It’s our Annual Repertoire Report!

As in years past, we have taken time to look at the concert programming planned by the top 21 American ensembles (as based on their yearly operating budgets). A full list of the ensembles which were included in this study has been included at the bottom of this post. However, the individual plans for the future were not as straightforward as they have been in the past, which complicated the process of analysis. Several ensembles have not yet announced their coming season programming, or have only announced concert plans through the end of the calendar year. The desire for caution is certainly understandable and realistic, as we are a long way off from “normal” even still. The information presented here is valid at the time of this writing, and will be updated as more information becomes available. We look at these specific ensembles as they are seen as leaders and trendsetters in the field – and, with the largest operating budgets, they have the most resources to purchase or rent new or little-known music, fundraise for new commissions, hire additional necessary players, and even to have opportunities to record these works. We fully acknowledge that less affluent ensembles are doing great work in being inclusive and diverse. But we expect more of the ensembles that have less to lose.

The data used for this study was taken directly from press releases or concert calendars on official websites, and included the most recent information at the time of this publication. We did not include any Family, Holiday, Pops, or other special events that are not otherwise included in typical subscription concert packages. For example, several ensembles have exciting chamber music, “new music”, or family programming including works by women that are not otherwise heard during the regular concert season. Though we applaud this inclusion, they were not a part of the given analysis and are therefore not included in these numbers.

Of the 21 ensembles we look at, we only have partial information available from Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. We have no information yet from Minnesota or San Diego

With all of this in mind, let’s have a look at the numbers, shall we?

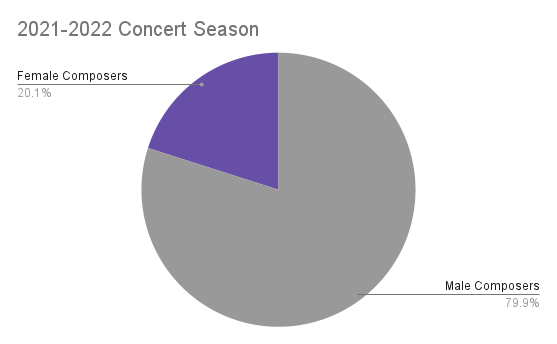

Of the 269 individual composers represented in the information we have thus far, 54 identify as women: 20%, which is the same percentage as last year.

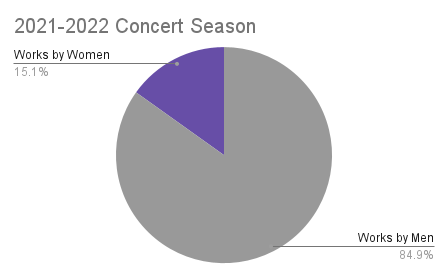

Of the 707 individual works being performed reported, 107 are composed by women. This is a total of 15%, and an increase from the 11% seen last season.

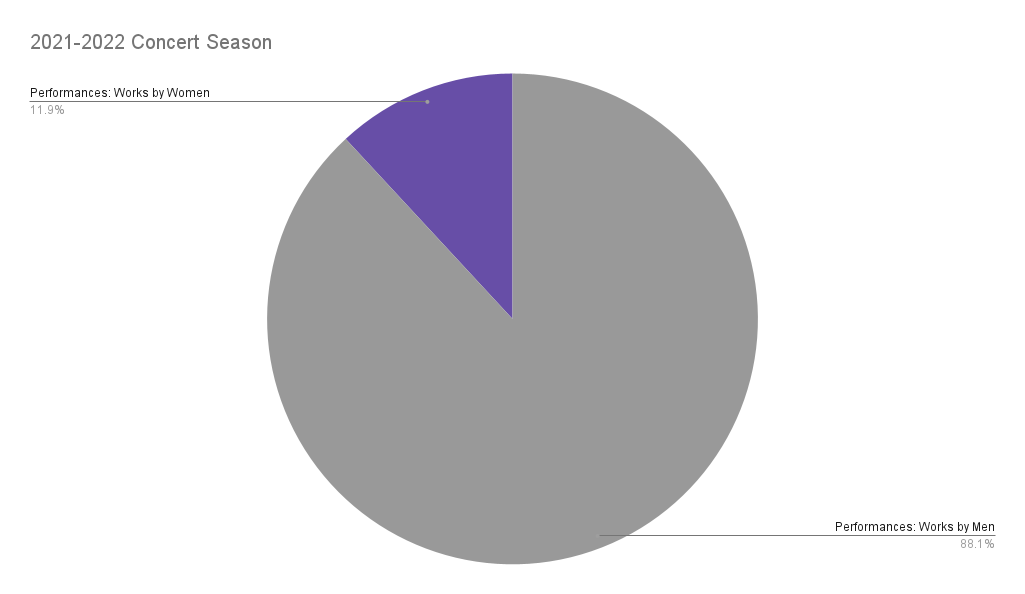

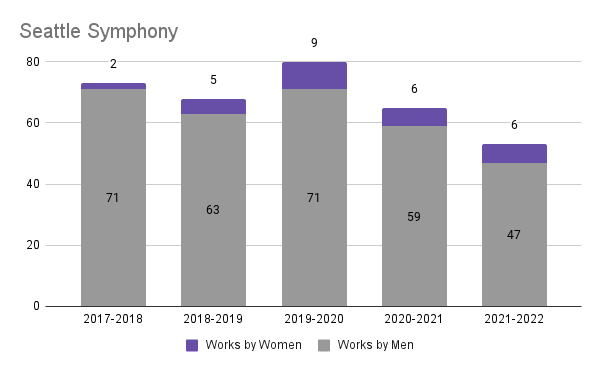

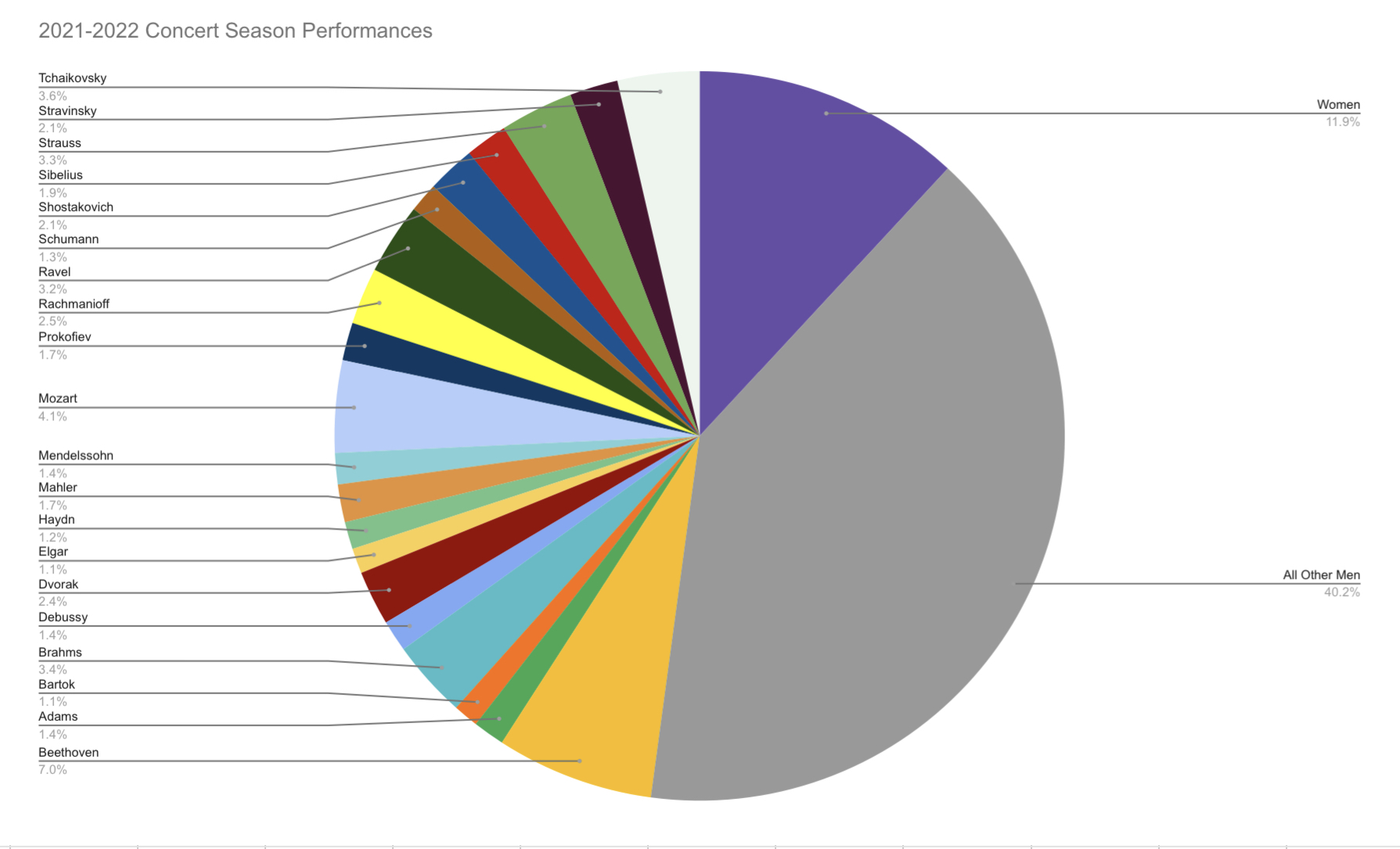

As we have mentioned in the past, the truth of how truly small and over-programed the canon of “great” works becomes overwhelmingly obvious when the total number of performances that take place is taken into consideration. The total number of performances (though not factoring multiple performances of the same program in a concert weekend) was counted as 1076 this season, which only included 128 performances of works by women. This 11.9% is actually significant growth from the 7.8% that we saw in the 2020-2021 season, and the 6.5% in the 2019-2020 season.

Take into consideration that works by Beethoven alone received 75 performances, and works by Mozart received 44 performances. Add Tchaikovsky’s 39 performances to the pile and the works of just three men outnumber the total performances of all the women included throughout the concert season. The works of just 20 dead, white men make up half of all of the programming heard throughout the season.

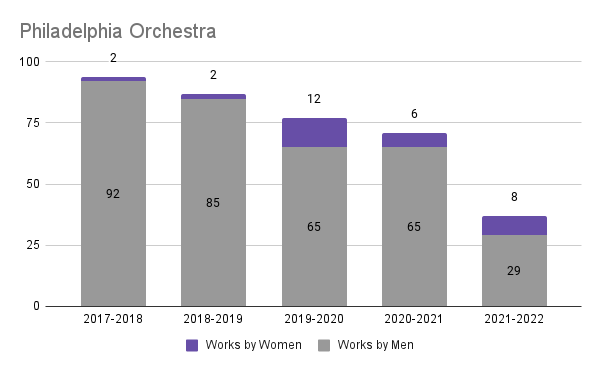

However, when we look at the individual ensembles, and the ways in which the individual programming has changed we can see the way that some ensembles are actively working for change to occur from within their own concert halls. A five-year look back shows how some ensembles are making great strides, while others are seemingly content to tick off the “token woman or two” quota on each year’s program. Particularly notable is the work being done by the New York Philharmonic and Philadelphia Orchestra. More on that, and how each ensemble measures up, below.

One of the areas that we at WPA are particularly vocal about is the need for inclusion not just of the rising star, contemporary composers, but to include the works of great historic composers who are not longer around to advocate for their own works. It was refreshing to see so many historic women included in the programing, with the woman to receive the most performances being Florence Price, whose works will receive a total of 11 performances. The women composers being heard are:

- Julia Adolphe

- Grazyna Bacewicz

- Amy Beach

- Mel Bonis

- Lili Boulanger

- Nadia Boulanger

- Angelica Castello

- Chen Yi

- Unsuk Chen

- Anna Clyne

- Valerie Coleman

- Ruth Crawford Seeger

- Natalie Dietterich

- Melody Eotvos

- Reena Esmail

- Louise Farrenc

- Gabriela Lena Frank

- Vivian Fung

- Sarah Gibson

- Sofia Gubaidulina

- Amanda Harberg

- Jennifer Higdon

- Hannah Kendall

- Hannah Lash

- Fang Man

- Ziboukle Martinaityte

- Missy Mazzoli

- Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel

- Misato Mochizuki

- Jessie Montgomery

- Angelica Negron

- Nokuthula Ngwenyama

- Elizabeth Ogonek

- Gabriela Ortiz

- Younghi Pagh-Paan

- Julia Perry

- Florence Price

- Ellen Reid

- Kaija Saariaho

- Clara Schumann

- Caroline Shaw

- Nina Shekhar

- Arlene Sierra

- Gabriela Smith

- Sarah Kirkland Snider

- Outi Tarkiainen

- Andrea Tarrodi

- Augusta Read Thomas

- Anna Thorvaldsdottir

- Joan Tower

- Gloria Isabel Ramos Triano

- Melissa Wagner

- Xi Wang

- Ellen Taaffe Zwilich

We also look at who is conducting each ensemble, in particular because the gender disparity in conductors in these ensembles is particularly disproportionate. There are a total of 127 conductors leading the ensembles throughout the coming season, in some way: whether they are single-night engagements, or primary roles. That includes 15 women – only 10.6% of the total number of conductors. If we look at the numbers in a bit more detail – and consider who is conducting what – there is more information that adds to the perhaps not-so-complicated story of why more works by women are not actively being programed and performed.

The women conductors at the podium for these top ensembles this coming season are:

- Marin Alsop

- Karina Canellakis

- Elim Chan

- Dame Jane Glover

- Eun Sun Kim

- Susanna Malkki

- Gemma New

- Anna Rakitina

- Ruth Reinhardt

- Dalia Stasevska

- Nathalie Stutzmann

- Shi-Yeon Sung

- Lidiya Yankovskaya

- Simone Young

- Xian Zhang

In the coming season women conduct 128 of the 1076 performances – a total of 11% of the total performances, and – ironically – the same number of total performances of works by women will be heard. However, women conductors are conducting a disproportionate 20% of the total performances of works by women composers. It seems as though a natural consequence of more women at the baton turns out to be more music by women composers on the music stands.

The calls for diversity and inclusion have led to more this just a slight increase in the number of works by women composers being performed. This coming season will also include performances of works of composers of African descent, including Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Anthony Davis, William Dawson, Chevalier De Saint-Georges, Xavier Foley, Adolphus Hailstork, James Lee III, William Grant Still, and George Walker, in numbers unseen before. It seems as though the calls for racial justice and the conversations surrounding the white supremacy of classical music has made at some sort of impact on program directors. Yet, these voices combined with the Black women listed above (Florence Price, Julia Perry, Jessie Montgomery, Valerie Coleman, and Nokuthula Ngwenyama) constitute just a fraction of the overwhelming dominance of the Canon that is still dominated by white men.

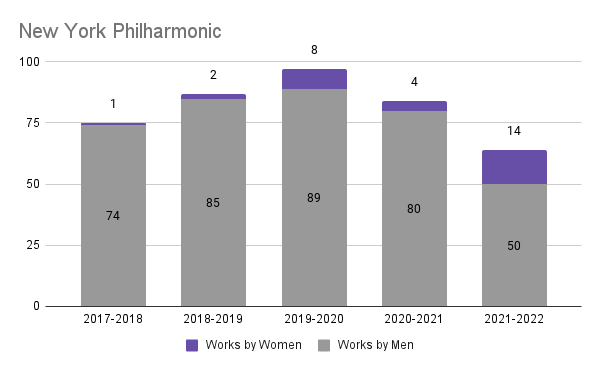

There is hopeful news in that some ensembles are making great effort to be inclusive. Take, for example, The New York Philharmonic:

The New York Phil has turned their eyes to promoting the works of women since their commissioning project in honor of the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment. However, the 14 works that they will be performing this coming season – a total of 22% of their total programming – include long awaited premieres from Project 19, as well as historic works, like Clara Schumann’s Piano Concerto, Ruth Crawford Seeger’s Andante for Strings, and Julia Perry’s Study for Orchestra, as well as more contemporary works that are also not premieres. Chen Yi’s beautiful Duo Ye and Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) will also be heard. All of which begs the questions: why now? Why not sooner? What made this enormous change in programming suddenly attractive and feasible when it wasn’t before?

The Philadelphia Orchestra, though they only published part of their season programming, has an equally impressive 22% of their programming dedicated to women, at least thus far.

The Fantastic Philadelphians have also decided to dedicate part of their season to what they’re calling Philly Digital, to continue to extend their accessibility to their wider community (and, in fact, the world). Their performances will include a world premiere from Amanda Harberg, Florence Price’s Third and Fourth Symphonies, and Valerie Coleman’s wind quintet being performed in a subscription program.

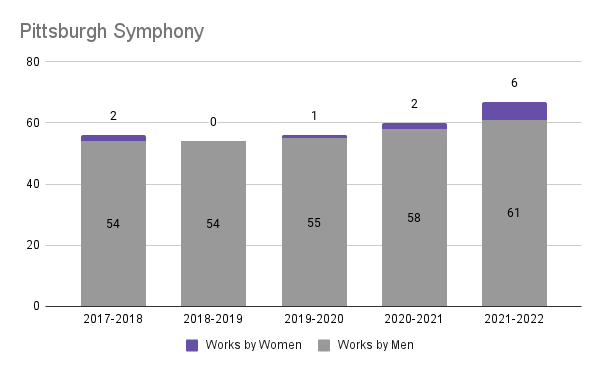

The Pittsburgh Symphony should receive an award for “Most Improved” as they work diligently to be more inclusive:

Women constitute 9% of their coming season, with works by Saariaho, Louise Farrenc, Vivian Fung, Missy Mazzoli, and Jessie Montgomery.

Women constitute 9% of their coming season, with works by Saariaho, Louise Farrenc, Vivian Fung, Missy Mazzoli, and Jessie Montgomery.

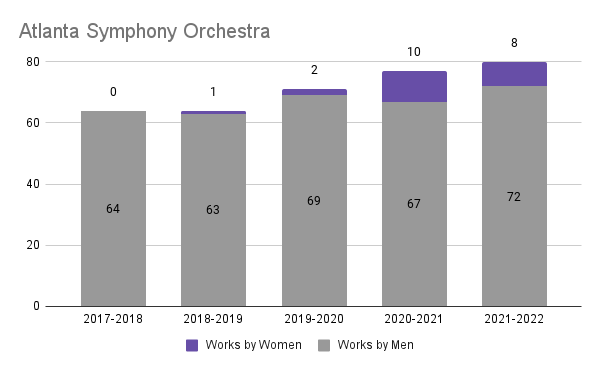

The Atlanta SO will perform works by Florence Price, Jennifer Higdon, Anna Clyne, Jessie Montgomery, Lili Boulanger, Missy Mazzoli, Melody Eotvos, and Sarah Gibson as they include women for 10% of their programming.

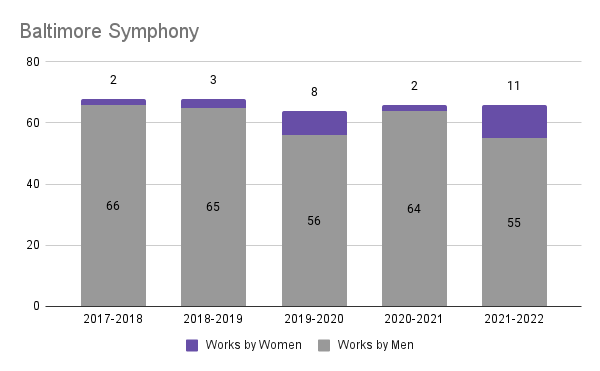

Perhaps it’s telling that The Baltimore Symphony is devoting so much time to women’s voices in Marin Alsop’s final season with the ensemble. They will perform women for 16.6% of their programming, with works by Andrea Tarrodi, Valerie Coleman, Anna Clyne, Clara Schumann, Angelica Castello, Grazyna Bacewicz, Hannah Kendall, Reena Esmail, Jessie Montgomery, and Vivian Fung.

Perhaps it’s telling that The Baltimore Symphony is devoting so much time to women’s voices in Marin Alsop’s final season with the ensemble. They will perform women for 16.6% of their programming, with works by Andrea Tarrodi, Valerie Coleman, Anna Clyne, Clara Schumann, Angelica Castello, Grazyna Bacewicz, Hannah Kendall, Reena Esmail, Jessie Montgomery, and Vivian Fung.

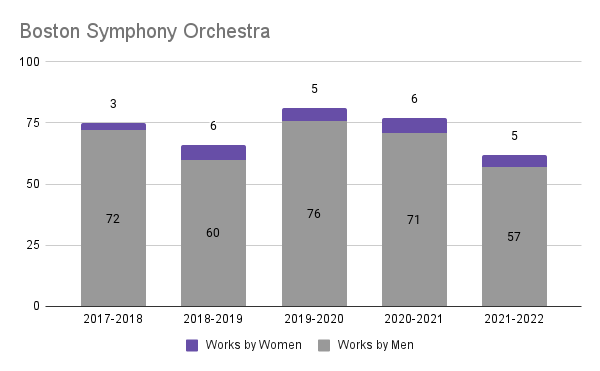

Always one of the more conservative orchestras – and true devotees of Beethoven – Boston is only performing works by four living women: Julia Adolphe, Kaija Saariaho, Unsuk Chin, and Ellen Reid. They make up 8% of total programming.

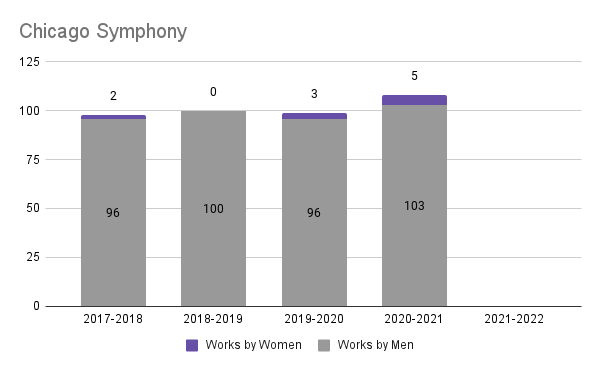

We are curious to see what Chicago will plan for the rest of their season, especially as it was the home of Florence Price, and the ensemble that first premiered her work. Missy Mazzoli just finished her tenure as Composer in Residence, stepping over for Jessie Montgomery to begin her position.

We are curious to see what Chicago will plan for the rest of their season, especially as it was the home of Florence Price, and the ensemble that first premiered her work. Missy Mazzoli just finished her tenure as Composer in Residence, stepping over for Jessie Montgomery to begin her position.

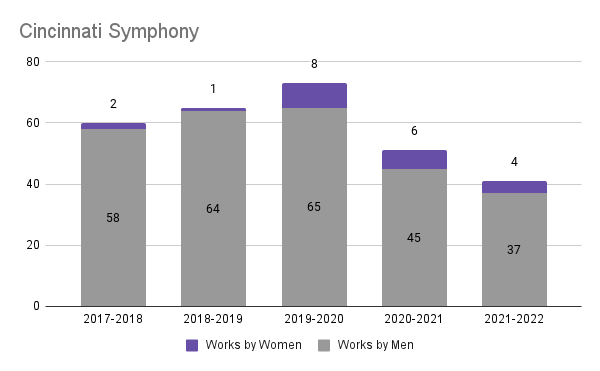

Cincinnati is also performing only works by living women: Augusta Read Thomas, Missy Mazzoli, Julia Adolphe, and Gabriela Ortiz. With such a small season, those four works make up about 10% of the season.

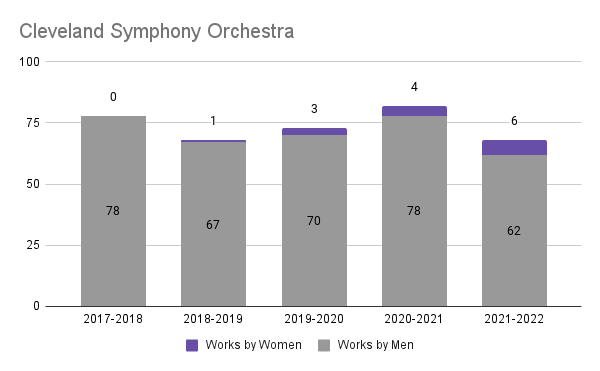

I suppose Cleveland belongs the same credit as Pittsburgh for slow, steady change. Though, for the record, we are also very much in favor of rapid, thrilling changes, too! They are playing Gabriela Smith, Lili Boulanger, Unsuk Chin, and works by Sofia Gubaidulina. Women make up about 9% of the programming.

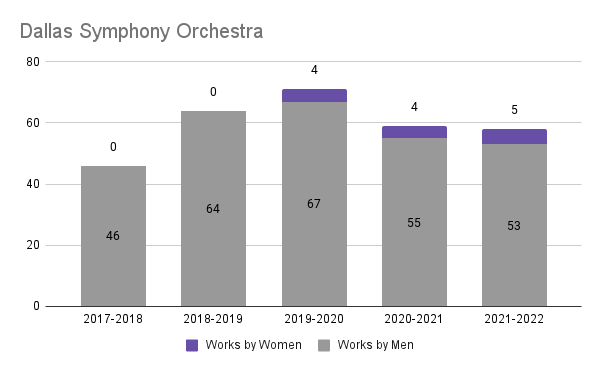

Perhaps the most surprising ensemble for lack of progress is Dallas – especially as Dallas hosts the Women in Music Symposium and Conducting Institute for Women, annually. They, too, are performing works by living composers: Joan Tower, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, Unsuk Chin, Xi Wang, and Jessie Montgomery, but no historic ones. Women make up 8% of the programming.

Perhaps the most surprising ensemble for lack of progress is Dallas – especially as Dallas hosts the Women in Music Symposium and Conducting Institute for Women, annually. They, too, are performing works by living composers: Joan Tower, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, Unsuk Chin, Xi Wang, and Jessie Montgomery, but no historic ones. Women make up 8% of the programming.

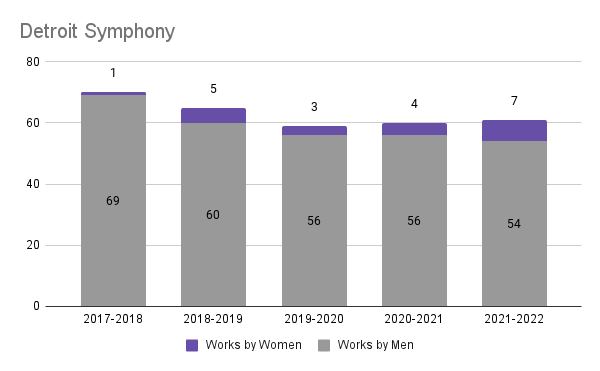

Detroit’s programming offers a great mix of contemporary and historic: Clara Schumann, Jessie Montgomery, Florence Price, Joan Tower, Mel Bonis, Hannah Lash, and Elizabeth Ogonek. Detroit is including women in 11% of the programming.

Detroit’s programming offers a great mix of contemporary and historic: Clara Schumann, Jessie Montgomery, Florence Price, Joan Tower, Mel Bonis, Hannah Lash, and Elizabeth Ogonek. Detroit is including women in 11% of the programming.

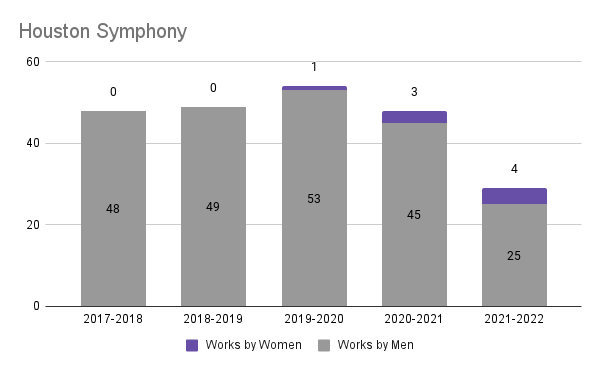

Houston is including women in 13% of their programming and, interestingly, is including works from both Nadia and Lili Boulanger as well as Kaija Saariaho and Jennifer Higdon.

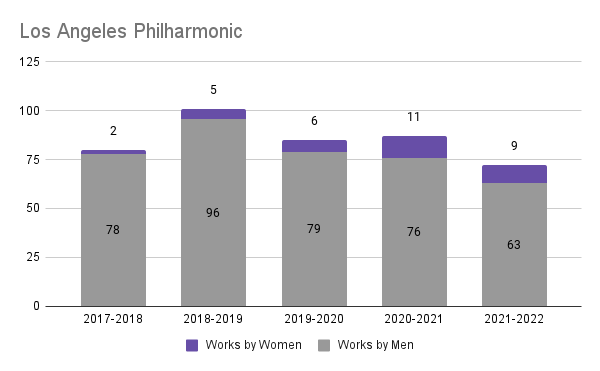

Los Angeles has always been on the leading edge of inclusivity, which is why I am surprised by the decrease of works by women compared to last year. Even still, women make up 12.5%. They’ll perform Jessie Montgomery, Kaija Saariaho, Julia Adolphe, Nokuthula Ngwenyama, Elizabeth Ogonek, Gabriella Smith, Gabriela Ortiz, Angelica Negron, and Anna Thorvaldsdottir.

Los Angeles has always been on the leading edge of inclusivity, which is why I am surprised by the decrease of works by women compared to last year. Even still, women make up 12.5%. They’ll perform Jessie Montgomery, Kaija Saariaho, Julia Adolphe, Nokuthula Ngwenyama, Elizabeth Ogonek, Gabriella Smith, Gabriela Ortiz, Angelica Negron, and Anna Thorvaldsdottir.

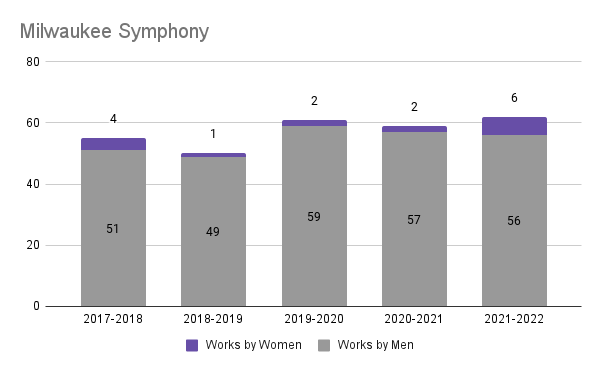

The Milwaukee Symphony will include women in 9.6% of their programming: Anna Thorvaldsdottir, Gabriela Lena Frank, Sarah Kirkland Snider, Florence Price, Misato Mochizuki, and Jessie Montgomery will be heard.

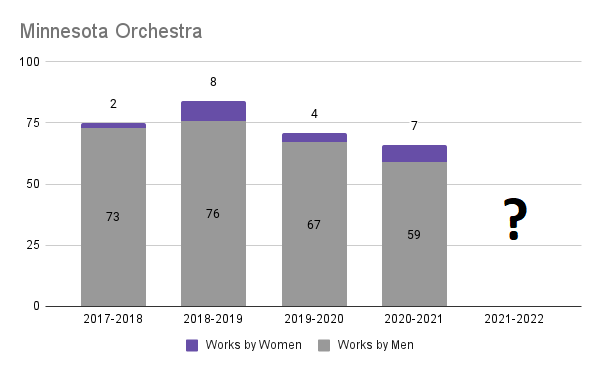

With the range of inclusivity over the past four years from Minnesota, it will be interesting to see what direction they take in the coming season – especially as they watch other orchestras announce their own decisions. Could some positive peer pressure perhaps help encourage the administration to be more diverse and inclusive in their programming?

With the range of inclusivity over the past four years from Minnesota, it will be interesting to see what direction they take in the coming season – especially as they watch other orchestras announce their own decisions. Could some positive peer pressure perhaps help encourage the administration to be more diverse and inclusive in their programming?

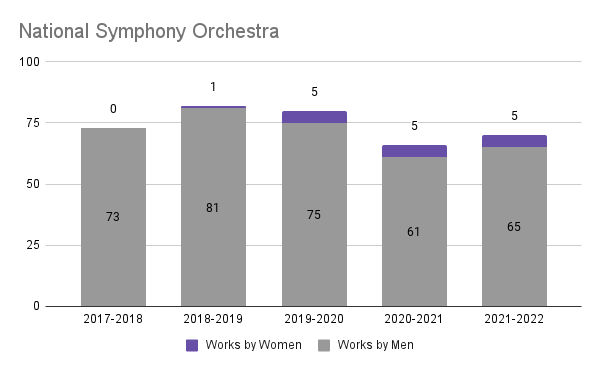

The National Symphony Orchestra, and their instance on five works by women a year for the past three seasons, is a point of interest. This 7% of their overall programming will include, for this year at least, works by Florence Price, Angelica Negron, Missy Mazzoli, Louise Farrenc, and Joan Tower.

The National Symphony Orchestra, and their instance on five works by women a year for the past three seasons, is a point of interest. This 7% of their overall programming will include, for this year at least, works by Florence Price, Angelica Negron, Missy Mazzoli, Louise Farrenc, and Joan Tower.

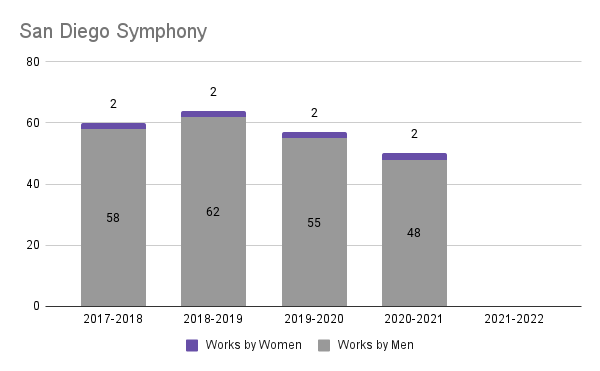

The same phenomenon exists also with the San Diego Symphony. I’m so curious to know if trend will continue for a fifth year!

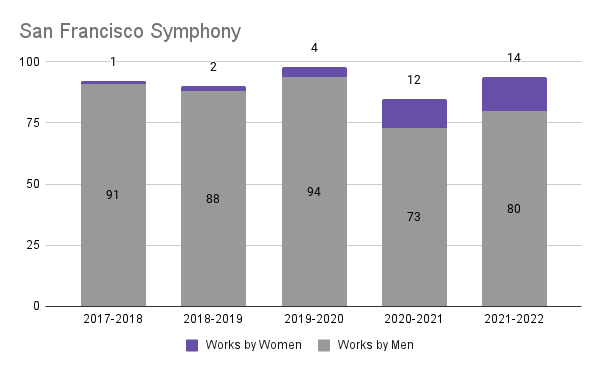

If Boston is one of the most conservative, perhaps San Francisco can be considered as one of the most progressive. Their fourteen works (a total of 15% of their programmed works) includes works by Hannah Kendall, Unsuk Chin, Kaija Saariaho, Anna Clyne, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Younghi Pagh-Paan, Florence Price, Fang Man, Elizabeth Ogonek, Nokuthula Ngwenyama, Lili Boulanger, and Jessie Montgomery.

If Boston is one of the most conservative, perhaps San Francisco can be considered as one of the most progressive. Their fourteen works (a total of 15% of their programmed works) includes works by Hannah Kendall, Unsuk Chin, Kaija Saariaho, Anna Clyne, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Younghi Pagh-Paan, Florence Price, Fang Man, Elizabeth Ogonek, Nokuthula Ngwenyama, Lili Boulanger, and Jessie Montgomery.

The Seattle Symphony has been doing great work in recent years in giving American premieres of forgotten works. The 11% of programming that includes women includes works by Natalie Dietterich, Hannah Lash, Amy Beach, Florence Price, Ellen Reid, and Angelica Negron.

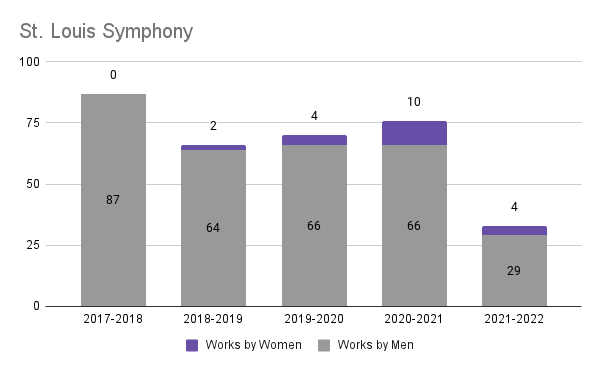

The St. Louis Symphony has yet to announce their full season, but the four works by women they have announced will makes up 12% of their programming. They will perform works by Caroline Shaw, Joan Tower, Outi Tarkiainen, and Anna Clyne.

The St. Louis Symphony has yet to announce their full season, but the four works by women they have announced will makes up 12% of their programming. They will perform works by Caroline Shaw, Joan Tower, Outi Tarkiainen, and Anna Clyne.

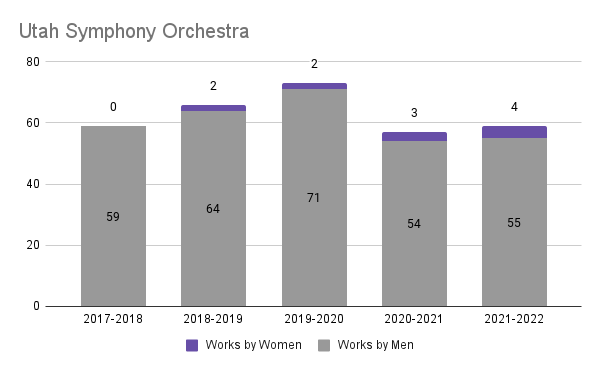

Utah Symphony Orchestra & Opera will perform women in a total of of 6.7% of their programming. They will perform works by Arlene Sierra and Gabriela Lena Frank.

Utah Symphony Orchestra & Opera will perform women in a total of of 6.7% of their programming. They will perform works by Arlene Sierra and Gabriela Lena Frank.

We can’t point to any one reason, decision, or circumstance that may have influenced the minds of decision makers – whether it was a change of heart, or a temporary concession. Though the trends seem to be moving in the right direction, moving at the current pace will mean agonizingly slow change that the community cannot possibly withstand. Change is necessary in order to thrive. It is imperative for the classical music community – for these leading organizations – to recognize the past injustices, including the blind worship of “great” composers while ignoring dozens and even hundreds of others of equal talent, and work to correct those wrongs. The change that is necessary involves being deliberate in programming inclusively and embracing the music, the composers, and the histories that have been dismissed out of hand because they did not fit the preconceived narrative of what classical music is or should be – and who it is or should be for.

We at WPA will continue our work to keep an eye on the programming happening throughout the country – celebrating inclusion when we see it, and calling out the deliberate ignorance when necessary. As we advocate for the voices of women composers to be heard, we also advocate for their stories to be told, their histories to be remembered, and their art to be valued. These women deserve to be part of the conversation, history books, and concert programs that inform our culture and inspire future creators.