By Sarah Baer

We recently published our Repertoire Report for the coming concert season – you can read the full piece here. The unsurprising truth is that top tier organizations are actively working backwards – regressing – in terms of equitable programming, with many ensembles performing fewer works by women in the coming season than they did in the previous season.

However, we also acknowledge that the systems of white supremacy and patriarchy impact beyond the number of works on any given concert by women composers, and are inherent in the larger infrastructure of the classical music community. That’s why we use this data every year to also look at the conductors who are currently leading ensembles, whether as a primary, assistant, or guest leader. The lack of equity in conducting opportunities has been well documented since before Marin Alsop made history when she was appointed as the Artistic Director and Conductor for the Baltimore Symphony. As more women and BIPOC individuals step into these roles, particularly in elite institutions, there is more potential for the necessary systemic changes to actually take place.

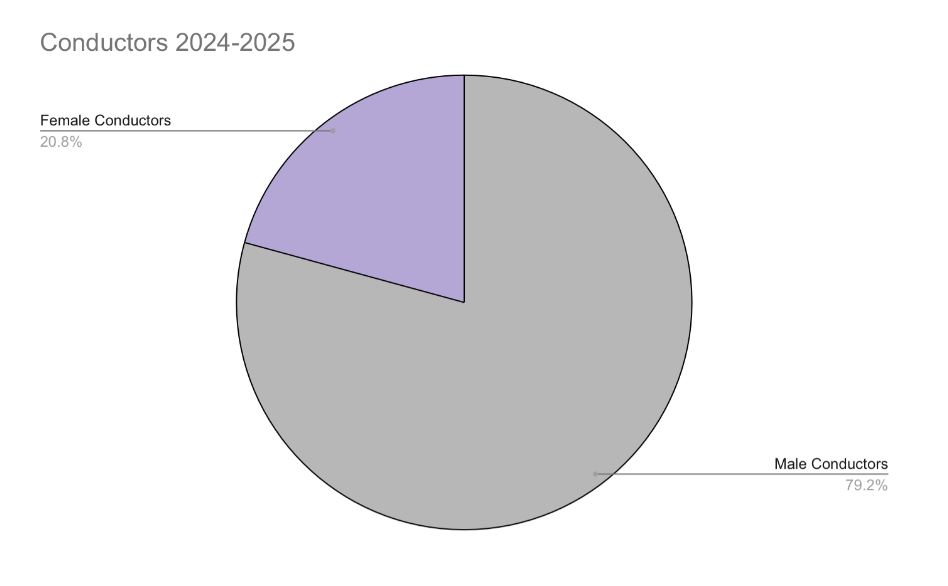

In looking at the data from the top 21 orchestras in the United States (by budget; see the list of orchestras and their music directors at the bottom of this article) for the 2024-2025 concert season, 159 separate conductors will lead at least one concert. Of those, 33 are women. This is the exact percentage (20.8%) of women conductors that we saw in the 2023-2024 season.

This stagnant number of women who have a place at the proverbial table is, like the lack of progress of repertoire by women composers in the programming, disheartening (to say the least).

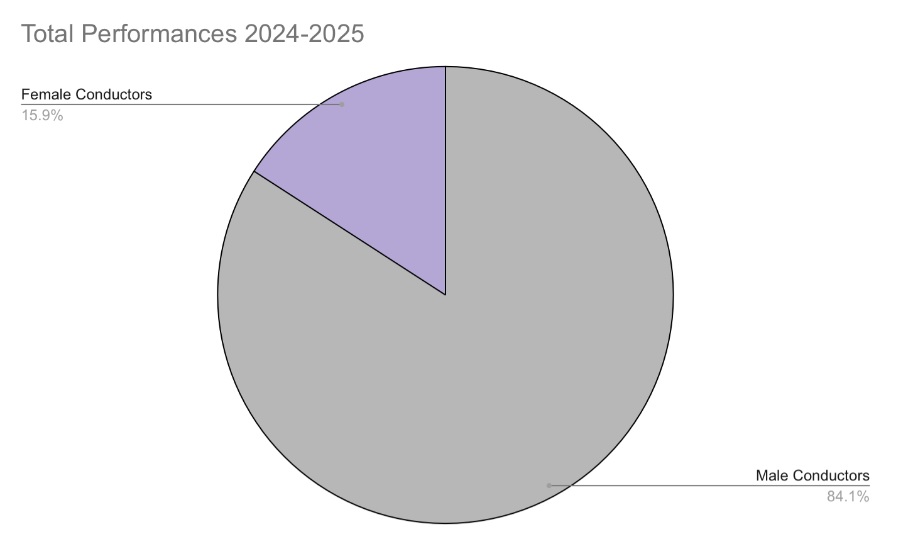

Those 33 women will conduct a total of 230 works, which is roughly 16% of the overall number of performances throughout the season (so these women will conduct a proportionally smaller number of works than the men). As I mentioned in the Repertoire Report, establishing a true equivalency in works conducted/performed is quite difficult. A single work could mean the Overture to Tannhäuser or the entire opera; the difference between minutes versus several hours. There is not yet a way to consider these differences effectively, especially when newly composed works are included.

When considering specifically the performances by these 159 conductors of works composed by women, a total of 69 (which makes up 43%) conducted at least one work by a woman. Marin Alsop conducted the most works by women, a total of seven. Thomas Søndergård, Manfred Honeck, and Gustavo Dudamel all tied for second place with six.

There were also some notable figures who will not conduct any works composed by women in the coming season. These include: Bernard Labadie, Dame Jane Glover, Herbert Blomstedt, Jaap van Zweden, Michael Tilson Thomas, Ricardo Muti, Roderick Cox, and Donald Runnicles. Others, like Nathalie Stutzmann, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Franz Walser-Möst, and Matthias Pintscher, will conduct only one.

Some significant inroads in wider representation for women and BIPOC conductors have been made in recent years, particularly when it concerns these top tier ensembles. For those of us who remember the outcry that was heard throughout the classical music world when Marin Alsop was first appointed in Baltimore, the appearance of more diverse faces wielding batons is a very welcome sight. But the slow progress suggests that systemic issues are still bogging us down. There is still only one woman appointed among these top ensembles (Nathalie Stutzmann), but with Jonathon Heyward and Rafael Payare there are now two BIPOC individuals disrupting the long and stodgy history of European men that typically fill the roster (the preference for European-born men over US-born men conductors is another long-standing issue).

It is all too easy to congratulate and praise ensembles for the smallest amount of progress towards equity that they demonstrate – after all, we love to be optimistic and upbeat. But the truth is, it is these ensembles – the ones with the highest budgets and resources – that could easily spearhead change. They are simply choosing not to.

The excuses vary by ensemble or spokesperson, and they are numerous. They also typically fall into the category of “But, Tradition!” In other words: “But, Systemic White Supremacy and Patriarchy is how we’ve always functioned.” There is no greatness in a tradition that deliberately praises the work of a handful of white men while ignoring – we might say ghosting, pretending that it doesn’t even exist – the work of any others.

Black feminist scholar bell hooks was clear throughout her prolific writings that the path forward – towards justice, toward equity, towards a true representation of human stories in our history books and culture – should not be in reform, but in revolution. To be clear, she also stated that revolution needs to be centered on love, but a revolution nonetheless. By accepting these tiny gestures towards reshaping these preexisting structures, their attempts of reforming institutions based on systemic white supremacy and patriarchy, we will never achieve the equity that is deserved, needed, and owed to us. To quote Audre Lorde, another monumental Black feminist theorist: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

As more reports come out revealing long standing histories – and cover ups – of sexual assault and harassment in orchestral spaces, university music departments, and private studios, it is clear that things have to change in a radical way in order to move forward with any kind of integrity. The world of classical music is wide and varied – it exists far beyond the works of a handful of dead, white men from the Classical and Romantic periods – and the music that is performed, the musicians that perform it, and the conductors that lead the ensembles should be representative of that fact.

For systemic change to take place, for radical changes that move us away from the status quo to take root, we must demand them. There is no excuse for these orchestras – multi-million dollar organizations — to not be leaders in the changes that are being called for, changes that are needed for classical music performances and ensembles to survive.

The top 21 US orchestras (by budget), listed alphabetically, with their music director.

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra: Nathalie Stutzmann

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra: Jonathon Heyward

Boston Symphony Orchestra: Andris Nelsons

Chicago Symphony Orchestra: Klaus Mäkelä

Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra: Louis Langrée

Cleveland Orchestra: Franz Welser-Möst

Dallas Symphony Orchestra: Fabio Luisi

Detroit Symphony Orchestra: Jader Bignamini

Houston Symphony: Juraj Valčuha

Los Angeles Philharmonic: Gustavo Dudamel

Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra: Ken-David Masur

Minnesota Symphony Orchestra: Thomas Søndergård

National Symphony Orchestra: Gianandrea Noseda

New York Philharmonic: Jaap van Zweden

Philadelphia Orchestra: Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra: Manfred Honeck

San Diego Symphony: Rafael Payare

San Francisco Symphony: Esa-Pekka Salonen

Seattle Symphony: Ludovic Morlot

St. Louis Symphony: Stéphane Denève

Utah Symphony: Thierry Fischer