While several other organizations now produce reports on the programming by orchestras in regard to diversity of composers, WPA started with our annual report in 2008, and we have consistently focused on the same set, the top level of U.S. orchestras. This provides detailed information on their change (or lack thereof) by these ensembles over the years and also on the women composers whose works are included. Our approach reveals some long-range tendencies. What we would hope to find is a consistent and determined commitment to diversity and not just to replicating (more or less) the same status quo. It takes more than just a few composers or a few instances now and then to create systemic change.

By Sarah Baer

After two-and-a-half years of canceled, shortened, or virtual seasons, it seems as though much of professional music-making in the United States – and around the world – is finding a new rhythm and approach to the new normal. As I collected data for our annual repertoire report I was hopeful that the positive aspects of innovations that we’ve experienced could continue. We have seen more accessible price points and virtual concert experiences that can be enjoyed regardless of location, and also the recent spotlights on the need for change in the classical music community as a whole — with momentum to move beyond the idea of the “great” composer and instead to embrace the rich diversity that has always been a significant factor, and that continues through the present. I wondered if these changes would have an impact on the programming that is planned for the 2022-2023 season.

There have been some impressive initiatives in recent seasons, largely due to pressure of the #MeToo movement, renewed conversations about social justice as a result of violence against Black and brown bodies, and the pressure to build audiences when the traditional model was not available during lockdown. While these efforts are seemingly impressive, do they represent deep and positive transformation? Or are they a temporary distraction – a performative action with no real substance or deeper intentions driving the necessary systemic change?

Methodology

As in years past, I looked at the top 21 ensembles in the United States (as ranked by annual budgets) and looked specifically at the works programmed for their primary subscription series. Thus, excluded from consideration here were any concerts labeled as Family, Holiday, Pops, or other “special events” not included in typical subscription series. The goal is to look at what a typical concert season includes and sells to the bulk, the mainstay of their audiences. While several ensembles have exciting chamber music, “new music,” or family programming including works by women, as these events are special events and not heard by a majority of the listening audience; thus, they are not included in the data.

All of the information was taken from official press releases, concert calendars, and ensemble websites and was accurate at the time of this writing – and with the understanding that programming can change for various reasons throughout the season.

With all of this in mind, let’s take a look at the numbers.

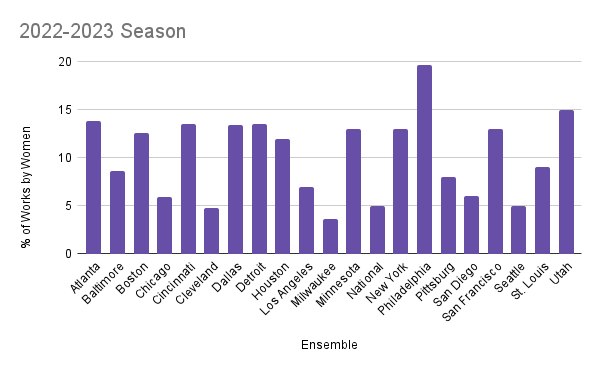

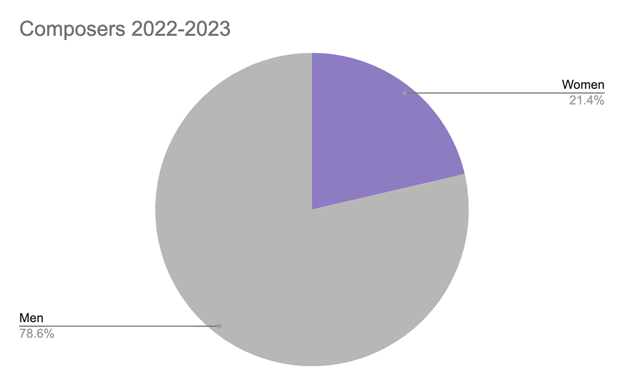

Among the 21 ensembles – who all planned complete programming for the 2022-2023 concert season – 281 composers will be represented, 60 of whom identify as women. This whopping 21% representation is a whole percentage point more than in the 2021-2022 season.

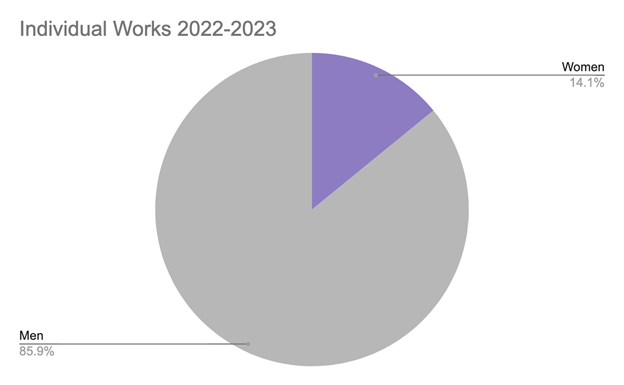

Of the 794 individual works being performed, 112 of the pieces were written by women, a total of 14%. This is a decrease from last season in which we saw 15% of all works being performed having been written by women.

But perhaps the most telling number is the relationship of the number of works to individual performances. For example, each of Beethoven’s symphonies counts as an individual work (Symphony No. 3 counts as one work) and the individual performances is how many times it is performed (in the 2022-2023 season it will be performed by five of the ensembles). Note: when collecting data I only looked at what was programmed, not how many individual performances are given by each ensemble. Some ensembles perform the same program two or three times to accommodate their subscribers, but it is still accounted for only once in the programming data.

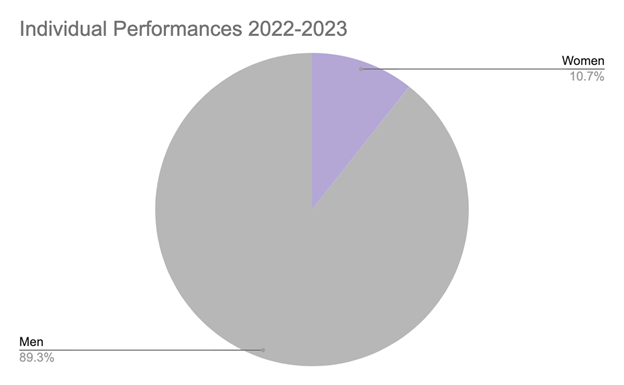

Of the 1344 individual performances of works planned for the coming season, 145 of the performances are of works by women: 10.7% of the total.

This is a decrease from last year’s 11.9%.

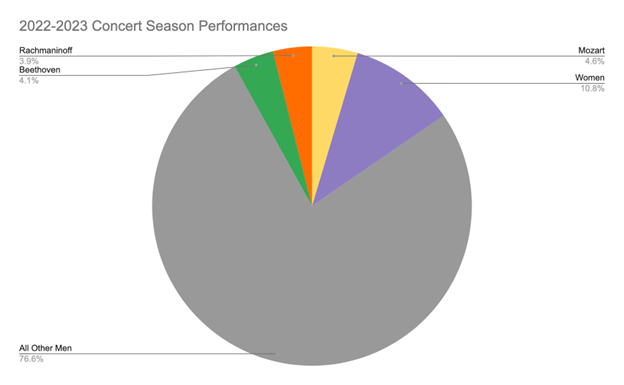

The most performed composers continue to share three things in common: they are all dead, white, men. While American composer and violinist Jessie Montgomery is the first woman and BIPOC individual to appear at the list of most performed composers — at number 22 — the twelve performances she is having this year don’t come anywhere close to the dominance of the traditional “great” composers who continue to take up more than their fair share of the concert programming. Much as with the American economic system, it’s a few people holding the majority of the wealth while the other composers are fighting for their share of the performance time. The top three composers of 2022-2023 – Mozart, Beethoven, and Rachmaninoff – have more performances than all of the 57 women composers put together.

And while it is predominately dead men whose works are heard on US concert stages, the reverse is true for women. While contemporary women – who are actively winning awards, advocating to have their works heard, and networking throughout the industry – receive a significantly higher percentage of performances, it is always exciting to see when historical composers are also included. These trail-blazing women are a vital piece of cultural history and their works receive far too few performances. However, this coming season will hear the work of: Grażyna Bacewicz, Margaret Bonds, Lili Boulanger, Louise Farrenc, Vítězslava Kaprálová, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Dora Pejačević, Julia Perry, Florence Price, Clara Schumann, and Ethel Smyth.

Another hopeful data point was the number of Black composers included throughout the programming – a total of 32 men and women, historic and contemporary, whose works will be heard a collective 97 times. Though still a far cry from the goal, we must remain hopeful in the progress that we see.

However, as we explore the programming for individual ensembles, it becomes evident that the pressure that was felt to address programming concerns has leveled off. Many ensembles are performing fewer works by women this year than they did this past season – even taking into consideration the numerous hurdles that the pandemic threw at the performing arts world.

There are only three ensembles who are performing significantly more works by women in the coming season than were planned for the 2021-2022 season.

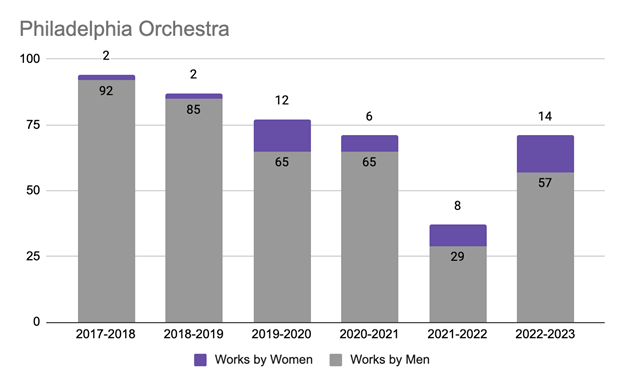

The Philadelphia Orchestra, which received aggressive feedback about their planned lack of representation in the 2018-2019 season (that they immediately addressed by shoehorning in some women composers after the season announcement), has been making significant strides to be more inclusive. The 2022-2023 season will see the most impressive efforts yet, with works by women making up 19.7% of their total season programming.

These fantastic Philadelphians will kick off the season with Valerie Coleman, and include several works by Florence Price. Also heard will be music by Hilary Purrington, Nina Young, Clara Schumann, Xi Wang, Louise Farrenc, Elena Firsova, Lili Boulanger, Andrea Tarrodi, Julia Perry, and Gabriela Lena Frank.

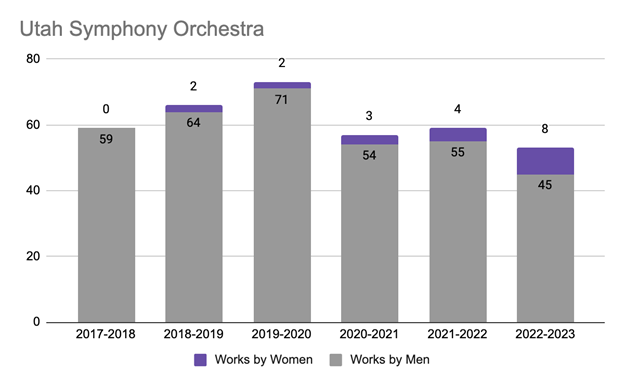

Another ensemble that increased programming efforts was the Utah Symphony. As an ensemble that is historically conservative, the increase in representation is exciting to see. Music by women will make up 15% of their programming in the coming season.

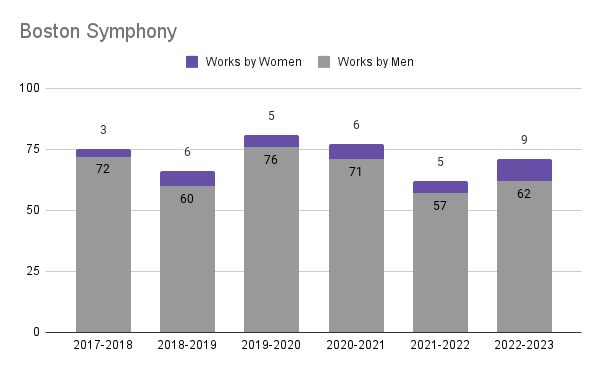

Arguably the most conservative ensemble, The Boston Symphony, has also demonstrated impressive change. They are performing nine works this year, 12.6% of their programming. This includes music by Margaret Bonds, Julia Wolfe, Unsuk Chin, Lili Boulanger, Ella Milch-Sheriff, Elena Langer, Caroline Shaw, Elizabeth Ogonek, and Jessie Montgomery.

The other ensembles, while all including multiple works by women, are largely maintaining the status quo of subscriber (and public) expectations. Though there are some small improvements, it’s not the commitment that we would like to see from these large, prestigious, and affluent institutions that have the funding, personnel, and clout to spearhead the systemic change that the classical music world is calling for.

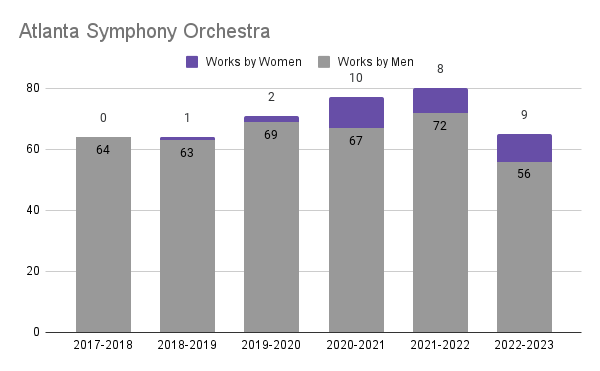

Atlanta’s programming includes women in 13.8% of their programming. I am looking forward to how new music director Nathalie Stutzmann is going to shape the ensemble throughout her tenure. The first work that she is conducting in her new position is by Hilary Purrington, which makes me hopeful for future seasons. Other composers being heard are Jennifer Higdon, Louise Farrenc, Joan Tower, Jessie Montgomery, Anna Clyne, Lera Auerbach, Helen Grime, and Vítězslava Kaprálová.

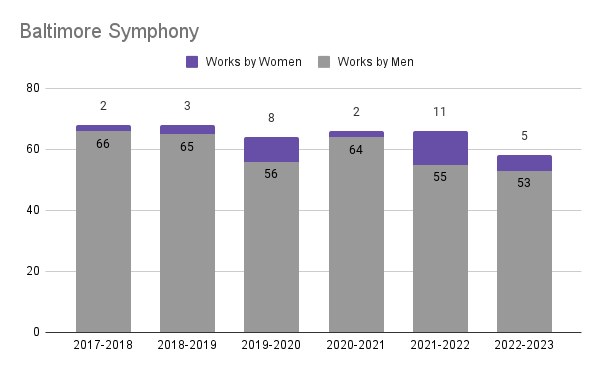

The Baltimore Symphony has women programmed in 8.6% of their programming. This is the first season after Marin Alsop’s departure, and certainly a point of transition. (Though the BSO just announced that Jonathon Heyward has been named the new Music Director, his tenure doesn’t begin until the 2023-2024 season.) The works of Jessie Montgomery, Florence Price, Elizabeth Ogonek, Augusta Read Thomas, and Grace-Evangeline Mason will be heard.

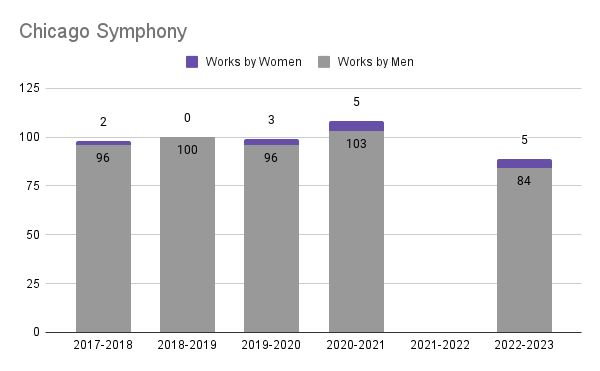

Chicago’s 5.9% of programming is especially disheartening for a city that was the adopted home of Florence Price and also the early home of Margaret Bonds. While they have performed some of Price’s music in recent years, you would think that they would regularly celebrate the amazing legacy of these women! They are performing works by Jessie Montgomery, Nokuthula Ngwenyama, Lera Auerbach, and Julia Wolfe.

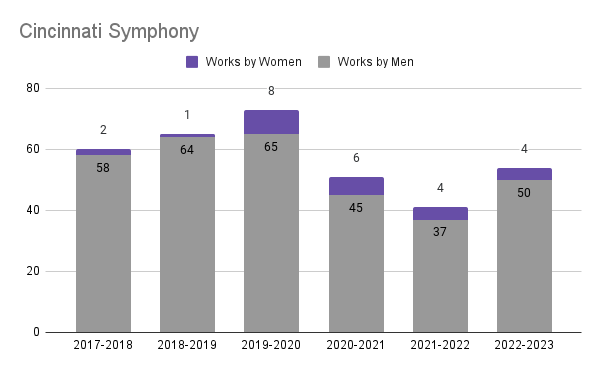

Cincinnati’s 13.5% includes works by Courtney Bryan, Julia Perry, Ethel Smyth, and Missy Mazzoli.

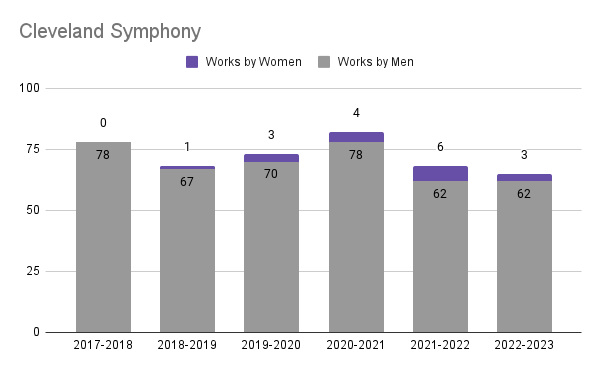

Cleveland’s 4.8% at least includes a work by the historic Louise Farrenc, as well as music by Unsuk Chin, and a newly-commissioned work by Allison Loggins-Hull.

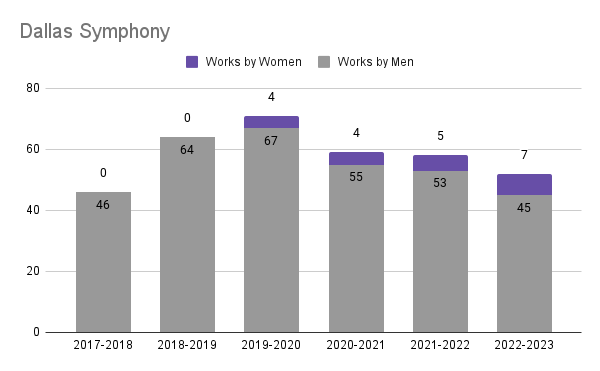

Home of the Women’s Conducting Institute, Dallas has been steadily working towards more inclusion across the stage. Their 13.4% Includes a concert entirely devoted to works by women composers. The women being heard include Angelica Negron, Julia Perry, Clara Schumann, Louise Farrenc, Gabriela Montero, and Katherine Blach.

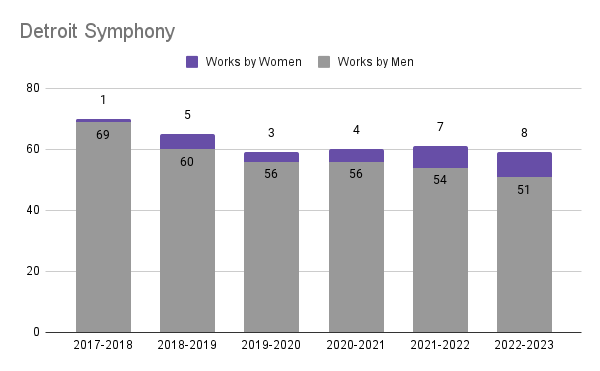

The Detroit Symphony includes women 13.5% of the time. They will perform music by Olga Neuwirth, Florence Price, Tania Leon, Anna Thorvaldsdottir, Anna Clyne, Dora Pejačević, Helen Grime, and Jessie Montgomery. Statistically, Detroit has been showing more-or-less steady but slow improvement.

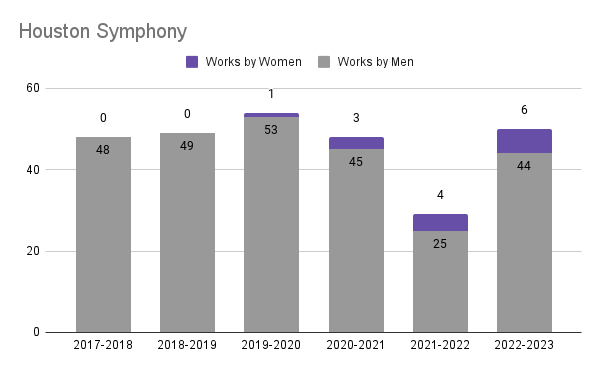

Houston Symphony’s 12% includes music by Elena Firsova, Lili Boulanger, Hannah Kendall, Lotta Wennäkoski, and Louise Farrenc.

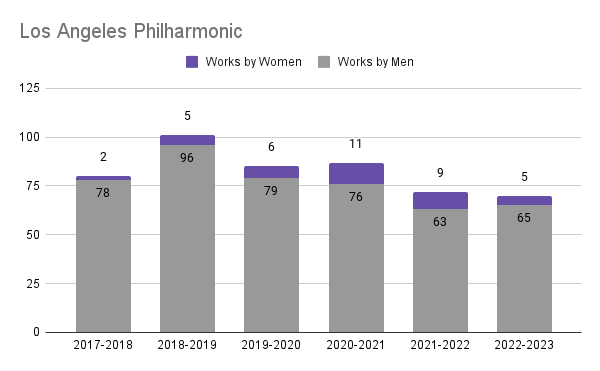

Perhaps most disappointing is the Los Angeles Philharmonic. They are only including women in 7% of their subscription programming – a significant decrease from prior years. They will perform works by Gabriela Ortiz, Helen Grime, Andrea Tarrodi, Anna Clyne, and Anna Thorvaldsdottir.

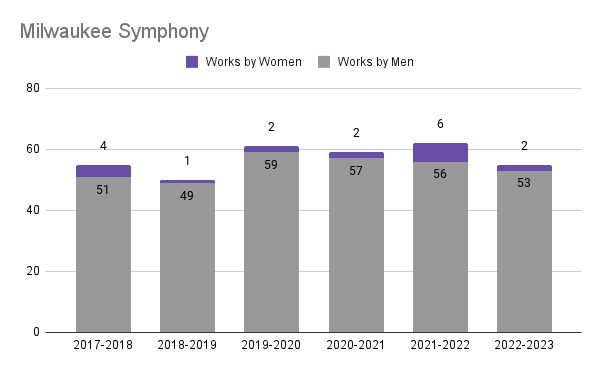

The two works by women heard at the Milwaukee Symphony are by Jessie Montgomery and Helen Grime. That women represent only 3.6% of programming is truly disheartening.

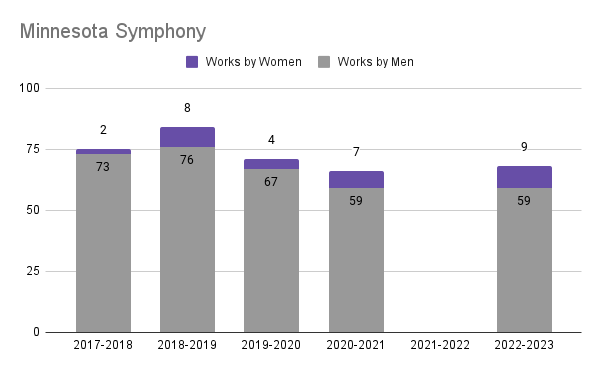

The Minnesota Symphony’s 13% includes music by Lili Boulanger, Jessie Montgomery, Missy Mazzoli, Kaija Saariaho, Hannah Kendall, Eleanor Alberga, and Chen Yi.

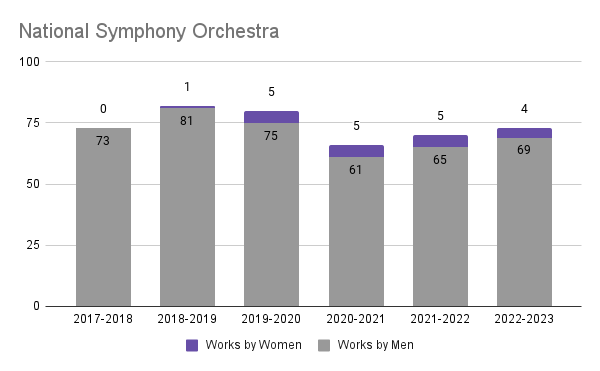

National Symphony’s 5% is also particularly frustrating considering the organization and the resources at hand. Jessie Montgomery, Sofia Gubaidulina, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, and Florence Price will be heard.

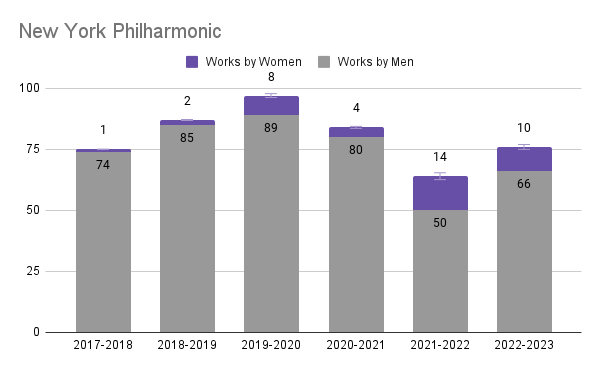

The effects of The New York Phil’s “Project 19” commissioning effort are still unfolding, with several premieres happening in the 2022-2023 season Music by Tania Leon, Caroline Shaw, Florence Price, Kaija Saariaho, Anna Thorvaldsdottir, Wang Lu, Grażyna Bacewicz, Courtney Bryan, Zosha Di Castri, and Julia Wolfe will be performed. The mix of new works and historic pieces brings their inclusion rate to 13% for this season.

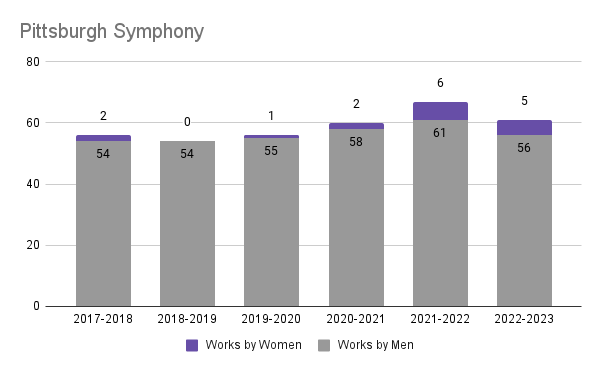

The Pittsburgh Symphony is (at least somewhat) maintaining the progress they made last year. Their 8% of women composers include Joan Tower, Lera Auerbach, Unsuk Chin, Lili Boulanger, and Stacy Garrop.

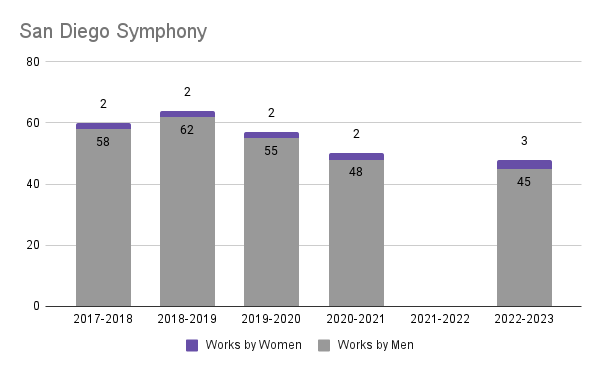

The San Diego Symphony is persistently stubborn in their commitment to doing just enough to not be told that they omit women altogether! I suppose we should be glad that they increased their usual two works by women to a whopping three. Their 6% in the coming season includes Kaija Saariaho, Jessie Montgomery, and Gity Razaz.

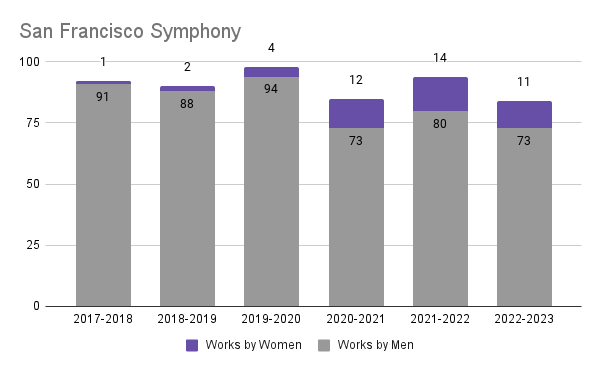

While the exciting momentum we first saw in 2022-2021 appears to have leveled off at the San Francisco Symphony, at least it hasn’t dropped off entirely. Their 13% representation includes Florence Price, Hannah Kendall, Elizabeth Ogonek, Gabriella Smith, Stacy Garrop, Anna Meredith, Julia Wolfe, Gloria Isabel Triano, Reena Esmail, and Margaret Bonds.

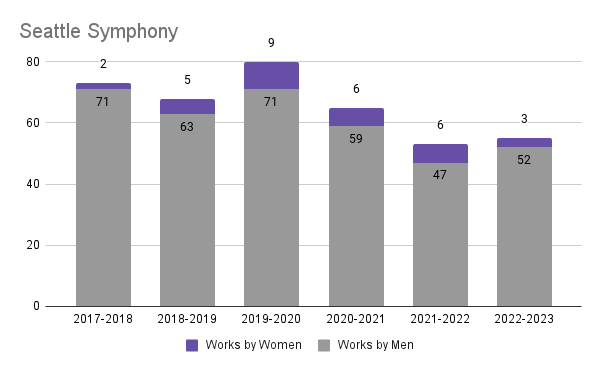

After some tremendous work by the Seattle Symphony in recent years, I am surprised to see so few works by women being programmed there in the coming season. Only making up 5% of their total programming, the three works being heard are by Gabriella Smith, Nina Shekhar, and Salina Fisher.

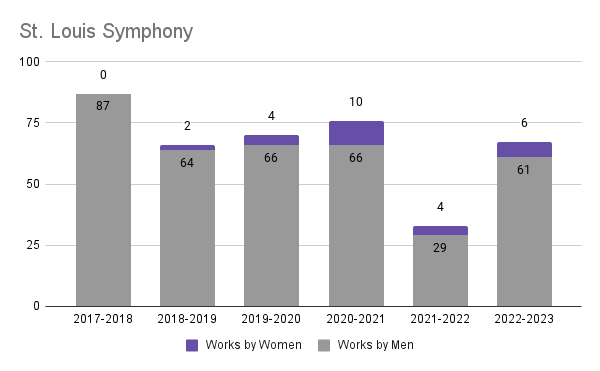

The St. Louis Symphony is including works by women 9% of the time. They will perform works by Nathalie Joachim, Kaija Saariaho, Reena Esmail, Helen Grime, Gabriela Lena Frank, and Nokuthula Ngwenyama.

In total, the coming season for these top 21 ensembles in terms of how they plan to be inclusive looks like this:

While there are some distinct outliers – like Philadelphia with nearly 20% of their programming being women composers, and Milwaukee which comes in as the least diverse and inclusive – we can clearly see that many of these ensembles feel fairly comfortable to sit right around the 13% mark. Again, while this is a huge achievement, especially considering that it wasn’t that long ago that several of these ensembles didn’t perform any works by women in a given season – we are still far off from our goal of truly equitable representation.

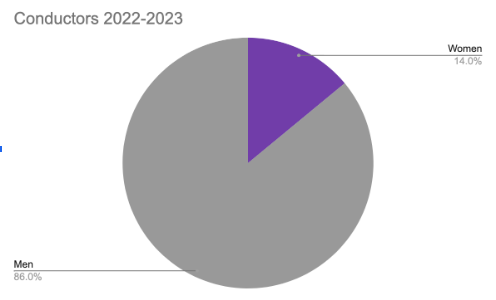

Each year when I sort through the data, I also take a look at who is conducting the works being performed – as women have long fought for equality in the ensembles, at the podiums, and in the programs. These 21 ensembles employ a total of 157 conductors throughout the season, 21 of which are women – a total of 14%.

Of those 157 total conductors, 75 conducted at least one work by a woman composer, but only 30 conducted more than one work by a woman. And even though women only appeared 13% of the time, they conducted 22% of all the performances of works by women. Another factor to consider is that only six women conductors (a total of 28.5% of the women conducting this coming season) are planning to lead zero works by women composers. However, of the 136 male conductors, 76 are not leading any works by women – a solid 55%.

The conductor with the most impressive schedule in terms of number of works being performed is Yannick Nezet-Seguin, Music Director for The Philadelphia Orchestra. He is leading 32 works throughout the season, with a full 25% (eight works) being by women composers. Considering the efforts being made by The Philadelphia Orchestra, this is not surprising. (Though, can we encourage Maestro Nezet-Seguin to bring the same percentage to his work with the Metropolitan Opera?)

The first runner up is Dalia Staevska, who is guest conducting around the country. Of the 25 works she will lead, seven are by women – 28%.

While all of the ensembles performed at least one work by a woman composers, there is a list of conductors who aren’t planning on conducting any, either. While we recognize that this is certainly not always the decision of the conductor (especially when making a guest appearances), there are several names that certainly had the choice and the authority to make that decision, and chose not to. These include: Bernard Labadie, Cristian Macelaru, Edo De Waart, Fabian Gabel, Herbert Blomstedt, James Conlon, Michael Tilson Thomas, Roderick Cox, Sir Donald Runnicles, and Thomas Ades. Other conductors that only led one piece include Gustavo Dudamel, Ken-David Masur, Matthias Pintscher, Rafael Payare, and Riccardo Muti.

With full seasons planned across the country, it very much feels that we are back to “normal”, at least in terms of buying tickets, getting dressed up, and sitting in concert halls. But part of the “normal” that many of us would rather not see again are the exclusionary practices of unaffordable tickets, inaccessible events, and the centuries long propensity for excluding countless composers, performers, and conductors based solely on their gender. As has been evident by the numerous articles and discussion threads posted online, the majority of the classical music world is ready for systemic change. While many of us have been gently, patiently, encouraging change – we also saw what can happen in the wake of calls for social justice and equality. Systemic change does not come quietly in the night, but is the result of direct action taken by those who are passionate for the cause. The data is clear that while progress has been made – and can be made – without pressure from their donors and audience members, no great improvements will be made.

Those of us who love this music, who love this art, and find it not only valuable but in fact necessary for the cultural development and substance of a community, must make our voices heard and understood. We look at these top-budget ensembles because they are a barometer for what is possible when there are no restrictions, but tremendous work can also be done in community ensembles and schools. The progress that we have seen should be celebrated – but also be seen as a stepping stone, as the goal we are seeking is still far off on the horizon. There is still much work to be done.

We invite you to send to your comments on our annual report, and we can include them in an update next week. [email protected]