VAN Magazine of Germany recently published this interview with two key figures of the Women’s Orchestra Project of Berlin. Author Merle Krafeld kindly gave permission for a translation to be published here. Liane Curtis and Laura W. Macy have edited the Google Translation. The original article is here.

“This is the sea I want to swim in” — The Women’s Orchestra Project brings unknown works from bygone eras to the stage, as well as world premieres—all created by women composers. By Merle Krafeld

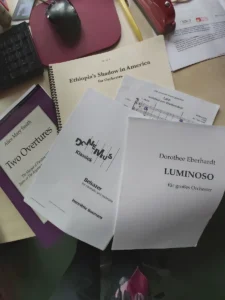

All photos © B. Hoffmann

March 8, 2023

“We’ve known each other for 48 hours,” explains conductor Mary Ellen Kitchens at the beginning of the workshop concert of the Women’s Orchestra Project (Das Frauenorchesterprojekt–FOP), and she makes a sweeping movement in the direction of the more than 80 musicians who are squeezed onto the Astrid Lindgren stage of the FEZ in Berlin. This suggests a lower bar than what they actually achieve. Under Kitchens’s direction Alice Mary Smith’s overture to “Masque of Pandora,” hangs together even after this brief rehearsal: the dynamics are finely differentiated and the dramatic outbursts revive those who are a bit sleepy on this Sunday morning. Only the occasionally shaky intonation is a reminder that the majority of the musicians are ambitious amateurs. The program also features music by Florence Price and Barbara Heller, as well as two world premieres: Dorothee Eberhardt’s Luminoso and Michaela Dietl’s Walsa fantastica for accordion and orchestra. And: Henriëtte Bosmans’ Belshazzar for alto and orchestra (after the ballad by Heinrich Heine), which will most likely be heard at this concert for the first time since its premiere in 1936. The aim of the FOP is to make audible as much music by women as possible: the repertoire currently includes 56 works, the earliest dating from around 1770; the most recent was edited the evening before the concert. “In English, you would say we’re a ‘reading orchestra,’” explains Kitchens after the concert. “It’s about reading a lot of literature, getting listening impressions.” In addition to the FOP, the conductor leads several other orchestras and choirs, works in the archives of the Bavarian Radio and volunteers with the International Working Group on Women and Music, the sponsoring association of the Archives of Woman and Music (Archiv Frau und Musik) in Frankfurt am Main. She plans the respective programs for the FOP in consultation with a team of nine musicians. The threads run together with orchestra organizer and FOP oboist Beatrice Szameitat. Everyone works here on a voluntary basis, with great dedication. “Hearing is Believing. The listening impression touches you, you want more!”

I’m meeting Mary Ellen Kitchens and Beatrice Szameitat after the concert. They are exhausted but in a relaxed mood. The “Du” (informal version of “you”) is offered immediately.

Mary Ellen Kitchens and Beatrice Szameitat

The Belshazzar soloist Merlind Pohl

VAN: How is it that Henriëtte Bosman’s Belshazzar, is being performed today 87 years after it was written?

Mary Ellen Kitchens: I read everything I can find about female composers from morning to night; I can’t help myself. And so I just found Belshazzar in Bosman’s list of works. There was probably a performance of this work in the 1930s. Why else do you write a work like this? But we have quite likely heard today the first performance of this piece in the current time.

Beatrice Szameitat: With Belshazzar I saw the sheet music and thought: “Let’s see.” And when it started with this gloomy mood and these crazy chords, I was completely enthusiastic.

Kitchens: I have been fascinated by the biography of Henriëtte Bosmans for some time. She often wrote specifically for soloists with whom she had a personal connection. Her early works are for cello, which she wrote for Frieda Belinfante. There are eyewitness interviews online with this cellist and she talks about “Yetti,” about her relationship with Henriëtte Bosmans when she was young. After that Bosmans was in a relationship with a violinist, then there are works for violin, and later in life for voice.

How do you decide which pieces to play?

Szameitat: The most important thing is the personnel. We started out as a very small orchestra, with 17 women. We have over 80 now. That’s why we’re dependent on large, late romantic music or modern music. It is also important to us to launch new works, to look for music that has actually never been performed, including older ones, for example in the Archiv Frau und Musik. It’s really important to me that we bring these pieces to light that are hiding in some drawer. For the Persephone Overture by Imogen Holst, for example, we received scans of her handwriting from the Britten Foundation in England to play from. Our performance of this work may have been the first one..

Kitchens: It was the same with Imogen Holst: I read the list of works and found a Persephone Overture that suited our forces well. And then I started researching finding the music for it.

Was there a discovery at FOP that was particularly momentous in that the piece ended up on other programs as well?

Kitchens: Emilie Mayer, for example, is becoming more and more popular. The orchestra has had a connection to Mayer from the very beginning, because the founding mother of the orchestra, the double bass player Gudrun Schnellbacher, found Mayer’s third symphony in the State Library here in Berlin. Although she played in several orchestras, no one else wanted to try it, probably on the grounds that the composer was too unknown. Schnellbacher then edited the symphony with Tobias [Fasshauer] and founded the FOP to play it movement by movement. In the meantime, the symphony has also been published by Furore Verlag, but there was already an edition from the FOP that you could play from.

Szameitat: We also had a playable version of Vilma Weber von Webenau’s Overture Zum Goldenen Horn, which hasn’t been released yet either, but it would be great if someone else were to play it. We also notice that the many FOP players, who come from all over Germany, take their FOP experience out into the world.

Kitchens: One of our musicians, Fanni Mülot, is the first chairman of the Hessian section [LHLO] of the Federal Association of Amateur Music Symphony and Chamber Orchestras [BDLO], so FOP is connected to the BDLO to a certain extent. And at the BDLO the sheet music database is now being revised so that female composers can be found much more easily.

Is there an openness among amateurs for music by female composers? I sometimes have the feeling that particularly familiar works are often programmed in these kinds of groups, in order to bring people into the ensemble who “finally want to play Beethoven themselves.”

Kitchens: I always divide making music in an orchestra into three types: professional orchestras, the independent scene, and amateurs. In the independent scene there is the greatest openness, they want to present something new. In the professional orchestras there are those who say: ‘We have to bring the big war horses, because that’s why people come, especially after this difficult Corona virus period.” And others say: “Right now is the time to move forward. Few come anyway, even if we present the standard works. So let’s do something new!” It might not necessarily be the A-orchestra who act like this, but rather B and C. I recently spoke to Joseph Bastian, for example, the new head of the Munich Symphony Orchestra, about repertoire suggestions because he wants to play music by women composers.

In the amateur field I sometimes still have to do some convincing on behalf of female composers, but I incorporate at least one piece by a female composer into every concert I conduct. In my next concert with the Kempten Orchestra Association I’ll be doing the Unfinished (Symphony by Franz Schubert), but also Rain, Steam and Speed by Cecilia McDowall—a piece that I got to know at FOP.

One of my orchestras has this musician on the board who is rather resistant: “Another female composer? I don’t even know that piece.” A really great musician, but a bit skeptical. And recently I got an email from him: “Do you know this symphony by Amy Beach?” [laughs] I would like to program her Gaelic Symphony very soon.

Of course there are also amateurs who want to break the canon, maybe commission new pieces and work closely with the composer—why not?

[The BDLO announced a composition competition for its 100th anniversary in 2024.]

Playing the music of female composers and making it better known is a very plausible basic idea. Why is it important to you to only play with women?

Szameitat: It’s simply the genesis of the project that these 17 women got together in 2007. When I first joined, I noticed that there is a great atmosphere among women. I’ve been thinking for a long time about exactly what that is and I still haven’t quite figured it out. It’s just a safe space. Some attach great importance to it, while other female musicians would also play with men.

Kitchens: The FOP is definitely a women’s networking place. And it’s also about feeling the power we have.

Szameitat: We notice that there are also women on the tuba and the timpani. Yesterday we suddenly had to fill the tuba position, even that worked out!

What changes have you observed in the last 16 years, i.e. since the founding of the FOP, in terms of female composers in today’s concert life?

Kitchens: In the meantime, thank God, there are quite a few numbers and benchmarks: Studies like those by Melissa Panlasigui or Donne – Women in Music by Gabriella Di Laccio.

Szameitat: The Donne study from 2022 [which analyzes the programs of 111 major orchestras from 31 countries] showed that only around 7 percent of works being performed are by women composers. That’s a depressing number, of course. But I also have the impression that things are changing.

Kitchens: There’s even an orchestra [the Chicago Sinfonietta] in Chicago, directed by Mei-Ann Chen, that programs half its music with works by women. There is a certain momentum, which makes me very happy. If we ask how many FOP musicians play pieces by women in their home orchestras, there’s a difference compared to three years ago – maybe a third this time: Price, Mayer, Farrenc, Clara Schumann, Smyth… I already have the impression that there is a kind of new canon formation with these now better-known female composers. We have to show how broad the work of women composers is, and also refer to artists like Elfrida Andrée or Imogen Holst. With repertoire from America, and South America in particular, there is still a lot to discover: we played Chiquinha Gonzaga, Elsa Calcagno… I found a list online of all the symphonies by women composers. A guy in Wisconsin who is actually an astronomer keeps this list. You can still find a lot there.

There are also more and more good recordings that are also on the radio, which is also important. And, a massive number of female composers have also just been added to the ARD pronunciation database!

The scores of this year’s FOP concert

What roles do associations like FOP or the Archiv Frau und Musik play in this development?

Kitchens: With the Archiv, we notice that there are many more research requests: “We want to program female composers, what is there?” Of course we are willing to help, that is one of our main services. But we actually need more staff. And that’s a good sign. Here, too, it is more the independent orchestras that make inquiries or do extensive research themselves, in Germany for example the Ensemble Reflektor, Operation der Künste, the Frankfurt Chamber Philharmonic, the Leipzig Free Orchestra…

Most of these ensembles are quite young – do you also see a kind of generational change in the FOP?

Kitchens: Since it started in 2007 and partly still in the spirit of the second women’s movement, we have a higher representation of older generations here, people – actually one should say: personalities – who identify with them. We still have that vigor of the 1970s and 80s, I don’t want to exclude myself from that either. But we are definitely intergenerational and a lot of younger musicians are there too.

Szameitat: This time there are a lot of new people who came from outside, about half of the musicians. We are now thinking about expanding the brass section from double to triple.

If you could name a piece that should be played more, what would it be? [– Both consider for a moment]

Kitchens: We already have favorite female composers, [Grażyna] Bacewicz for example. Her Concerto for String Orchestra is one of the greatest modern works, and it is being played more and more. But her four great symphonies (which are still preserved) should also be performed! We played her second symphony, and there is no recording of it on the market yet.

Szameitat: It was just super intelligently composed, funny, colorful music, it just sparkled. We were all on the edge of our seats!

Kitchens: I think that’s how she lived. There’s a quote from her that says she feels three times faster than everyone else. It also feels very violinistic. And she wrote such fantastic sounds that were completely unheard of for me. After FOP I really longed for it: This is the sea I want to swim in!

Editor’s note: Throughout this article, when composers are mentioned there are links to VAN’s own articles on 250 Women Composers (250 Komponistinnen) — these are beautiful articles, but we didn’t want to link frequently to untranslated content.