By Sarah Baer

Even amid all of the chaos and uncertainty – and cancelled seasons – due to the COVID-19 pandemic, ensembles are planning for the future. All major ensembles have released their 2020-2021 season announcements, so we have once again read through, made lists, designed charts, and crunched the numbers. With the continued attention to inclusiveness and diversity in classical music more generally in the recent years – and being all too aware of just how (ahem) conservatively changes occur in the classical music world, I was optimistic (but not overly so) for what would be heard from New York to Seattle with the country’s largest revenue orchestras.

As in past years, the repertoire analysis focused on the 21 ensembles with the largest operating budgets in the United States. (A full list of these 21 ensembles is included at the bottom of this post.) We look at these ensembles because they have the most resources to spend on “new” (or unknown) programming – acquiring music through purchase or rentals, hiring any necessary additional players for the performance, etc. We fully acknowledge that less affluent ensembles are doing great work in being inclusive and diverse. But we should and do expect more of the ensembles that have greater resources and thus less to lose.

The concert listings were taken directly from press releases or concert calendars on official websites and included the most recent information available at the time of publication. We did not include any Family, Holiday, Pops, or other special events that are not otherwise included in subscription concerts. For example, several ensembles have exciting chamber music, “new music”, or family programming including works by women that are not otherwise heard during the regular concert season. Though we applaud this inclusion, they were not a part of the given analysis and are therefore not included in these numbers.

As with last year (the full report of which you can find here) each of the 21 ensembles included works by women. And in the coming season, they can boast that each ensemble performed at least two works by women composers. Several ensembles brought special mention to new commissioning projects specifically for women composers. The New York Philharmonic specifically, is in the midst of Project 19 inspired by the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment and Women’s Suffrage.

Before we dig into more commentary, let’s take a look at the numbers:

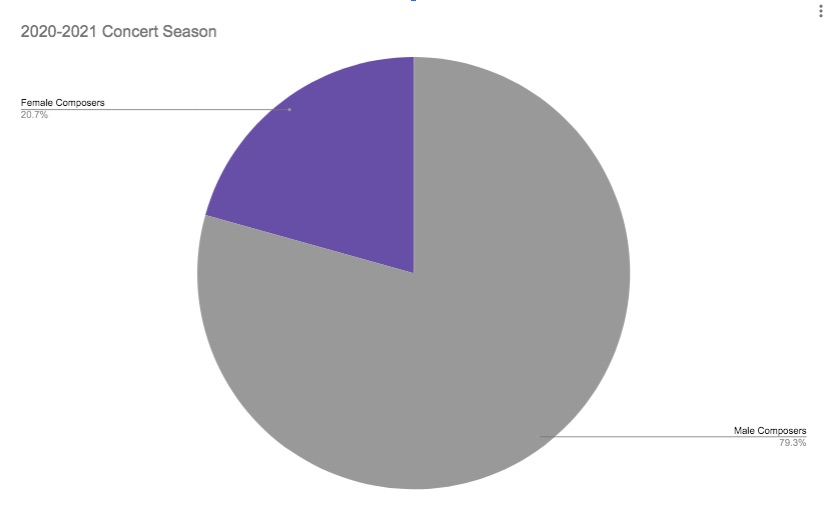

Of the 276 individual composers programmed for this coming season, 57 identify as women. That’s 20%, and only a tiny increase from the 19% that were included in the 2019-2020 season.

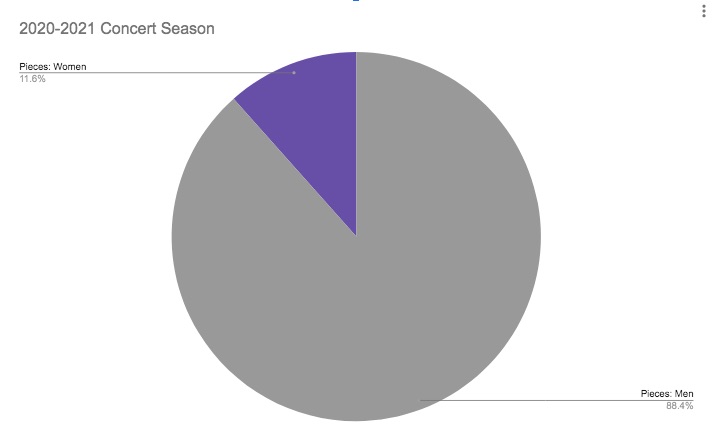

Of the 855 individual works being performed by these 21 ensembles throughout the proposed 2020-21 season, 99 are composed by women – a total of 11.5%. This is actually growth from the 9% of total works scheduled for the 2019-2020 season. And, yet, thisis still frustrating and disappointing.

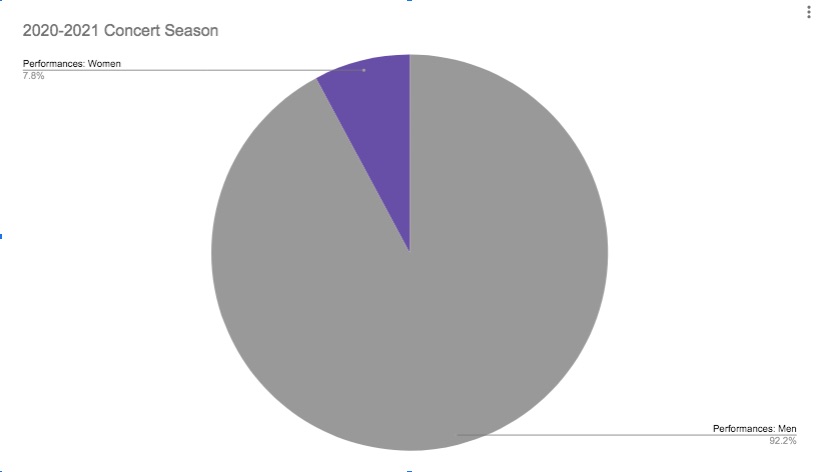

As in years past, the harsh reality of how over-programmed so much of the canon is, is evident in the total number of performances that take place in any given year. The total performances calculated (though not factoring multiple performances of the same program in a concert weekend) is 1455. That includes nine performances just of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 and The Rite of Spring, and 11 performances of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade. The total number of performances by all women combined total 114, just 7.8% of the total. During the 2019-2020 season performances of works by women constituted 6.5%.

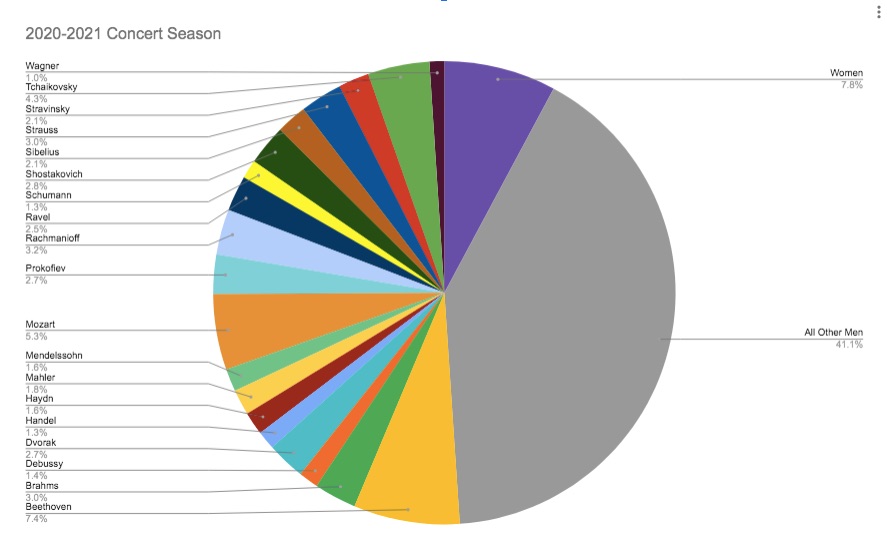

Meanwhile, works by Beethoven alone comprise 108 total performances (7.4%) and works by Mozart alone comprise 77 performances (5%). You can see below how other famous names comprise the most played works, with just 19 dead, white, men making up half of the total performances during this season.

Granted, the works by women composers that are being heard are themselves diverse, including 36 premieres – world premieres and U.S. premieres – as well as 18 performances of works by historic composers. Among the historic works being heard is Clara Schumann’s Piano Concerto, just a year late to celebrate her 200th birthday. Florence Price’s life and works are rightfully being celebrated by several ensembles with performances of her first and third Symphonies and Piano Concerto. Amy Beach’s “Gaelic” Symphony will be performed by the Seattle Symphony – though the work is erroneously listed as “Symphony No. 2” on the website, a mistake first made decades ago by a sloppy publisher, and repeated seemingly without end. Beach only wrote one symphony (and we have the carefully corrected and re-engraved edition available here.)

Some names may be more familiar to regular concert-goers than others. Lili Boulanger is included on several programs, but there are also opportunities to hear Bacewicz’s Concerto for String Orchestra, and Mel Bonis’ The Song of Cleopatra from Three Legendary Women. Listeners will be treated to Teresa Carreño’s Margaritena, as well as Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel’s Overture in C (in a program by St. Louis that contrasts Fanny’s work with Felix’s), and Julia Perry’s A Short Piece for Large Orchestra.

It seems as though some copy writers and marketing professionals are beginning to understand that to attract new audiences, and re-engage disinterested ones, you need to highlight what is extraordinary about any given event. Though there is progress in how concert events are being sold to the subscribers and potential audiences, it is still shocking how many times the selling point of a concert is thought to be the same work heard countless times before. As always, this is not a universal statement, and some ensembles are better than others. But for every good example there are at least two bad, that neglect to mention the unusual work at all, or including the composer’s name only in the final sentence with no context as to why the particular work is of interest and worth hearing.

The champion ensemble this coming season for diverse programming is San Francisco. Of the 85 programmed works, 12 were works by women – a total of 14% of their overall programming, and includes historic pieces, new commissions from up and coming composers, and works from already established living composers. They are also the only ensemble to program a concert entirely of works by women. November 12th and 14th will see Joan Tower’s Sixth Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman, Florence Price’s Piano Concerto, and Julia Wolfe’s new work (and San Francisco Symphony Co-Commission) Her Story brought to the concert hall.

Pulling up the rear are Pittsburgh and Baltimore who each only programmed two works by women. Utah did slightly better programming three, but all from the same, living composer: Arlene Sierra.

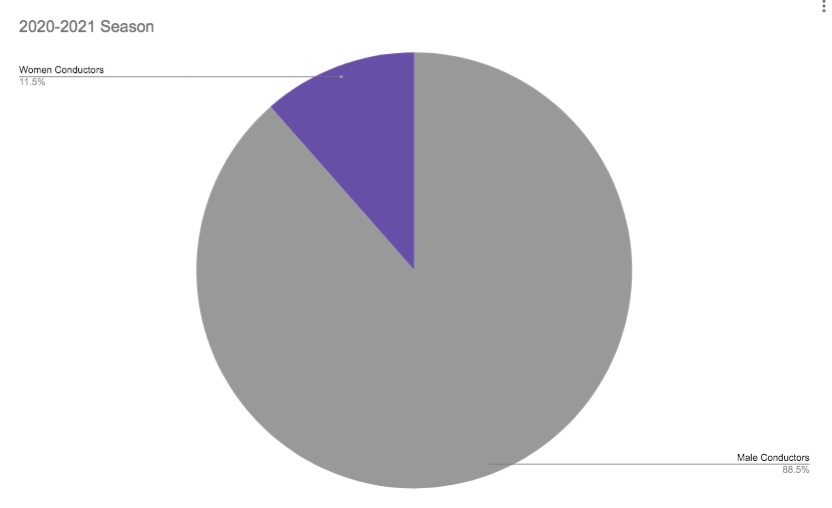

We also took a look at conductors for the coming season. Of the 148 conductors taking the baton this season, 17 are women, which is only one more than we saw last year. Those women are:

Karina Canellakis

Elim Chan

Han-Na Chang

Jane Glover

Lina Gonzalez-Granado

Migra Grazinyte-Tyla

Emmaunelle Haim

Eun Sun Kim

Susanna Malkki

Joana Malwitz

Gemma New

Eva Ollikainen

Anna Ratitina

Dalia Stasevska

Nathalie Stutzmann

Shi-Yeon Sung

Simone Young

These women make up 11% of the total number of conductors, and they will conduct 10% of the music that will be heard, only 149 performances of the 1455 scheduled.

That there has been careful programming in the coming season by all of these ensembles is undeniable. Which, we can assume, means that the social pressure that they have faced in recent years is making an impact. But that should by no means suggest that calls for inclusivity and diversity should be lessened. The progresses that we have seen – slow and laborious as it has been – still has representation of works by women at pitiful levels. The canon is still dominated by dead, white, men, and the celebration of Beethoven’s birthday looks little different from any other concert year.

At the moment, the hard truth is — because of the pandemic — that we are unsure if these seasons will actually happen, or what a concert-going experience is going to look like when it finally does resume. As with so many other areas of our lives, now is a time to reflect, reevaluate, and explore radical thinking. Streaming concerts online makes concerts accessible and affordable to those who are too far, too poor, or too intimidated to attend concerts in person – and before the lockdown occurred, several symphonies experienced tremendous success with an online model. The Met Opera website crashed with so many viewers scrambling to enjoy the free broadcasts they were offering. The audiences are there. And organizations who are willing to take a risk and offer something new will find that audiences are not only receptive, but that those orchestras will be on the leading edge of changes that need to occur for live performances of classical music to thrive in whatever is coming next.

Coming next: Details on the programming