Louise Farrenc.

Early Life

Louise Farrenc was born “Jeanne-Louise Dumont” in 1804 in Paris on May 31, 1804. Having come from a long line of visual artists, and growing up in an arts district, Farrenc – much like her brother – was encouraged first by her family and later by her husband to pursue the arts. She got to spend her life doing the things that she loved, and she was lucky; this was unfortunately not the case for many other women during this time (In fact, Farrenc would often later be praised by critics for being “not like other women”). As a child, she received training and eventually became very adept in drawing and painting. She may have even considered a career in the visual arts like her ancestors before her were it not for her childhood piano teacher Anne-Élisabeth Cécile Soria, who helped her discover her love for piano. It soon became evident to everyone around ten-year-old Louise that she harbored incredible talent and passion for music.

Marriage

Within the next decade, Louise met flute player Aristide Farrenc and they quickly became good friends, playing duets together for their communities on their respective instruments. In 1821, a few months after Louise’s 17th birthday, they were wed. Despite getting married at such a young age (at least by present-day standards), theirs was a mature and mutually beneficial union, and Aristide encouraged Louise’s dreams right from the start. Aristide experienced little success as a composer and turned his focus toward music publication, where he built up an incredible reputation for editing and engraving and eventually began his own publishing business.

1835 portrait of Louise Farrenc by Luigi Rubio

Aristide Farrenc

Career

Along with her lifelong dedication to performing, teaching, editing, and composing, the success of Aristide’s publishing business allowed stability for the couple: their daughter Victorine was born in 1826. To get an idea of the societal attitudes that women musicians in the 19th-century faced, one can look at the following back-handed compliment by Antoine Elwart, a contemporary of Farrenc’s and fellow composer:

“[Her vocal samplings] place her well above the majority of those women composers whose shabby and ungraceful melodies make one deplore the lack of technical skill in just about everything that issues from their overly-prolix pens…”

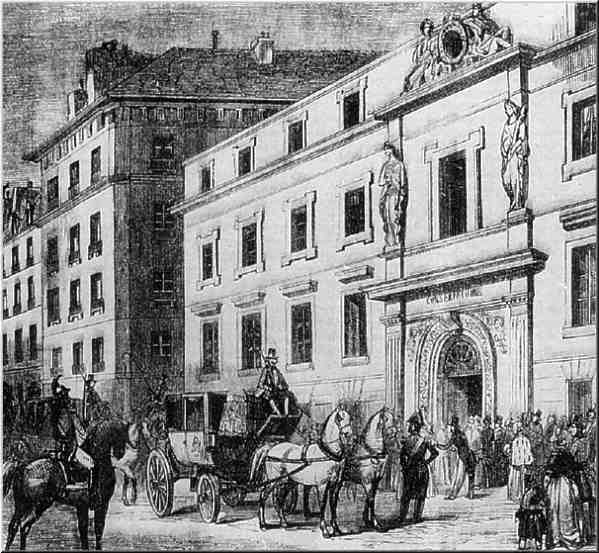

Hired by the conservatoire in 1842, she was the first woman to ever hold a full-time position as a member of the faculty in the Instrumental department. She joined the conservatoire at the same time as a man by the name of Henri Herz. Despite their job roles being equal, their prior experiences having been the same, and having had similar reputations; Herz was paid an annual salary of 1200 francs–200 more than Farrenc’s own salary! To make matters worse, the press mistakenly put out a statement advertising Farrenc’s position as an “professeur supplémentaire” (adjunct professor) rather than her actual, full-time position. For years, she would continue to be paid 1000 francs per annum while other faculty who subsequently joined after would be paid more.

In 1850 she began the appeal to raise her own salary to match that of her male colleagues. Dismayed by the fact that she continued to be paid less than the people around her, she wrote a letter to the director of the conservatoire requesting a raise. He responded that it would be granted to her once funds became available, but the promise wasn’t acted on until she wrote a second letter. The appeal finally worked and her salary was thus raised to match the 1200-franc salary of Henri Herz. She was emboldened to the task because of the massively successful debut of her Nonet a few months earlier.

The Conservatoire de Paris (1860), as Farrenc would have known it.

Middle Years

In 1826, the Farrenc’s had a daughter: Victorine Louise Farrenc. For the next three decades the small family-of-three would each become renowned for their own contributions to the music world; Victorine herself grew into an incredible pianist and composer. In 1859, however, tragedy struck the Farrenc family and Victorine passed away at thirty-three years of age after a long and painful battle with a mysterious illness. In her grief, Louise lost all capacity for creative energy and took a multi-year hiatus from putting on concerts and performing. She would never compose again. Instead, she focused all of her energy on her teaching position at the Conservatoire de Paris and continued with the lessons that she had been giving for years.

Later Life

Louise survived Aristide by almost a decade. In her later years, she maintained an ongoing, multi-volume anthology of piano music that was released to subscribers on a biannual basis– a project that was started in 1861 by her husband to help preserve some of the older music that had gone out of style. This cause was important to both of them, evident

in the fact that they had spent multiple years planning and collecting repertoire in order to begin. Farrenc’s involvement in the anthology–called Le Trésor des pianistes–continued until her retirement in 1873.

Death

She died in 1875 at the age of seventy-one, and was buried at the Dumont-Farrenc family grave in Montparnasse. To her contemporaries, her legacy was unmistakable. Obituary articles in the press lauded the lasting impact of the work she had spent a lifetime on, and her numerous students over the years would go on to make their own important contributions to music.