Each year the League of American Orchestras compiles repertoire information from member orchestras from across the country. These ensembles, which range from some of the most outstanding orchestras in the world to regional and youth orchestras, provide this information to the LAO to provide hard information regarding concert numbers, trends, and to reinforce the importance of live, orchestral music in the United States. After compiling this information, the LAO makes available to the public, so it is easy to learn what was heard, and what wasn’t.

The lists are by no means a perfect view into who and what was heard, since they are dependant on the voluntary participation of League member orchestras in submitting their repertoire and are therefore far from complete. They do, however, provide a snapshot into concert halls and performances from across the country. Collecting and analyzing this information is an ongoing project of mine (you can read more about the project and the paper that was presented at the 2009 Feminist Theory and Music conference here). Looking at performance trends gives an opportunity not only to get a better idea for the overall climate, but also to celebrate successes as well as work more effectively toward the progress that, unfortunately, is still desperately needed.

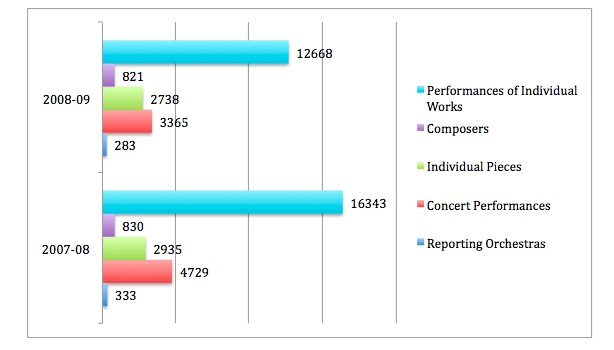

Of course, the 2008-2009 season was a particularly difficult one for all arts organizations, just as it was for all walks of life. The economic collapse meant loss of funding, cut concert seasons, and even disbanded organizations. However, in most cases, despite struggles and uncertainty, the proverbial band played on. The League of American Orchestras had 283 member orchestras report their repertoire for the 2008-2009 concert season. The quick snapshot shows that throughout the season there were 3,365 concert performances, and 2,738 pieces performed by 821 composers; there were a total of 12,668 performances of individual works.

In comparison, for the 2007-08 performing year, 333 member orchestras reported repertoire, with 4,729 concert performances, 2,935 pieces and 830 composers performed; a total of 16,343 performances of individual works. Fifty fewer ensembles reported; 1,364 fewer concerts were heard, with a total difference of 3,675 individual performances not heard.

Even though the LAO provides a wealth of information to any interested person, collecting information on the works by women composers that were heard is difficult. There are many reasons why women composers, and generally any composer who doesn’t fit into the “dead – white – male” categories, are more likely to be heard in smaller/regional ensembles, who are less likely be members of the LAO, or members who chose to not report. (That being said, even large orchestras don’t always report their data – for example, the repertoire reports from the 2008-09 season don’t include any information from the Boston Symphony Orchestra or the San Francisco Orchestra.) However, even if it is less than perfect, this data can serve as an important starting point.

So – let’s have a look!

What is perhaps most striking is the evidence of how limited the standard repertoire is. That there were over 12,000 individual performances but only around 3,000 individual pieces reinforces that it is the same few (though favored) pieces heard throughout the concert season in orchestras across the country.

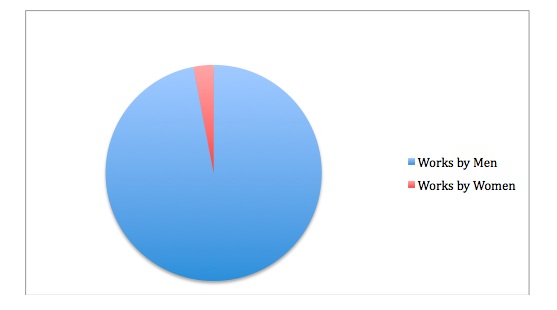

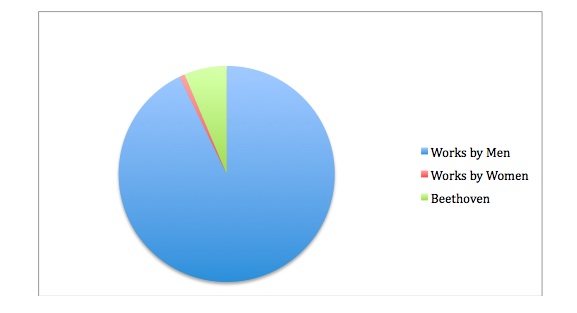

Of the 2,738 compositions performed, 85 were by women – that’s 3%.

LAO reports that there were a total of 12,668 individual performances in the 2008-2009 concert season. Unfortunately, I am unable to accurately determine exactly how many of those performances were of works by women composers. (The repertoire report only lists the first performance date, not any subsequent dates that the piece would be heard in a concert series.) However, I have been able to record a total of 109 performances of works by women – which doesn’t take into consideration repeat performances of the same concert. But even if, theoretically, each ensemble presented two concerts of each program (which is a exaggerated estimation considering the typical budget of a regional orchestra, particularly in such a financially strained year), the works by women composers would total a whopping 1.7% of the 12,668 individual performances heard that season. In comparison, works by Beethoven alone accounted for 6.8% of all of the compositions heard (a total of 872 scheduled performances).

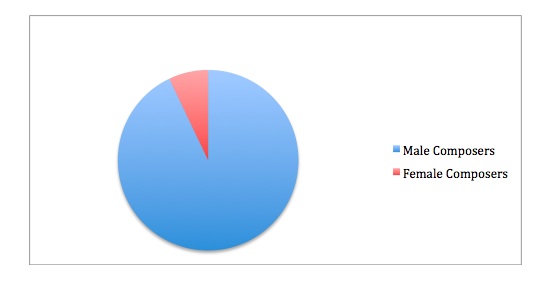

Of the reported 821 composers whose works were performed, there were a total of 58 women composers heard – 7%. Of those, only five women were born before 1920: Amy Beach, Lili Boulanger, Cecile Chaminade, Fanny Mendelssohn, and Germaine Tailleferre.

Though the LAO doesn’t collect specific statistical information about the conductors, we need to recognize that it is the conductors and artistic directors who decide on programming, who have the final say in when and how a composition will be heard. During this past season 73 conductors lead works by women, with an award going to William Eddins who conducted six works by women composers – the most of all the conductors included in the report.

Regarding ensembles, there was a three-way tie for the orchestra that performed the most diverse repertoire when considering the gender of composers – The Phoenix Symphony, Berkeley Symphony and American Composers Orchestra each performed five works by women. However, I should also recognize that The Phoenix Symphony performed five works by Jennifer Higdon, whereas the Berkeley Symphony included works by Lili Boulanger and Germaine Tailleferre, along with more contemporary compositions. It is also important to recognize that of the 67 orchestras that performed works by women, 8 were affiliated with a particular university/college, and 3 were “youth” orchestras.

The most performed work by a woman was Jennifer Higdon’s Concerto, Percussion with 11 scheduled performances. It is notable that Colin Currie was the soloist with four of the five ensembles that played the work. Runners-up were Higdon’s Concerto, Violin, the Pultizer Prize winning piece, which was premiered by and written for Hilary Hahn, who also performed the work 6 times this concert season. Gabriela Lena Frank’s work Illapa: Tone Poem for Flute and Orchestra was also heard 6 times, and featured Jessica Warren-Acosta on Andean flutes in each performance.

Making a direct comparison to the prior season isn’t particularly fair, especially in considering the dramatic drop not only in reporting orchestras but also of pieces and concerts performed. However, it is notable that some trends continue. The career success of Jennifer Higdon and Joan Tower is certainly something to be celebrated – they continue to be recognized on the list of the most frequently performed American composers. Jennifer Higdon was ranked at #7 (between #6 – John Adams, and #8 – Leroy Anderson) and Joan Tower is tied for #16 with Christopher Rouse. On the list of “Top twenty most frequently performed living American composers”, joining Higdon (#2, with 49 scheduled performances) and Tower (tied with Rouse at #9 with 19 scheduled performances) are Gabriela Lena Frank (tied at #13 with Michael Torke with 12 scheduled performances) and Augusta Read Thomas (tied at #18 with Petere Schickele and George Theophilus Walker with 6 scheduled performances).

But it is important to also recognize that this is the inverse of the trends of male composers, the most popular of which are long since dead and buried. In order for a woman’s work to be heard, she almost always needs to personally advocate for the performance. This makes advocating for the works of historical women composers all the more relevant – as is evident from the data, their music won’t be heard unless someone makes the effort to have it performed.

Progress is being made, even during the difficult economic times that we currently face (and their) ramifications on arts funding and patronage. But, perhaps now is the perfect time to reevaluate the status quo and inspire change in programming. As I’ve said before – I am in no way suggesting that we disregard the greatest works in the Western Canon. But can’t we also include the works of women composers, acknowledging their musical history, which more often than not includes their struggle for the opportunity to pursue their interest and work against all odds?