Featured Guest Blogger: Kendra Preston Leonard

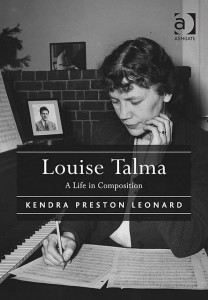

Today we feature the third installment in our Featured Guest Blogger series, again focusing on the work of Kendra Preston Leonard and her new book on Lousie Talma. Leonard is a musicologist whose work focuses on women and music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; music and screen history, and music and disability. Kendra Preston Leonard is the Director of the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive. The intro chapter to Leonard’s book on Talma is available as a PDF, or through Amazon with the Kindle App. The essay below is drawn from the book, but also from Leonard’s other research.

Today we feature the third installment in our Featured Guest Blogger series, again focusing on the work of Kendra Preston Leonard and her new book on Lousie Talma. Leonard is a musicologist whose work focuses on women and music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; music and screen history, and music and disability. Kendra Preston Leonard is the Director of the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive. The intro chapter to Leonard’s book on Talma is available as a PDF, or through Amazon with the Kindle App. The essay below is drawn from the book, but also from Leonard’s other research.

Shortly after her mother Cecile’s death in 1942, Louise Talma found herself in a position in which she needed to assert her

independence as a person and as a composer. During the last years of her mother’s life, Talma had not composed at all, focusing her attentions on teaching and caring for Cecile. When she resumed working again on her own music, she made a number of changes to the ways in which she approached her work: in 1943, instead of going to Fontainebleau or to the American Conservatory’s war-time summer school in New England, she went instead to the MacDowell Colony for the first time. She found that the Colony offered her just the right mix of solitude and companionship—she worked alone all day in the quiet atmosphere of the Phi Beta Cabin, which was outfitted with a grand piano, but took her evening meal with other Colonists in the communal dining room. There she met and became friends with other artists in residence, including Wilder and composers Lukas Foss and Irving Fine. After dinner, she often played pool, a glass of whiskey close by and a cigarette in her mouth.

In both Foss and Fine, Talma found colleagues with whom she could discuss new music and compositional approaches. Foss, a former child prodigy pianist, grew up and trained in Germany and France, and studied composition in the United States. A close friend of Leonard Bernstein and Serge Koussevitsky, he created several ensembles specifically to promote new music. Fine had, like Talma, studied with Nadia Boulanger and was first known for his work in a neoclassical idiom. Foss, Fine, and Talma—along with several other composers—were often considered to form the “Boston school” or “Stravinsky school” of American composition. Although Talma had little if anything to do with the majority of these composers, she shared aspects of compositional language and influences with the group. Fine, describing the music of the group, delineated it as “‘diatonic and tonal or quasi-modal,’ pandiatonic, and concerned with chord spacing and rhythm.” (Phillip Ramey, Irving Fine: An American Composer in His Time (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2005), 49–50). Talma’s major works from the early 1940s can certainly be labeled this way.

Talma began work on her Toccata for Orchestra shortly after completing her first piano sonata in 1943. Like the Piano Sonata No. 1, the Toccata uses a primary dotted-rhythm motif, block forms that include loose variations on key materials, and elements of neoclassicism. That the work is in the form of a toccata and owes a debt to earlier forms and compositional techniques is made clear not just through its title but also the constant motion throughout the piece and the uses of ostinati and pattern completion in it. Indeed, all three of Talma’s major works created in the early 1940s—the Toccata for Orchestra, the Alleluia in the form of Toccata for solo piano, and the Piano Sonata No. 1—use the toccata as a basis for form and compositional practices.

The Toccata for Orchestra was dedicated to Reginald Stewart, the director of the Peabody Conservatory and one of Talma’s friends. It was performed by the NBC symphony orchestra in 1946, and published that year for the Juilliard School by the American Music Center, after winning the Juilliard Publication Prize. While one critic dismissed the work, calling it somewhat repetitive and naïve but nonetheless likely to please audiences, others were more positive. Paul Hume, writing for the Washington Post of a performance in 1963, called it a “stunning, virtuoso affair,” and an anonymous New York Times critic called it “buoyant, youthful music,” albeit having a bit too much “prolixity, repetition, [and] backing and filling.” As Talma’s only work for orchestra at the time of its premiere, the Toccata became popular as a piece that not only indicated an organization’s support for new music, but for female composers as well.

The Toccata, along with her other works during this period, helped Talma secure a place among ranking composers of the day. It is also likely that the success of the Toccata, along with the other pieces she produced in the early 1940s, helped her win her Guggenheim awards in 1946 and 1947, the first time a woman composer had won two Guggenheims back-to-back. Today the work is one of the few of Talma’s pieces that have been recorded. It was recorded in 1961 by Composers Recordings Inc., and appears on a newer—albeit unremastered—release by New World Records on an album recorded by William Strickland and the Imperial Philharmonic of Tokyo that also includes works by Vivian Fine, Julia Perry (like Talma, a Fontainebleau alumna), Mabel Daniels, and Mary Howe.

This recording, despite poor playing by the brass and winds and a somewhat slow tempo, offers a hearing of the Toccata. Talma’s signature counterpoint is on display, particularly in the more lyrical passages. Like much of Talma’s work, it is non-developmental, and the dotted rhythm introduced at the beginning by the trumpets drives the piece forward. The Toccata is more tonal than many of Talma’s works, which likely helped with its reception by general audiences. Nonetheless, it is characteristic in the dominance of rhythm as an organizing concept and representative of Talma’s developing voice.