Saturday, June 24, is the 101st birthday of American composer and music educator Ruth Shaw Wylie (1916-1989).

Saturday, June 24, is the 101st birthday of American composer and music educator Ruth Shaw Wylie (1916-1989).

Born in Ohio, Wylie grew up in Detroit and considered herself to be, “a fairly typical Midwestern composer”. After earning her PhD in composition at Eastman School of Music she taught composition and music theory at the University of Missouri from 1943-1949, returning to her undergraduate alma mater, Wayne State University in Michigan, where she taught for another 20 years. She was a pupil of Howard Hanson, Arthur Honeggar, Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, and Bernard Rogers.

Throughout her composing career she explored small and large genres, writing ballets, orchestral works, chamber music, choral works, as well as pieces for voice and piano. Unfortunately, few of her works have been recorded – and those have only occurred in recent years. Though many of her works have yet to be published, all of Wylie’s manuscripts, including working drafts, master sheets, and performance scores of virtually all of her compositions, are held by California State University. (Finding Aid is available here.)

Musicologist Deborah Hayes, who knew the composer personally, has written Wylie’s biography, which is available through Amazon. You can also learn more in an article Hayes has published in the Journal for the International Alliance for Women in Music in which she discusses not only Wylie’s works and career, but the challenges so often faced in writing about women in music. For example, Hayes had difficulty finding information about Wylie’s early years, a point which was pointed out in some peer reviews of her original manuscript:

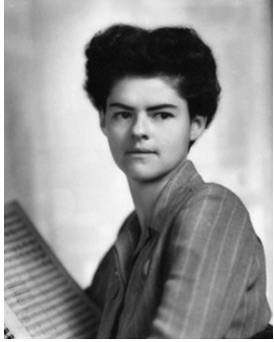

These readers pointed out that, because details of Wylie’s earlier career were missing, my manuscript depicted a composer whose career was unremarkable until she retired and reached the wilds of Colorado, where it blossomed! As unlikely as that story seemed, it was all I had, and her nephew to send me a photo or two through the Estes Park house (bequeathed to him by his aunt) for something suitable. Imagine my surprise when, a few weeks later he reported finding “behind the furnace” several boxes of programs, press clippings, unpublished essays, photos, and correspondence, collected since the 1930s!

Those of us who have worked on historic women composers, and longed for such a find of boxes of materials and manuscripts hidden away, can imagine the thrill of such a discovery – as well as the disappointment that such valuable material was neglected, even discarded, to begin with! Be sure to read the full article here.

Hayes has these insights in describing Wylie’s works:

Like many of her contemporaries, Wylie found her initial inspiration in the and Stravinsky. Through the 1940s and American neoclassicism in their sectional forms, linear procedures, and classical titles. Searching for her own compositional voice, she explored chromatic harmony and expanded tonality, and devised what she called “planal” writing, combining planal (parallel) intervals to create distinctive harmony and counterpoint. “Consonance-dissonance values of each large sonority, as well as each smaller sonority within the individual planes, can be clearly discerned and controlled.” She also sought ways to achieve rhythmic freedom and invention. In a 1946 paper, she wrote that rhythmic concepts found principally in Gregorian chant, isorhythmic motets of the fourteenth century, and the asym- metrical prose rhythms of the sixteenth in freeing music from the tyrannical nine- teenth-century bar line and in devoting a more tender care to the agogic accent in relation to the dynamic stress accent.”

Few of her works have been recorded – but have a listen to two pieces via Spotify below: