffrage, labour, and education. Despite these gains, the music profession remained largely male-dominated, especially in the field of orchestral playing. To challenge the exclusion from the musical establishment, women created their own music clubs, associations, and women’s chamber groups and orchestras. These pioneering organizations assisted the professional development of female artists, challenged societal norms, and provided a network of support. By 1930 there were more than 30 all-woman orchestras across the U.S. In Montreal, Quebec, Canada, The Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra would become a part of this trend, but its creation was far more ambitious and daring than anything south of the border.

In 1940, the same year that women in Quebec won the right to vote, two extraordinary women, violinist Ethel Stark and socialite Madge Bowen, met for tea at Montreal’s Ritz-Carleton Hotel, to discuss the situation of female musicians. They envisioned a place where ordinary women of all ethnic, religious and social classes could come together to play music. All of this at a time when women were banned from playing in professional orchestras, when women who played “masculine” instruments were ridiculed, and when Montreal society was heavily stratified based on race, class, and language. What no one had anticipated is that this meeting would be the start of one of the most audacious acts of symphonic construction in history: to build the core of their symphony orchestra in ten days, with no funding, with old donated instruments and with “musicians”, who for the most part, had never set foot on stage.

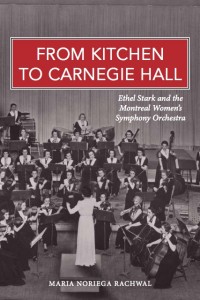

Left to right: Founder Madge Bowen, Guest Violinist Lea Luboshutz, Conductor Ethel Stark, and orchestra violinist Mrs. John Pratt

Ethel Stark, a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, had returned to her native home in Montreal to play on a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) radio broadcast. Hearing of her visit, Madge Bowen, the wife of a wealthy executive, proposed to the violinist a most daring venture—start a women’s string orchestra to train Canadian women for professional careers in music. No one could be better trained for the job; after all, Stark had been the first Canadian woman accepted at the Curtis Institute, the first woman to study conducting with renowned conductor, Fritz Reiner, and the first woman to play the violin under his baton on a coast-to-coast radio broadcast. Madge knew Ethel was a woman of “firsts”, but what Madge had not counted on was that Ethel was also a visionary who was much ahead of her time.

Here is an excerpt from From Kitchen to Carnegie Hall: Ethel Stark and The Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra, of that first meeting:

Ethel looked into Mrs. Bowen’s eyes and gave her an emphatic, “No.” Madge sank back into her seat. Had she heard correctly? She had known it was a risk, but deep in her heart she had really hoped for an opportunity.

Ethel continued. “I’m not interested. Any tink town can get an orchestra of strings together. A city of Montreal’s population and undeveloped talent should be ashamed to think of forming a group of string players, then calling it a woman’s orchestra.… What’s wrong with Canada anyway?”

Madge Bowen was completely taken aback, but before she could utter a word, Ethel’s demeanor softened and with a twinkle in her eye she said, “I’m not interested, unless, of course, it is a full symphony orchestra with strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion.” There was a moment of silence. Ethel continued, “Now that would be quite the feat and well worth my time. Anyone can start a small string orchestra anywhere. But a full symphony orchestra – that’s another matter! Then perhaps I would be interested, because it would be entirely different from anything that is out there. A women’s symphony orchestra conducted and managed by women would be something that would make me stay in Montreal…It must be a large orchestra, with eighty to one hundred players. Mrs. Bowen, I have in mind a symphony orchestra that would measure up to the highest standards. We could call it the Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra.”

Madge Bowen questioned the logistics of such a venture. Where would they find the resources, the instruments, and more importantly the women to play instruments, like the trombone, for at the time there were one or two flute players but no brass or percussion players in Montreal.

“As for the other players, Mrs. Bowen, if they don’t exist, we’ll have to make them!” Ethel exclaimed.

It took Madge a few minutes to absorb the impact of such a grand statement. “But how can we start from scratch?” she asked. “It will take us years to get going! And didn’t you say, Miss Stark, that you wanted to build an orchestra that would measure up to the highest standards?”

“This is what we’ll do,” replied Ethel. “Gather up all the women you can find: pianists, violinists, organists. No previous experience is necessary, except that a woman should know how to read a little bit of music. Ask the women you know, ‘do you have a sister or a friend who plays the piano a little bit, or sings a little bit? Anyone who can read a little bit of music?’ Then, I’ll assign them to what instrument I think they should play.”

“You’re suggesting we open up the orchestra to any woman with a desire to play music, those seeking professional careers as well as those who simply want a chance to play in an orchestra?”

Ethel nodded, and Madge’s excitement grew. She wanted very much to see the orchestra improve the lives of women – all women… “If that’s the case, then I think our mission should be to make the orchestra inclusive of all women: French, English, young, old, no matter what their background,” said Madge. “We women have to band together, especially during this time of war.”

Opening up the orchestra to any woman, of any level of talent and of any social class, was a serious idea to consider, let alone execute. Montreal society was heavily stratified based on class, race, and language. Yet, here was a devout Christian woman of the upper class – who was learning to play the violin at age fifty-four – approaching a young professional musician, a Jewish woman, to be her leader. Madge respected Ethel’s superb artistry, and Ethel respected Madge’s audacity and social vision. Together, they had raised the stakes yet again, and after considering the enormous significance of Madge’s proposal, Ethel nodded. “Cooperation, inclusiveness, and hard work will be the ingredients for our success,” she said.

In ten days, they had gathered up a rag-tag ensemble of housewives, students, teachers, a seamstress, factory workers, a maid, grandmothers—any woman who could “read a little bit of music”—and taught them how to play. The women were Jewish, French and English, black and white, from different religious backgrounds, and their ages ranged from sixteen to sixty. Rumors soon began to spread throughout printed media and amongst critics. Even family members reminded the women of the sad fates of many other such “ladies” organizations: women could not function properly without male authority, what chance could a group of women in Montreal, with no money and no sponsor, have to succeed?

Despite the sneers of the skeptics, the indifference of the press, the lack of money, and all the obstacles they encountered, the women lugged their awkward instruments around, often in sub-zero weather, to rat-infested basements and dimly-lit warehouses to hold rehearsals. Sometimes they rehearsed in their own kitchens, living rooms, and bedrooms because they had no rehearsal hall of their own. Their sorority and love for playing music led them to break gender, racial, and other social barriers. In fact, the MWSO became the first racially integrated complete symphony orchestra devoted to the playing of “classical” or “concert” music in Canada.

In just seven months they performed their first concert to an audience of 5,000 people, and over the years, the orchestra grew in numbers, stability, and range of repertoire. By the end of 1946, the orchestra had given no less than 36 concerts, each received with increasing acclaim. On October 22,

1947, the MWSO became the first Canadian orchestra to play in New York City’s Carnegie Hall, to rave reviews. One of their members became the first Canadian black woman to perform in an orchestra in Carnegie Hall. In the years that followed, offers for tours came in from countries in Europe, South America and Asia.

When one considers its frugal resources, the audacity of its repertoire and its roster of soloists is quite impressive. Featured performers included pianist Percy Grainger, violinist Lea Luboshutz, and cellist Zara Nelsova, among others. Canadian premieres included Arnold Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, op. 4, Ernest Bloch’s Concerto Grosso for String Orchestra, No. 2, and Violet Archer’s “Sea Drift for Chorus and Orchestra”.

After more than two decades of success and numerous concerts, the orchestra dwindled due to financial reasons. Although the orchestra gave its last concert in 1965, its mission to train Canadian women had been fulfilled. Some of the women who trained in the orchestra eventually went on to win positions as orchestral players, music educators, and composers, in Boston, St. Louis, New York City, Toronto, Vancouver, Nova Scotia, and other cities in North America. The work of the Montreal Women’s Symphony Orchestra was one of the strongest stimuli in the Canadian classical music scene, and along with the many other women’s musical clubs and organizations, it became a sort of “women’s movement” in music, that changed the face of classical music forever.