By Dr. Liane Curtis

On Dec. 2, 2022 I had the opportunity to hear – more than hear, of course, to experience — the Experiential Orchestra in New York City (you will recall that EXO brought us the magnificent recording of Ethel Smyth’s The Prison, which won a Grammy in 2021). This was not something I was going to miss, particularly when they were offering a historic premiere of Julia Perry’s Violin Concerto.

Titled “An Evening with Curtis Stewart,” we were offered many sides of this engaging artist: instrumental virtuoso, intimate communicator, composer and arranger, often in motion with his violin. “Louisiana Blues Strut” by Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson was the program opener. Originally for solo violin, here the string ensemble encircled the room with a gentle but energizing accompaniment, while Stewart moved with a dancer’s grace, weaving in and out amongst the audience. It was up-close in a way classical music so rarely is; the simple, rectangular, wood-paneled space of the DiMenna center was the perfect venue. My concert-going companion, used to vast halls and high stages, whispered to me wide eyed “I’ve never seen anything like this!”

Stewart’s technique was effortless, and because of his ease with the ensemble, virtuosity was never the subject, but rather a tool to convey the musical expression. His introspective, rap-infused arrangement of Ellington /Strayhorn’s “Take the A train” (with the refrain on the violin) was an intense soliloquy on personal identity “…. I am my mother’s son — but nobody owns me” — explored with subtilty revealing Stewart as poet, as well as the composer of the counterpointing accompaniment. These and other meditations are found on Stewart’s Grammy-nominated (2021) album “Of Power.” It was one of those nominations that provoked controversy, since anything in a “classical” category carries the expectation that rap elements will not be included. Awards like the Grammy are given with certain categories, boundaries that can be – and need to be – pushed and explored.

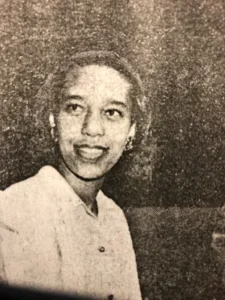

Dr. Fredara Hadley

To introduce Julia Perry (1924-1979) before the performance of her Violin Concerto, Stewart and Music Director James Blachly brought forward Dr. Fredara Hadley, Ethnomusicologist and Juilliard professor, to join with them in discussing Perry’s life. Perry’s musical career began with auspicious successes, but ended sadly, even tragically. Her professional trajectory reached such heights certain to place the composer securely in the ranks of the most recognized and rewarded – but instead, she was mostly forgotten. Hadley noted this trajectory as a tendency for other Black women of the era, terming it “the precarity of success.” She mentioned Shirley Graham Du Bois, whose opera “Tom-Tom” was performed to audiences of 20,000 in 1932– yet despite this acclaim, Graham Du Bois was forgotten, and her opera “Tom-Tom” survives only in an incomplete piano-vocal score (a recovery effort with performance excerpts, from 2018 is here).

Composer, Julia Perry at home in Florence. (Photo by David Lees/Getty Images)

Perry graduated from Westminster Choir College, (where she served as concertmaster of the orchestra), won two Guggenheim awards, Tanglewood fellowships, and studied with Nadia Boulanger and Luigi Dallapiccola. Conscious of – and proud of – her role, she wrote “Composer” on her passport – the passport doesn’t ask for profession! Her “Study for Orchestra” and “Stabat Mater” were both recorded. Publishers were responsive at first, but then seem to have lost interest. A Black woman, composing abstract modernist music – that might catch attention for a while, but then, because for many her work must have been perceived as an impossibility, a cognitive dissonance, interest in her work eroded. The white males of her generation who became known as composers, had institutional support (of course there are exceptions to any such sweeping statement). While Perry did teach, these institutions did not become a long-term source of support for her.

When she had a paralyzing stroke in spring of 1970, she lacked the support of an ongoing academic position – of its health insurance and other benefits, as well as consistent peers. She returned to her family home in Akron, Ohio and was cared for by her widowed mother. Blachly observed, if she had had someone to take dictation from her in her illness – as Mozart did in his last days – she would have completed more works. And it is shocking and disturbing to see the long list of her output, with most of her music unknown or even apparently lost.

That she continued to compose demonstrates a steely will and unshakable belief in her creative ability, an inspiring and even heroic determination. And that now people – musicians and scholars — are finally are engaged in the labor-intensive task of finding and exploring her work, it seems she is on the cusp of a dramatic rediscovery. We can note here the important work of the Akron Symphony, who recently premiered Perry’s Fragments from the Letters of Saint Catherine, and who have launched this website, The Julia Perry Project.

Dr. Hadley offered wise advice – “we need to assume that the music exists!” Then, it is much more likely to be found. If you do otherwise – assume there is no music — then it is very unlikely it will be found, even if it does exist. While this might seem like stating the obvious, the assumption of so most music-making is based on completely the opposite assumption: that the music we have and know is the music that exists. So why should we even bother to wonder about other music? That attitude has worked for decades to keep music by women and people of color off of concert programs, out of textbooks, and out of the canon. What an exciting time we are in, to see those assumptions begin to be overturned.

Julia Perry’s Violin Concerto (originally composed 1963- 65, and with revisions made until 1977) is imbued with a rich lyricism, while also employing a dissonant and edgy language. The intervals of a major 3rd and a major 7th are structural elements explored both melodically and harmonically and introduced in the lengthy and restless opening violin solo. A showcase of dramatic, dissonant violin writing, wide leaps imbue the melodies with a restless poignancy, and in the first instance of it reminding me of Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, the solo arcs an expansive series of arpeggios, and then huge leaps, when it is finally joined by the orchestra.

The piece proceeds as with a series of separate panels, perhaps as a passacaglia, with each segment having its own distinct characteristics, and both motivic elements and structural framework linking them together. In one passage, motives are repeated at different pitch levels as part of a terraced structure. In another the violin is the sustained chorale tone while descending leaps move athletically through the orchestra. Then, oscillating and overlapping melodic fragments provide an undulating motion but also a sense of stasis, deeply imprinting the flavor of the dissonant intervals on us. With the ensemble including a saxophone, a piano and a marimba, the instrumental timbre is one of the ways the repetitive elements are recontextualized and elaborated.

Again like Berg, there is a fascination with formal clarity and structure as an element of a poignant expressive language, along with the melodic and harmonic vocabulary. Stewart was a completely poised and committed performer, and Perry, who had been an expert violinist herself clearly knew how to push the limits of the instrument, but in an idiomatic and effective way. The musicianship of the ensemble (with Blachly’s leadership) was absolutely stellar, no small feat in taking on an unknown major work.

The striking solo violin passage is recalled as a cadenza, and builds in a brilliant, determined summation, with the orchestra joining in with dizzying swirls and a final chord of emphatic ambiguity. Capturing a searching angst of the later 20th-century, the rediscovery of this concerto is definitely a landmark.

A hero and leader in this process of historical recovery of Perry’s Concerto is Professor Roger Zahab (University of Pittsburgh)–a violinist, conductor, scholar and composer. Zahab performed the concerto with the orchestra at the University of Pittsburgh in February 2022. This performance was a fulfilment of a promise that Zahab had made to Perry over 40 years earlier! As a “pandemic project” he set to editing the concerto and learning the violin part. Then, with the University of Pittsburgh Orchestra, he made good on his promise! That remarkable first performance can be heard here (and Perry’s own program note is included). After that, the publisher uncovered the version that Perry had continued to revise. So Zahab then revised his edition for the Dec. 2 performance with EXO and Curtis Stewart; that concert was the premiere of the revised edition, the New York premiere, and also the first performance with a professional orchestra. And now we simply hope for many more performances.

The revelation of this concerto was a major event of this or any year!

While the Julia Perry work was the focus of the evening, also on the program was Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s Sinfonietta No. 1 for Strings (1953). This was a New York City premiere, but as was reported in 2020, Perkinson is on the cusp of a rediscovery (and several recent recordings of Sinfonietta No.1 can be heard on Youtube, although the Chicago Sinfonietta recorded it in 2000). Written when the composer was in his early 20s, its beginning with imitative and contrapuntal material might be seen as a statement to command academic respect. But the spiky and acerbic subject grabs the listeners’ interest, while avoiding the splash so often heard in opening gestures. The fugal energy counterpoints soaring melodies and reaches energetic brilliance.

The second movement “Song Form: Largo” spins a spare and evocative melody over a calm substrate (like a chorale) – the entirety coalesces into a meditative simplicity. This was truly a sublime musical moment, buoyed by the exquisite playing. The final movement “Rondo: Allegro furioso” pulses with frenetic energy, which eases in the middle section of a vast calm expanse, but we glimpse this breadth only briefly before the pulsing motion returns, this time with cascading imitation, disjunct and chaotic. The frenetic fugal passages here are punctuated by bass pizzes, followed by a structural return of the opening material, morphed to even higher energy levels.

To close the evening, the ensemble offered Julia Perry’s “Ye who seek the truth” an arrangement of her choral work. It was a moving benediction for a remarkable evening – and for the amazing process that is taking place, the transformation of orchestral repertoire through the recovery of these previously buried and unknown musical treasures.

Further Resources

Women Composition Students of the Tanglewood Music Center

Akron Beacon article on The Julia Perry Project

Akron Symphony, The Julia Perry Project

Humanities Commons Working Group led by Dr Kendra Preston Leonard