We are thrilled to share our newest installment in our Featured Guest Blogger series. Dr. Anna Edwards is a conductor and educator in the Seattle area. Two of her ensembles, the Seattle Collaborative Orchestra and the Saratoga Orchestra of Whidbey Island, have been recipients of WPA Performance grants. In addition, she is the music director at Roosevelt High School (Seattle). She received her Doctorate of Musical Arts in conducting at the University of Washington. Her research is focused on the role of gender and the challenges that women conductors continue to face.

We are thrilled to share our newest installment in our Featured Guest Blogger series. Dr. Anna Edwards is a conductor and educator in the Seattle area. Two of her ensembles, the Seattle Collaborative Orchestra and the Saratoga Orchestra of Whidbey Island, have been recipients of WPA Performance grants. In addition, she is the music director at Roosevelt High School (Seattle). She received her Doctorate of Musical Arts in conducting at the University of Washington. Her research is focused on the role of gender and the challenges that women conductors continue to face.

Gender disparity in music: A commitment and a conversation

It has been a joy to see the advances of so many talented women in our musical culture recently: Elim Chan, first female winner of the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition (2014); Susanna Mälkki, recently appointed Principal Guest Conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic; Barbara Hannigan, melding the professions of vocal performer and conductor; composers Caroline Shaw (2013) and Julia Wolfe (2015), recent winners of the Pulitzer prize in music, to name just a few. Communities around the globe should regularly see and hear accolades of the diligence and accomplishments of such phenomenal women. This said, the current climate in the US reminds me that we all must be vigilant in keeping the expectations of gender equity on an upward trajectory.

For me, I am committed to focusing my attention into two areas that can and will make a difference in my own community. First, I am dedicated to speaking and advocating for gender equity in leadership positions in the arts – even if it is uncomfortable, difficult, and frustrating. Second, I will continue to program compositions by female composers on each of my concert performances. So far, this has been successful, and my hope is that this will become the norm for other musical ensembles.

It is almost 2017 and I am stunned by Ricky O’Bannon’s article, “The 2014-15 Orchestra Season by the Numbers,” and Sarah Baer’s more recent article, “Works by Women in the 2016 Season.” While O’Bannon states that only 1.8 percent of total pieces performed by the top twenty-one major American orchestras in 2014-2015 were by women composers, Baer states more troublingly that fourteen of our country’s top twenty-one symphony orchestras did not program a single work by a female composer. This is unacceptable. Our culture should expect gender equity and if it is not happening, then we as musicians need to do something about it.

The presidential primaries brought up a LOT of fascinating quandaries concerning gender and, perhaps unsurprisingly, it is clear that our culture continues to prefer male leadership (1). In order to keep our changing society moving forward, we must continue to recognize and address gender bias as women increasingly enter historically masculine leadership positions.

My intention here is to address gender through a musical lens. In Western classical music, men have long dominated the fields of both composition and conducting. Additionally, until “behind the screen” auditions became the norm starting in the 1970s for American symphony orchestras, men also dominated instrumental positions in those ensembles (Goldin & Rouse, 2000)(2). So, what does this mean and what might we consider as we move towards gender equity?

In my research, “Gender and the Symphonic Conductor,”(3) I found that the lack of female leadership in the symphonic world mirrors precisely the lack of female leadership in the corporate world. Women currently hold 3% of CEO positions in Fortune 500 companies. Similarly, women hold 3% of orchestra conducting positions in the top 52-ranked music conservatories in the world, as well as 4% of music director positions in the top 50 budgeted orchestras in the US. This vast gender disparity in critical teaching positions at the university level and powerful music director positions at the professional level shows that these institutions are not capitalizing on the enormous potential of the female population (which is half of the population).

The purpose of my study was to explain why so few women occupy leadership positions in symphonic conducting and to develop tools that may help women better succeed in this field. I included three components: student interviews from the Pierre Monteux School of Conducting (2012); professional conductor interviews, with both men and women; and surveys of professional symphony musician concerning gendered leadership.

My research can be summarized in these six conclusions:

- Women should embrace their gender distinctiveness and tap into positive gender leadership qualities that allow women to portray themselves in a confident and comfortable manner;

- Women should understand different types of leadership skills and how these skills are perceived in order to add to their inherent leadership styles;

- Women conductors may find their optimal strength concerning confidence in front of an orchestra from a balanced, strong, and centered body with clear visual connections with musicians;

- Women must question whether they are being trained adequately;

- Women must be cognizant of how they dress, as they will be judged on their appearance;

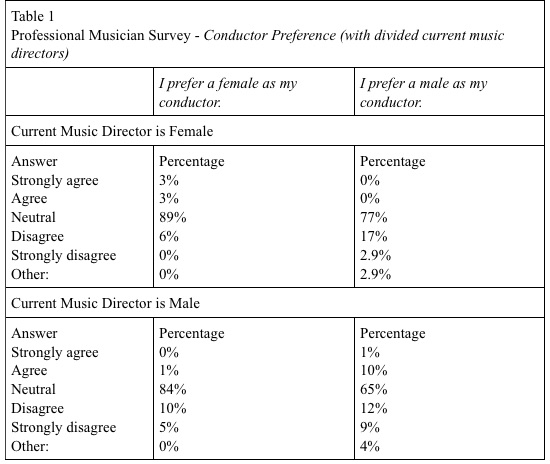

- Finally, professional musicians did not have a gendered preference for conductor after they had the opportunity to work with a female music director. (4)

In a phone interview with the highly regarded conducting pedagogue Gustav Meier, he emphatically stated, “The main thing is that there is no difference between the men conductors and the women conductors. There is no difference.” (5) Although I believe his heart was in the right place, I respectfully but emphatically disagree. We DO have differences. You can see and hear these differences. You can see our differences by the way we dress, by the gestures we use, by the gender we choose to identify ourselves with. You can hear the differences by the way we talk, by the way we problem solve, and by the way we connect with people.

If women are going to move successfully into the higher echelons of our various musical fields, our culture must provide adequate mentorship for women, so they can thrive as leaders in our field. Further, our culture must promote women, to become the half of our music industry that has been missing. When this happens, our entire musical profession will benefit.

Let’s talk about perception. A friend of mine, who is concertmaster of a major orchestra, explained gender perception of conductors best. He said, “The biggest difference between a male and a female conductor is how they are going to be perceived. Not necessarily that female conductors tend to do this or male conductors tend to do that. It’s that when they do what they do, it will be perceived differently.” Why is this? Men and women both can be expressive and charismatic conductors, yet research shows us that our perceptions are different for men and women.

In her well-known book, Lean-In, Sheryl Sandberg states, “Success and like-ability are positively correlated for men, but success and like-ability are negatively correlated for women.” This is an astounding and profound observation! To rephrase, the more successful a man is, the more people like him; but the more successful a woman is, the more people dislike her.

Social scientists have documented this surprising reality in many studies . For instance, in 2002, Frank Flynn, associate professor from Columbia University’s Business School, tested the idea of gender inequity. Flynn provided the portfolio of a successful business executive to his students and then had them take an on-line survey, to rate their impressions. Half of the class received information for Heidi Roizen, who is an actual venture capitalist business executive based out of Silicon Valley. The other half of the class received the same exact portfolio, with only one small, but incredibly important change. This half of the class received “Howard Roizen’s” portfolio — the same exact portfolio, only the name and the pronouns were changed.

As you might expect, students felt Heidi and Howard were equally competent and effective. What I found fascinating was that students didn’t like Heidi. They wouldn’t hire her. They wouldn’t want to work with her. They disliked her aggressive personality. The more assertive they felt she was – the more harshly they judged her. However, this was NOT true for Howard. Students wanted to work for Howard. They liked Howard because he was a strong leader and he knew how to get things done. The pronouns were significant: people’s perceptions were noticeably biased based solely on the gender of the subject.

I believe that change will happen when we pay attention to these gender inequities that permeate our culture. We must become aware, attentive, and honest about what is going on around us, and insist on policies promoting diversity of leadership in top musical organizations and institutions. These institutions are highly visible and people pay attention to them; thus their governance and artistic leadership have a broader cultural significance. Their leadership needs to demonstrate that they are aware of the inherent biases of our society, and that working for diversity and equity is the right thing to do.

Business models show us that companies with at least one female in a leadership role significantly outperform organizations without females in these positions. (6) The same holds true for our orchestras. My research emphasized that the biases against women dissolved once a woman was actually in a leadership position (See Table 1). (7)

These findings strengthen expectation and insistence for greater numbers of women in both our major symphony orchestras and major music universities and conservatories. Gender equity in leadership positions is a healthy and beneficial ideal, which will bring about innovative strategies, and encourage different ways of creative thinking. A professional musician resonates this musical possibility:

When performing with a female or male conductor, I don’t think of them in terms of gender. We’re communicating with each other through music, and that’s the focus of our relationship. It’s an intimacy that is beyond interacting with each other based on gender. It’s like having a close friend from another culture or ethnicity. You don’t think of them in terms of their culture or ethnic background, you think of them in terms of your friendship. You’re beyond thinking of them in simple terms. The complexity and intimacy of a friendship and a musical relationship bring the parties involved to a much higher plane than just gender. Once I get to know someone, they no longer appear to me in those terms or with those labels (Professional musician, Professional Musician Survey). (8)

Each conductor brings his or her musical views, interpretations, gestures, and personalities. With each varying musical personality – new repertoire, interpretations, collaborations, and season programming will evolve.

I leave you with five critical questions:

- Could you be gender biased? Given the structure and history of our society, and the gendered expectations that continue in all walks of life, it is hard not to be. Sometimes the first step towards healthy change is an honest look inward.

- Could these biases getting in the way of what you see and hear in musicians?

- Are organizations that you serve (such as musical institutions, workshops, or competitions) providing equal opportunity for all genders?

- Are the educational institutions that you are affiliated with providing gender equitable programming? If not, are you willing to speak up?

- How will you best mentor and encourage more women to make a positive difference in our field?

We need to capitalize on what women can offer our industry, but more importantly, we need to recognize and be proactive about why things are taking so long to change. We must be open to encouraging, developing and promoting women to mitigate gender bias. Let’s start the conversation!

NOTES

(1) Gallup Poll (2013) – Americans’ Preference for Gender of Boss, 1953-2013

(2) Goldin, C., & Rouse, C. (2000). Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of “Blind” auditions on female musicians, American Economic Review, 90(4), 715-741.

(3) Edwards, A. (2015). Gender and the Symphonic Conductor. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/33213

(4) Edwards, A. (2015). Please see data from musician survey, p. 126-7.

(5) Meier, Gustav. Personal interview. Aug 31, 2014.

(6) McKinsey’s research, Catalyst research, Deloitte Australia research

(7) Edwards, A. (2015) Gender and the Symphonic Conductor. p. 127

(8) Edwards, A. (2015) Gender and the Symphonic Conductor. p. 280