The recent international conference “American Women Composer-Pianists” named Amy Beach (1867-1944) and Teresa Carreño (1853-1917) as focal points, in celebration of the notable anniversaries connected with them (the 150th anniversary of Beach’s birth, and the 100th anniversary of Carreño’s death). But the conference expanded to cover a wide range of other composer-pianists, including the British — Arabella Goddard, Chilean — Josefina Filomeno, and Mexican — Guadelupe Olmedo.

The conference was a mind-expanding and fascinating two days, and the host – the University Archives of the University of New Hampshire (Durham), together with help from the Music Department — deserve hearty applause for their efforts.

Applause, also, to our intrepid reproter Timothy Diovanni, for attending and providing his insights in this conference report.

We wielded our umbrellas for the damp walk between the Music Building and the Library. A brook scurried underneath our steps. The New Hampshire torrent diminished to a drizzle. Was the drama of the weather a parallel to the excitement of the discoveries of new musical worlds?

“Mrs. Beach belongs to us here at UNH,” Peggy Vagts, professor of flute at the university, touted. She’s right: from the rich source collection in the Dimond Library Archives, to the honorary master’s degree bestowed to the composer-pianist in 1928, and now the exhibition to celebrate her life and achievements, Amy Beach is a symbolic light for the institution to uphold.

As such, there couldn’t be a better place for a Beach conference. (The full program of the two-day event can be seen here.) Leading scholars featured several papers on important themes in the musician’s life. In the session on Beach’s relationship to nature, presenters explored how Beach interpreted her world – especially bird songs — through composition.

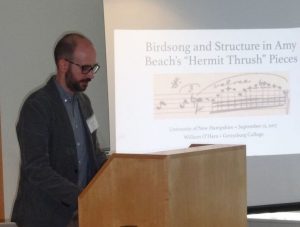

(photo by Anna Kijas)

William O’Hara labeled the process in the “Hermit Thrush” pieces as a simultaneous act of documentation and artistry.

Some papers focused on Beach as a disruptor in the male-dominated realm of music composition.

Sabrina Clarke analyzed how Beach subverted gender conventions in musical form, particularly through her synesthetic key relationships. Beach had synesthesia, meaning that she related certain keys with specific colors.

Susan Borwick exposed how Beach in fact turned the woman subject of Robert Browning’s poem into the object, complete with inherent agency, in her Op. 44 No. 2. Beach did so through omitting the ultimate stanza.

Susan Borwick exposed how Beach in fact turned the woman subject of Robert Browning’s poem into the object, complete with inherent agency, in her Op. 44 No. 2. Beach did so through omitting the ultimate stanza.

Sarah Gerk’s presentation

Sarah Gerk demonstrates that scholarship can be fun! (photo credit Anna Kijas)

Sarah Gerk questioned the romantic conception of male genius to explore how Beach’s genius was treated in textbooks and newspapers. Gerk emphasized how Beach’s favorable circumstances – her social class, her family’s move to Boston, diligent work early in her life – shaped her genius reception.

Hsiang Tu, UNH piano professor, and Jenni Cook, soprano and UNH music department chair after their performance of the Four Songs (Op. 14) (photo credit: T. Diovanni)

Lecture-Recitals complemented paper readings; they provided new insights from the performers’ perspectives. Friday night, several faculty members of UNH performed a concert of some of the smaller-scale works by Beach, such as her Four Songs (Op. 14) and A Hermit Thrush at Morn (Op. 28 No. 2).

To correlate the importance of scholarship with performance practice, the concert included a spoken tribute to Adrienne Fried Block, the foremost Amy Beach scholar, whose book, Amy Beach. Passionate Victorian: The Life and Work of an American Composer 1867-1944, has functioned as a vital resource. Jennifer C.H.J. Wilson, who worked with Block on The Gotham Project and presented on Beach’s “Morning Glories” (Op. 97 no. 1) in the conference, explained how Block acted as a positive role model for her academic career. Block passed away in 2009, and more tributes to her are here.

After the concert, Peggy Vagts’ CD, Persistence: Works by Women, 1850-1950: Music for Flute and Piano was available for purchase. It includes Beach’s Romance (Op. 23) which Vagts transcribed for flute and included in the evening’s performance. The CD’s title demonstrates the perseverance which women composers like Beach exuded in order to achieve success.

(photo credit: T. Diovanni)

Artifacts from Beach’s life in the newly-opened exhibit, “A Brilliant Life: The Musical Career of New Hampshire’s Amy Beach,” provided further context. Viewers walk through Beach’s life, from her childhood as Amy Marcy Cheney in Henniker NH, to her concert tours throughout Europe. Compelling personal affects, such as Beach’s notation books and her portable silent piano keyboard, to practice while on her travels, gave us physical insights into Beach’s experiences.

Teresa Carreño as a child

The other focus of the conference was Teresa Carreño, a Venezuelan virtuoso pianist-composer. Presenters emphasized Carreño’s position as a world-renowned pianist, composer, opera singer, and impresario in the late-19th century. She performed in five of the seven continents, a remarkable feat considering transportation means at the time.

Carreño’s reception was shaped by her gender and ethnicity, as demonstrated in press reactions. Laura Pita illustrated how critics focused on Carreño’s God-given talents. She was considered a vessel of divinity, serious at the piano, boisterous and child-like away from it. Pita argued that this rhetoric ignored the actual work that Carreño completed to obtain her skills (She trained with an intensive, four-hours-a-day schedule starting as a small child.)

Anna Kijas

Scholarly research on Carreño has been hampered by the diaspora of relevant primary sources. Because of recent database compilations by Anna Kijas, accessibility to Carreño documents will dramatically increase.

Much of the same phenomena that affected Carreño influenced other Latin American women pianist/composers of the period. José Manuel Izquierdo constructed the life of Josefina Filomeno, who, although received positively in newspapers, did not enjoy the same success as Carreño. Izquierdo attributed her alleged “failure” to her transition from child prodigy to grown-up artist — a transformation that diminished her appeal as an “exotic and erotic object.”

Alejandro Barrañón (photo credit: Anna Kijas)

Alejandro Barrañón introduced the Mexican composer Guadalupe Olmedo (1856-1889). Barrañón explained that Mexican composers like Olmedo tended to eschew European forms, like the sonata and symphony. Instead they forged their own paths to create a unique Mexican sound, “a process of national identity.” Barrañón gave a brilliant performance of Olmedo’s works that he unearthed in the National Conservatory of Mexico’s special collections. In one case he had to construct part of a piano transcription by using the orchestral version of the same piece that he discovered there. In effect, he was a mystery detective — a sleuth for forgotten music.

Peggy Vagts, flute; Babette Hierholzer, piano; Robert Osborne, bass-baritone; Anna Tonna, mezzo-soprano (photo by T. Diovanni)

To conclude the conference, four musicians presented a dramatized portrayal of musical scenes from Carreño’s life. The program began with her visit (as a nine-year-old child prodigy) to Abraham Lincoln in 1863. The pianist Babette Hierholzer read from Carreño’s memoir – which painted her as fiery and determined – and then performed “Listen to the Mocking Bird,” which Carreño played at her meeting with Lincoln.

(photo by Anna Kijas)

The program proceeded in a similar manner, with works that Carreño performed or composed as well as music by her teachers and mentors (Rubinstein, Rossini, and Gounod). Carreño’s own words and her critic’s responses functioned as spoken interludes between the numbers. They provided an engaging total picture of Carreño’s personality and experiences.

As I look back at the conference, the word tenacity buzzes in my ears. The women pianist-composers featured this weekend experienced invariable prejudices due to their gender as well as (in some cases) ethnicity. Yet, they overcame these obstacles to establish their lives as artists. As Izquierdo’s presentation illustrated, the process was undoubtedly risky: not every performer composer had the same recognition and success as Beach and Carreño. It is therefore with an informed eye that we are astounded by their accomplishments, magnetized by a love for their music and music-making. Nevertheless, they persisted – and now it is our responsibility to tell their stories.

The exhibit at the University Museum, “A Brilliant Life: The Musical Career of New Hampshire’s Amy Beach” continues through Dec. 1 and is worth a trip in itself, or pair it with one (or several!) of the upcoming concerts featuring Beach’s music at the campus. Info on the exhibit is here, Beach events on the campus are listed here, with more details here.

Press coverage of the conference is here (NYTimes) , here (Concord Monitor), and here (NHPR).